Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

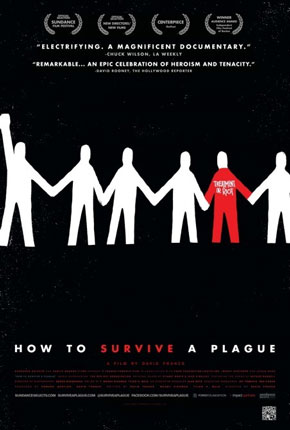

How to Survive a Plague (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

At first you think it’s Dan Savage even though you know it can’t be Dan Savage. He’s too young for this time period and since when did Dan live in Greenwich Village? But there he is. That’s gotta be him, right? No. It’s not him. Dude turns out to be Peter Staley, who went from being a closeted Wall Street broker in 1987—with a homophobic mentor who tells him fags get what they deserve for taking it up the ass—to an AIDS activist and member of ACT-UP, who in 1988 argues with Pat Buchanan on CNN’s “Crossfire” about access to AIDS drugs. Pat Buchanan winds up agreeing with him.

Then there’s the other dude, Bob Rafsky, the PR exec with a young daughter, and an ex-wife he calls the greatest romance of his life, even though, you know, he’s gay, and out now. He came out at 40. We see him in the low-def video of the day, a T-shirt-wearing activist who seems more serious than the noisy folks around him. His every word, his every action, says: This ain’t no party, this ain’t no disco, this ain’t no foolin’ around. It’s as if his life depends upon the outcome.

How about that third dude, the snob, the one with the nose almost literally in the air, who can’t make an internal PSA without lighting a cigarette and taking a deep drag on it? Mark Harrington. Of whom Larry Kramer, a talking head in the doc, says, “Right away Mark digested [the scientific literature] as if by osmosis and within a few weeks he had come up with a glossary of AIDS treatment terms.”

Kramer, famously pugnacious and controversial, is one of the first talking heads we see in “How to Survive a Plague.” We also see a few scientists and doctors, and a few other activists. But slowly it dawns on us who we’re not seeing: Mark Harrington, Bob Rafsky, and Peter Staley.

That’s the tension for the viewer in David France’s documentary. In this way it’s as suspenseful as any war movie. We’re worried about the characters on the screen. We’re worried about who lives up to the film’s title. We’re worried about who lives.

And you behave like this

“How to Survive a Plague” is less about the AIDS crisis than it is about the gay community’s reaction to governmental indifference to the AIDS crisis. The Reagan and Bush administrations ignored and played down. The gay community acted up.

The doc reminded me of my own indifference to the direct actions of ACT-UP back then. I remember watching on the news (ABC World News Tonight, kids) one of ACT-UP’s protests outside of NIH or FDA headquarters, in some Maryland suburb of Washington, D.C., and thinking, What are these people protesting? That cures don’t exist? I thought it was silly. I seem to remember conversations with smarter friends that went something like this:

She: No, they’re protesting that the FDA isn’t releasing AIDS drugs.

Me: Which don’t exist.

She: They exist. You can get them in Canada.

Me: Really? Canada has a cure for AIDS? I’m surprised we haven’t heard about that.

She: They have drugs that help some people slow down the disease. But the FDA won’t release them.

Me: I assume because they’re not safe.

She: Safe? When the alternative is dying?

That was the early struggle that “Plague” documents. How do you get the drugs? Why were drugs available in Canada but unavailable in the U.S.? Didn’t anyone care?

The U.S. government certainly didn’t. One wonders all over again what would’ve happened if the AIDS crisis had exploded during a more sympathetic time with a more sympathetic administration. “We are in the middle of a fucking plague!” Larry Kramer shouts during an internecine battle between ACT-UP and its offshoot organization, TAG (Treatment Action Group). “And you behave like this!” His words could just as easily have been directed at the Reagan and Bush administrations. At Jesse Helms. At me.

This schmuck behind a curtain

The doc starts in 1987, Year 6 of the crisis, and updates us annually on worldwide AIDS deaths: from 50,000 in 1987 to nearly 10 million in 1996. But they’re just numbers. We’re interested in the people.

There’s Staley getting arrested outside NIH headquarters. There he is giving a big speech in San Francisco to scientists and researchers. He’s putting a human face on the disease.

There’s Rafsky in 1992 confronting then-candidate Bill Clinton during the U.S. presidential campaign. He shouts, “What are you going to do about AIDS? We're dying!” Clinton strikes back. At the next ACT-UP meeting, hands in the air, Rafsky admits a kind of defeat. “Never get into an argument with a Rhodes scholar,” he says. But their exchange made headlines. It brought AIDS back into the headlines. For a day.

Their protests and their speeches bring movement. The scientists agree. A direct action in Bethesda gets the FDA panel to change its mind and approve the drug DHPG. Harrington is nonplussed. Off camera, he says something that reminds me of what Deep Throat said about the White House in “All the President’s Men”: these aren’t very bright guys, and things got out of hand:

It was really an amazing encounter, but it sort of felt like reaching the Wizard of Oz. Like you’ve got to the center of the whole system, and there’s just this schmuck behind a curtain.

It’s no surprise that things diverge. Direct actions only do so much. Too many voices invariably dilute the message. Not enough people of color on the FDA panel? Really? Who do you want on there and how smart are they? Because meanwhile people are dying.

The internecine battle between ACT-UP and TAG, unfortunately, takes place off-camera, and, save for Larry Kramer’s outburst, in sotto voce. It feels almost swept under the rug. Afterwards, we lose track of the TAG fellows and get a bit too much of Bob Rafsky. That’s awful to say. He dies in 1993, ’94. He has an extended monologue at the funeral of another AIDS activist that goes on too long. That’s awful to say, too.

Then TAG asks the FDA not to approve drugs too quickly? Isn’t that the opposite of their original message? There’s a sense of floundering. There’s a sense that every early victory was counterproductive. “1993 to ’95 were the worst years,” says David Barr, ACT-UP’s lawyer. “It was a really terrifying time. Then we got lucky.”

It happened in 1996. Oddly, I don’t remember the news. Maybe I was confused by it. Maybe I thought it was like AZT and simply delayed the inevitable. But the triple drug therapy that scientists came up with saved millions of lives. Including….

Life during wartime

It’s at this point that David France gives us, one after the other, silent at first, the rest of the talking heads: Staley and Harrington and Barr and Jim Eigo and others. They lived. It’s a glorious moment but there’s no real celebration in it. Staley, whose first words in the doc were, “I’m going to die from this,” now has survivor’s guilt. “Like in any war,” he says, “you wonder why you are here.”

Shouldn’t there be more of a celebration? Shouldn’t there be a party, a disco, some foolin’ around? At a Democracy NOW conference about the doc earlier this year, Staley said the following:

Triple drug therapy in 1996 saved my life. And those therapies came about because the government spent a billion dollars on research, starting in 1989, 1990. And that all came about because of pressure from advocacy. So I’m alive because of that activism. And I hope people will see this film. It’s about how when—it’s about people power being able to actually create change and to change things for the better. It’s not just an AIDS story. Anybody who’s involved in the Occupy movement should run to see this film. Anybody that wants to change the world should run to see this film.

That message is slightly undercut in the doc—if it was even David France’s intention. We don’t get enough about the unbroken line from activism to policy change to cure. That line feels broken here. “How to Survive a Plague” is winning year-end awards but it didn’t blow me away. Once again, as with many of the documentaries I’ve seen this year, I thought: great subject, OK film.

—December 20, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard