Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

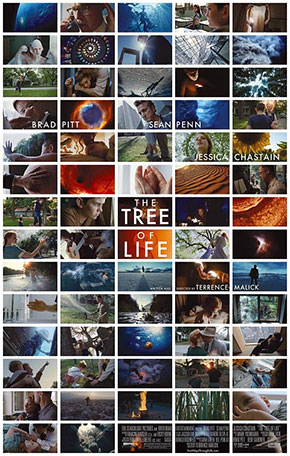

The Tree of Life (2011)

WARNING: NATURAL (RARELY GRACEFUL) SPOILERS

Terrence Malick’s “The Tree of Life,” which is confusing audiences around the world, is essentially an unresolved Oedipal tale in 1950s Waco, Texas, punctuated by frequent Job-like prayers to God, and framed by the beginning and end of time. What’s so difficult to understand?

Of course, for “unresolved Oedipal tale” you could substitute a boy’s internal struggle between the way of nature, which is the way of his father (Brad Pitt), and the way of grace, which is the way of his mother (Jessica Chastain). That’s the true battle. The first words we hear, in fact, in voiceover narration from the mother, set up this dichotomy:

The nuns taught us there were two ways through life: the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you'll follow.

These lines are also in the trailer and I loved them as soon as I heard them. She sets up the dichotomy, gives us one half, nature, and in the audience I thought, “OK, so what’s the negative half?” I’m so used to nature, juxtaposed with the cruddier aspects of modern society, being used as the positive, as the “what we need to return to,” that I assumed the same here. But in the larger scheme of things, which is the only scheme Malick works in, nature is what we are while grace is what we aspire to.

Again, from the mother:

Grace doesn't try to please itself. Accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked. Accepts insults and injuries.

Nature only wants to please itself. Gets others to please it, too. Likes to lord it over them. To have its own way. It finds reasons to be unhappy when all the world is shining around it. And love is smiling through all things.

Malick’s voice-over narration, used extensively in his films, never feels like voice-over narration to me; it’s more an articulation of our most profound feelings. It’s poetry.

The movie’s epigraph is from the Book of Job—another piece of poetry:

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding. Who determined its measurements—surely you know. Or who stretched the line upon it? On what were its bases sunk, or who laid its cornerstone, when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

This is essentially the “Who are you to question Me?” Bible verse and it’s invoked throughout the film, since God is questioned throughout the film, particularly around the issue of death. A boy dies at a neighborhood swimming pool and young Jack (Hunter McCracken), our protagonist for much of the movie, who is trying to sort through everything, and who has already prayed to God to help him be good, asks, “Where were You? You let a boy die.”

More immediately, there is the death of Jack’s younger brother, R.L. (Laramie Eppler) which opens the film, but whose death appears to be set 10 years after the film’s centerpiece. A telegram arrives—one assume a war—and the mother receives it, reads it, sits back stunned, horrified, and then a strangled scream begins to emit from her throat when we cut to the father at the noisy airfield where he works. The way this is directed by Malick and edited by his team of five—not to mention the acting and the sound effects editing—is brilliant. And it eventually leads to this thought, again from the mother, in voiceover: “Lord: Why? Where were you?”

At which point, as if in answer, we cut to the beginning of time.

Some have mocked Malick for his deep perspective, and for showing us the creation of life, both in the universe and on earth, and the movement of life on earth from water to land, but it is the ultimate answer to her and his and our question. Where was God when tragedy struck? That’s what existence is. Life is birth and change and death. He let every dinosaur die and you’re questioning him about R.L.? But that’s the way with us. Only when it hits close to home do we question it. Only when it happens to the good do we question it. Only when it hurts beyond measure. But the argument can be made, and has been made, millennia ago, that it’s the hurt that moves us from the way of nature to the way of grace. Aeschylus:

In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.

Young Jack’s battle is more immediate. We see him from birth to ... age 10? 12? We see him run and strive and pause and figure out. Malick tells his tale unconventionally, through images and metaphor and music. We go from a door opening underwater to the birth to the small foot in the big hand. We go to the ball, and walking with daddy, and running, and iodine on the cut knee. We go to the mother with the butterfly and the animal blocks: the Alligator; the Kangaroo. Jump jump jump. Then we go to the crib by the window and the new baby brother and the look on the boy’s face like “What the hell?”

This is a period dominated by the mother. Malick’s images are so evocative they reminded me of my own, two decades and 2,000 miles further north: frogs and grasshoppers and Halloween; climbing trees and kick-the-can and sparklers; running through yards and rolling down hills. There was a fire—God let that happen, too—from which a neighborhood kid still has the burn marks on the back of his head, where no hair will grow, and it freaks Jack out, this imperfection, and he keeps his distance. It also reminded me of a kid I used to see playing in the Lynnhurst swimming pool in Minneapolis in the late 1960s. He was a burn victim, too, with burns on his back and chest, and it freaked me out, this imperfection, and I kept my distance.

There’s also, amidst all this, the learning of boundaries—the neighbor’s yard, don’t cross this line—lessons imparted by the father. The idyllic period, the mother period, comes to a close, you could say, at the dinner table, when young Jack asks, “Pass the butter, please,” and Jack’s father corrects him, “Pass the butter, please, sir,” then stands up to imaginarily conduct the Brahms they’re listening to.

Now it’s the father who dominates. He’s not a bad man, or a bad father, he’s just the way of nature. He’s trying to teach his boys how to be tough in a tough world. He doesn’t want them to wind up like him, who gave up his calling, music, for regular work, to which he goes to regularly, never missing a day, and comes home dissatisfied and unwanted. He wants his boys to grow but stunts them. At the dinner table, young Jack seems almost deformed, hunched over and twitching, since he doesn’t know what he’s allowed to do, since the boundaries the father is imposing are both necessary and arbitrary, not to mention hypocritical. Elbows off the table. Yet his father keeps his elbows on the table. In the yard, when the father affectionately tries to rub the back of his son’s neck, Jack flinches.

The mother is soft, the father hard. The mother points to the sky and says “That’s where God lives” and the father says “Hit me.” He says, “It takes fierce will to get ahead in this world.” The mother is good, and the boy wants to be like her, and he prays to God to be like her, and the father says, “You want to succeed, you can’t be too good.”

It’s the younger brother, L.T., who rebels first, at the dinner table, telling the father to be quiet, and there’s an eruption, and everyone scatters, and the father is left alone shoveling food into his mouth. At the same time, L.T. is closer to the way of grace. He has the best part of the father, his musical talent, and there’s a scene where he plays guitar on the front steps, and the father listens, proud, that his son has an ear, while Jack stalks the edges and plots. As the father dominates Jack, Jack tries to dominate his brother. But L.T. says, “I won’t fight you.” L.T. says, “I trust you.” L.T. paints beautifully and Jack upends water on the painting. As Jack’s relationship with his parents give off whiff of Oedipus, so his relationship with his brother gives off whiffs of Cain.

The entire movie is a montage, impressionistic, one image leading to another, things all of a sudden just happening as they do in the world of kids. They wake up one morning and their father is gone— on a business trip, apparently; around the world, it turns out—and Jack, freed from under his father, becomes more like his father. He becomes more like the way of nature. He and his friends stalk the neighborhood, like extras out of “Lord of the Flies,” throwing rocks at the windows of abandoned garages. Jack has discovered girls at school and now he discovers women in his neighborhood, including his mother, washing her bare feet with the hose. One day he sees a neighbor lady leaving her home and he sneaks inside and looks through her things. He lies her nightgown on the bed. Then he’s running with it, breathlessly, down to the creek, where he hides it, his shame and his desire, under a log. But that’s not good enough. People are passing. So he puts it in the creek and lets the current take it away. Again, I was reminded of my youth, and the perverse way a burgeoning sexuality exhibits itself.

When the father returns, excited by his trips to China and Germany, things get worse. It’s a clash of the ways of nature. Jack sees his father flirting with a waitress, keeping the dollar bill just out of her grasp, and it’s like an earlier scene at school, where Jack had done the same with a pretty girl correcting his paper. He sees his father working under his jacked-up car, and he knows how easy it would be to kick the jack away. He actually looks around to see if anyone is watching. Even his prayers are now the way of nature: “Please, God, kill him. Let him die.” Then his father’s plant closes and his father returns diminished and the family is forced to move. The father calls Jack his sweet boy but Jack says, “I’m as bad as you are. I’m more like you than her.”

This is the brunt of the movie, as I said, with excursions to the beginning of time and into contemporary times, with an adult Jack (Sean Penn), a successful architect, still dealing with the legacy of his father and the death of his brother. We see him lighting a candle to his brother. We see him apologizing by phone to his father. We see him waking up and not talking with his wife. They live in a vertical box of glass and stainless steel and he works in a bigger vertical box of glass and steel, and he designs same, one assumes, and for a time I thought this was a third way, since neither grace or nature is present, but I don’t think that’s where Malick is going. I’m not quite sure where he’s going, to be honest. We get images, dream images, which may be of heaven, or the end of time, or death. When Jack was born he floated through an underwater door and here he walks through a door in the desert so death can be assumed. He winds up on the beach—that point where life began—and we get reunion and reconciliation and forgiveness: the adult Jack with his father and mother; with the young L.T. and with his younger self. We get a sense of welcome and forgiveness and grace. Then we see the adult Jack, back in his office, smiling. We see a skyscraper of glass and steel and all that represents. We see a long extension bridge and all that represents. We see the flickering flame image we’ve seen throughout the movie. Is it God? Is it akin to Kubrick’s monolith? Whatever it is, it’s the last image we see in the movie.

So. The obvious question: What does this unremarkable Waco, Texas, family have to do with the beginning and end of time? The obvious answer: as much as anyone.

Another obvious question: How much of the Waco period is Malick’s own childhood? It feels very memoirish. One can even imagine the movie simply being the Waco period, with more conventional voiceover narration (from the adult Jack) and more conventional scene presentation. But that would not be a Malick movie; and it would be a lesser movie.

There are few movies as ambitious and beautiful as “The Tree of Life.” It doesn’t all work for me, but, where it does work, it works on a level few works of art, let alone movies, reach.

—August 15, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard