Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

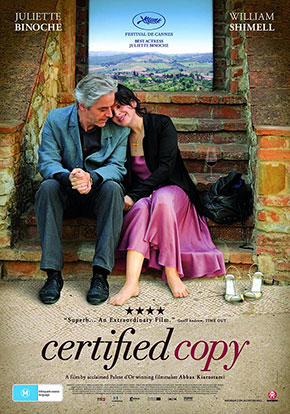

Certified Copy (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

WARNING: SPOILERS

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Certified Copy” is the kind of foreign film that turns on most American movie critics and turns away most American moviegoers. The film is confusing and unknowable, the main characters erudite and insufferable, the settings exotic and confined and possibly nightmarish. It’s the kind of film that requires subterfuge to sell. The U.S. trailer, for example, gives us beautiful shots of Tuscany, and Juliette Binoche in full middle-aged flower, and an implied, heavy romanticism. Then these words appear on the screen:

a writer in search of meaning

an art dealer in search of originality

one day

two strangers will play

a game of seduction

Let’s break down each of these:

a writer in search of meaning

Is British essayist James Miller (William Shimell) really in search of meaning? I thought he just wanted to get out of town. He wants to be in the sun. He’s more like a writer in search of simplicity. He’s tired of the life of the mind and wants to live the life of the moment.

an art dealer in search of originality

This is said of Elle (Juliette Binoche), she of the best middle-aged cleavage I’ve seen in years. But she’s not in search of originality. She’s in search of romance, of connection, just like the women who will see this film. Ultimately they’ll be as disappointed as she.

Finally:

one day

two strangers will play

a game of seduction

This is the biggest lie of all since this is the one game they don’t play. From the start, when you think they are merely strangers (as, indeed, they might be), he is distant and she is testy. There is no flirtation, no exploration, no curiosity. It’s flat. If movies tend to give us the blossoming of love without the prickliness of the relationship, “Certified Copy” gives us the prickliness of the relationship without the blossoming of love.

The movie begins with Miller at a small literary gathering in Tuscany, reading from his latest book, “Certified Copy,” in which he posits that “the copy has value in that it leads us to the original and satisfies its value.” This idea, this theme, is played with immediately. The book itself is a copy, a translation of the original, and is in fact more popular in Italy than the original is in Britain. Miller’s apologetic line as he arrives late, “I would blame the traffic but I walked here,” is a copy, or unintentioned repetition, of the translator’s earlier apologetic line for Miller’s tardiness. Meanwhile, Elle, sitting in the front row with the translator, has to deal with her copy, a teenaged son, who wants to leave and get something to eat.

And we’re just starting.

The next day Miller meets Elle in her antique art shop, walks in circles for several minutes while he waits for her, giving us, over and over, his image, his copy, reflected in the antique mirrors. This will happen with many mirrors, and many windows, throughout the film.

Finally Elle shows up, they get into her car and drive out into the Tuscan countryside. “I can’t believe you’re in my car,” she says, like a groupie, but he remains distant, chin up. He’s not a snob, he’s just ... disinterested. Like a husband hanging with his wife for the five thousandth day. Why put on a show? The two are obviously getting to know each other but without the feel, the spark, of getting to know each other.

In another small Tuscan town, known for its weddings, she takes him to see a work of art, thought to be an original, now known to be a copy, and thus valued less. Should it be valued less? Isn’t it just as valuable as before? He talks about it for a bit, then gets cranky and begs off. One can tell he’s already tired of the subject. Just as we’re tired of him.

Things pick up at a small café when he steps outside to take a phone call. The patron of the place (Gianna Giachetti), a wise woman, assumes he and Elle are husband and wife, and engages Elle in conversation about men in general. Most men sleep in on a Sunday morning, she says. Look at your husband: dressed up, taking you out for coffee. True, he didn’t shave, but… Elle plays along. She even comes up with a not-bad story about how he only shaves every other day, and their wedding happened to fall on a non-shave day, so he didn’t bother simply because it was a non-shave day. When he returns, Elle informs him what’s going on and outside they continue the charade, talking like they are married. She get a phone call—from her son—and afterwards she complains about her son, how he never thinks, and Miller takes the general view that kids live in the moment, which is a good way to live. Her response—“You might be living your life, he might be living his life, but you’re both ruining me!”—sounds like a wife’s response. One of her next responses—“When was the last time the three of us had breakfast together?”—is a wife’s response.

And like that they’re suddenly a couple. Without any of the fun involved with being a couple.

They argue about a statue in the piazza, they argue about wine in a restaurant, they argue over the fact that he fell asleep last night, on the night of their 15th wedding anniversary, as she was preparing herself in the bathroom. She looks at the young couples getting married in the town with nostalgic eyes. Oh, to be young and in love again. There’s a nice moment, in the restaurant, when she’s waving through a window at newlyweds she’d met earlier. They try to talk through the window but none can hear the other. As if a distance of 15 years, rather than a mere pane of glass, separates them.

So were they a couple before and we just didn’t realize it? In the beginning, when she gets one of his books signed for her son (Adrian Moore), her son, who looks like a mop-topped, French, Elijah Wood, teases her as to why she didn’t bother with his surname. What was she hiding? This sets her off.

Is that what she was hiding? The same surname? The fact that le fils est son fils?

But acclaimed Iranian writer-director Abbas Kiarostami seems to be going for something bigger than cases of mistaken identity or games of seduction. As the day progresses, as evening falls, as he follows her into a church and then into the garret of the hotel where they spent their honeymoon 15 years earlier, and she lounges seductively on the bed (the only real moment of seduction in the film), and then seems to suddenly vanish, leaving only him, and then not him, just bells tolling in the background, one gets a sense of a relationship, or a life, lived in a day. Of life sped up. That sense that we know who we don’t know, and don’t know who we know, and how it all goes so quickly. He’s getting at the very instability of life.

Yet I didn’t like the movie much.

I’m all for instability. But neither character is particularly likeable: She demands too much, he is present too little. They’re not even interesting, in the way that Jake LaMotta, another unlikeable character, is interesting. They’re just annoying.

The film is shot beautifully but I may be growing tired of the old directors’ tricks of obfuscation and directness—of dialogue spoken either off-camera or directly to the camera.

The theme of the validity of copies is interesting but ... how does it relate to the shifting, unsettling relationship between Elle and James? Is Kiarostami playing with the original, the genuine, so that by the end we cannot tell between the genuine and the false, the original and the copy? And if so, is this profound? It feels less profound to me than what I’ve described above: the instability of life.

Overall, there’s just not enough pleasure here. Early in the movie, Miller, defending the simplicity of Elle’s sister, says that the problem with the human race is that we’re the only group of animals “who forgets that the whole purpose of life, the whole meaning... is to have pleasure.”

There are pleasures in “Certified Copy” but not enough for a recommendation.

—May 11, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard