Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

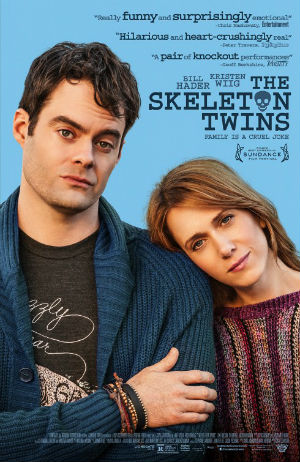

The Skeleton Twins (2014)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The ending doesn’t quite work, does it? Too bad, because everything else does.

Craig Johnson’s “The Skeleton Twins” is a serious-sweet movie, a movie in which, as Jon Stewart said on “The Daily Show,” the humor is organic to the situation. It stars two SNL alums, Kristen Wiig and Bill Hader, but they’re not doing bits. They’re playing complex characters. Particularly him. Hader’s a revelation here. He’s the real deal.

| Written by | Mark Heymn Craig johnson |

| Directed by | Craig Johnson |

| Starring | Kristin Wiig Bill Hader Luke Wilson Ty Burrell |

Hader and Wiig have such good rapport here, and their characters, Milo and Maggie, estranged twins reunited in middle age, know each other so well, that you begin to wonder why they became estranged in the first place. The movie wonders it, too. “How did we go 10 years without talking?” Maggie says at one point. Milo mumbles a reply, and she, oh right, remembers, and they fumble their way back to a kind of rapport until the thing emerges again.But it’s not just the thing: it’s them. They get along because they know each other so well but that’s also what splits them up. They know where to cut.

Jesus, Maggie

Suicide permeates the film. Long ago, their father, seen only in flashback in Halloween mask, killed himself, while the movie opens with a double suicide attempt: Milo slits his wrists in a bathtub while Maggie stares at a handful of pills at the bathroom sink. That’s where she gets word of Milo’s attempt. So she flies to L.A., visits him at his bedside. He calls himself a gay cliché and asks her to leave. She asks him to come back to New York. Upstate somewhere. She lives in a nice house with a nice man, Lance (Luke Wilson), and they’re trying to have nice kids. In his new room, he picks up a photo of her and Lance hunting. Under his breath: “Jesus, Maggie.”

Everything is in that two-word exclamation. Who is this person that I used to know so well and haven’t seen in 10 years? Who is she trying to be now? Who does she think she is?

At dinner, Lance, a sweet, forthright, unimaginative man with the patience of Job, says that he and Maggie are trying to have kids, and Milo’s response to Maggie, spoken with his fist resting on his cheek, is, “I thought you never wanted to have kids.” Maggie’s confused for a moment. No doubt she said this at one point, but she’s an adult now. Except Milo’s right. She doesn’t want kids. She’s actually taking birth-control pills to make sure she doesn’t get pregnant. She’s also sleeping around and hating herself for it. Later in the film, after she confesses all this to Milo, and tells him—and herself—that Lance is a good man and their relationship is good, this is Milo’s quiet, sympathetic response: “Maybe you don’t like good.”

If Maggie’s problem is too much sex and too little need, Milo’s is the opposite: too little sex and too much need. He slits his wrists because of a bad breakup in L.A., and in New York takes up again with Rich (Ty Burrell), his old English teacher, closeted, who seduced him when he was 15. That, it turns out, was the reason for Milo’s estrangement with Maggie: She saw it as wrong and ratted. He didn’t and resented.

Question: Is he trying to do the same to her here? Did he arrive in New York to break up Maggie and Lance? I didn’t think so watching, and I don’t think so now, but the point can be raised. Maggie raises it herself near the end, during her last big argument with Milo. He’s insinuated the information about the birth-control pills to Lance—Lance is worried he’s firing blanks, and Milo wants to ease his troubled mind—and when Lance confronts Maggie, she tells him, “I’m a sick person.” But she goes off on Milo. And we get this exchange:

Milo: Maybe I should try fucking all my problems away!

Maggie: Well, maybe next time you should cut deeper.

Families.

Someone to laugh at the squares with

What makes the movie work is their rapport, and the humor in their rapport, and even its claustrophobia. When they go out for Halloween, they don’t mingle. “Don’t they know anyone else?” I thought. Gore Vidal called Tennessee Williams, “Someone to laugh at the squares with,” and I guess that’s their relationship. Although they laugh less at the squares than at the absurdity of life and family and upbringing. “Well, at least she’s sending in the light,” he says after their new-age mom returns with a vengeance.

I also liked this aspect of the film: One of the two characters is gay, tragedies abound, but none is really tied to homophobia. Even closeted Rich seems an anachronism. Everyone’s pretty cool with it. It’s a non-issue. We’re onto other issues now.

One of Milo’s issues is his status in the world. He talks about a bully named Justin who used to pick on him in high school. Back then Milo was basically told, prefiguring Dan Savage, “It gets better.” It will get better for him and worse for Justin, because these are Justin’s best days. The universe will eventually make sense. Except Milo went to L.A. and nothing happened. His acting career didn’t take off, his writing career didn’t take off. Plus he’s alone. And one day he looked up Justin online. Justin had a pretty wife and two kids and a steady job. “It turns out I’m the one who peaked in high school,” he tells Maggie. To her credit, Maggie doesn’t try to buck him up. She basically says, “Welcome to the party, pal.” She says the line that should be imprinted on every mirror in every bathroom in the world. A few people are happy, sure, but:

The rest of us are just walking around, trying not to be disappointed with the way our lives turned out.

I was ready to say a hallelujah at this point. But then we got the ending.

After the birth-control revelations, and the “cut deeper” remark, Lance and Maggie break up, Milo leaves town, and Maggie goes to the scuba-diving center where she’s been sleeping with the instructor and hating herself for it. He’s not there. She’s alone. And attaches weights to the equipment. Suicide, as I said, permeates “The Skeleton Twins”: it begins with a suicide attempt and it ends with a suicide attempt. After she sinks to the bottom, she begins to struggle. She wants to live. But she’s done her job too well and can’t get free. And then suddenly Milo is there, freeing her, and they both ascend to the surface. For a moment I thought it was a dream. But it’s not. It’s the type of serendipitous rescue I didn’t expect in a serious movie. Call it a straight cliché. The man to the rescue. “Really?” I thought. “Really?” What would Milo make of this ending? He would have a cutting remark for it.

I’m glad he returned, though, I just wish it had been in less-dramatic fashion. There’s a line in Syd Straw’s song, “CBGBs”: “Abandonment like that was easier then.” When you’re young, friends are easy to be had—every school year, you’re tossed in with a new group—and that’s why abandonment is easy. But then you age, and opportunities narrow, and people drift. So you need to hold onto the people you have. Because we all still need someone to laugh at the squares with.

—September 29, 2014

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard