Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

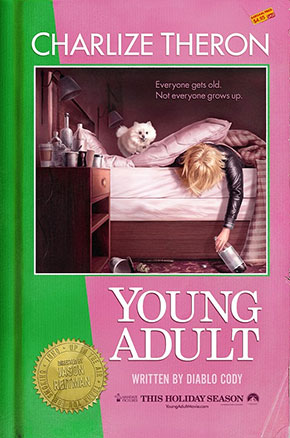

Young Adult (2011)

SPOILERS: HERE I COME

Mavis Gary is one of the most original characters American cinema has produced in years and Charlize Theron totally embodies her. So where’s the buzz? The film, and Theron, had caché among critics last summer but landed with hardly a noise in December. Maybe Paramount pushed it poorly; “Young Adult” has never appeared in more than a thousand theaters. Maybe critics haven’t shouted loudly enough. Some of them seem put off by the film’s dark humor, too. Is the audience as well? When Patricia, Paige and I saw the movie in a small, downtown Seattle theater with two dozen other people, I got the feeling we were the only ones laughing.

But man were we laughing.

The Concept

A writer of a series of young adult novels centering around the solipsistic machinations of high school girls, Mavis lives in a high-rise condo overlooking the Mississippi river in downtown Minneapolis. Nights are for drinking (and one-night stands), mornings are for hangovers (and regret), afternoons are for coffee with friends, or cadging bits of overheard dialogue from teenage girls—such as the Office Depot clerk who mentions her “textual chemistry” with a boy, which Mavis then includes in her next book.

But the routine is getting old, a new “Waverly Place” book is due, and after staring at the blank page of “Chapter One” in her computer she distracts herself with email. Along with the usual spam and Facebook crap, there’s a message, “Look who’s arrived!,” with a picture of the new baby of Buddy Slade (Patrick Wilson), Mavis’ high school boyfriend, who still lives in her hometown of Mercury, Minn. And it dawns on Mavis: this is the solution to her misery. Not to have a baby of her own but to win Buddy back. She’s 37 but it’s as if she’s still involved in the machinations of high school girls. It’s as if she never grew up.

That’s the film’s tagline, by the way: “Everyone gets old. Not everyone grows up.” Why doesn’t Mavis?

When We Grow Up

You can blame what she calls “Y.A.,” the young-adult novels she’s been writing for ... 10 years? Fifteen years? They’ve stunted her. Her imaginative world has never left high school.

You can blame her beauty, which is otherworldly (this is Charlize Theron, after all), and which, even at 37, allows her to get away with shit mere mortals can’t. “Guys like me are born loving women like you,” says Matt Freehauf (Patton Oswalt), one of the guys she ignored in high school, when she returns to Mercury. It’s not necessarily a compliment. To either one of them.

You can blame alcoholism. More on this later.

Mavis may also be a victim of the American myth of “getting out,” embodied, most notably, in the early songs of Bruce Springsteen: It’s a town full of losers and I’m pulling outta here to win, etc. This is exactly what Mavis did. She saw Mercury as a town full of losers, so she pulled out of there to win. She made it all the way to the big city, to Minneapolis, but discovered another dead end. It’s a familiar story: She escaped Mercury but can’t escape herself. The look of disgust on her face isn’t just for what she sees around her—the sad little malls, the sad little people—but for the sad little person inside her.

She knows this, too, deep down. She’s not dumb. The opposite. “Young Adult” is a movie about delusions, and Mavis’ are whoppers, but she maintains them through her own deeply skewed internal logic. She maintains them because she can argue so well.

When Matt reminds her that Buddy Slade has a wife, she counters, “No, he has a baby. And babies are boring.” When Buddy says he feels like a zombie from all the sleepless, new-baby nights, she seizes upon it. “It’s a pretty strong statement to make,” she tells Matt later. “A zombie is a dead person, Matt.” Finally when she makes her play, and Buddy, astonished, tells her, “I’m a married man,” she responds sweetly, as if they were talking about an addiction, “I know. We can beat this thing together.”

It’s hilarious and awful and delusional, but what she’s offering is actually enticing— and not just because Charlize Theron is offering it. Family means responsibility, which means roots, which means being stuck in one spot for the rest of your life. It’s a trade-off everyone makes. Mavis is offering Buddy what age and responsibility tend to restrict: possibility and freedom.

It’s a Shame About Mavis

Even so, every one of her scenes with Buddy is excruciating. During her road trip to Mercury, she rewinds the same ancient mixed tape, the one that reads MAD LOVE, BUDDY on the spine, so she can listen, over and over, to “The Concept,” an awful, early-’90s college-radio song by Teenage Fanclub. It’s their song. Yet when Buddy’s wife, Beth (Elizabeth Reaser), drumming for the all-mom band “Nipple Confusion” at the bar, Champion O’Malley’s (“Where everyone’s a winner”), launches into the band’s opening song, it’s, yep, the same song. One senses that this is now a song Buddy shares with Beth—as he shares a life with Beth. Mavis senses this, too, and for a second she pulls away in anger and disappointment. For a second, there’s clarity. Then she looks over at Matt. He’s eyeing her sympathetically, feeling sorry for her, which, to Mavis, is the exact opposite of the way the world is. She feels sorry for them, not the other way around. So she narrows her eyes and leaps back in. She leans close to Buddy, and shouts, happily, over the music, “I think this song was playing the first time I went down on you!”

She’s delusional about her career, too. A few years earlier, she was written up in the Mercury paper: a “local girl makes good” kind of thing. But in an exchange with a clerk at a local bookstore, it comes to light that: 1) she doesn’t get true author credit on her books; the Waverly Place series creator, “Jane Mac Murray” (the F.W. Dixon of Y.A.), does; and 2) the series isn’t popular anymore. What her publisher wants from her is the last book in the series so he can end it. After which Mavis will have ... what exactly? Not much. She’ll have spent a dozen years writing someone else’s books.

Most importantly, she’s delusional about the way people view her—particularly the people of Mercury. She assumes envy: for her looks, for her career, for the fact that she got out of Mercury in the first place. This envy sustains her. But after Buddy rejects her advances at the baby-naming ceremony (“You’re better than this,” he says with finality), she has a climactic scene with Beth and guests out on the front lawn, in which she spews a rambling, drunken, expletive-laden diatribe against the entire town. Then she beseeches Buddy: “Why did you invite me?” Meaning: Why am I here if you didn’t want to change your life for me? And that’s when her world gets upended. Buddy tells her he didn’t invite her; Beth did. She felt sorry for her. They all do. That look Matt shot her at Champion O’Malley’s? That’s how they all feel. It’s obvious she’s having some kind of mental breakdown. Hey, they just want to help.

Low

There’s been talk of a supporting-actor nomination for Patton Oswalt, but I don’t see it, to be honest. He good, but he doesn’t blow me away the way that Charlize Theron blows me away. The range she displays—from full-on bitchery to abject, near-naked vulnerability—is stunning.

But I do love their scenes together. They have chemistry, and sharp conversation, and both are blunt in a way that the nice folks of Mercury are not. In high school, they had lockers close enough to each other that he remembers the heart-shaped mirror inside hers; but she only remembers him as “the hate-crime guy,” as a victim of a brutal, homophobic jock attack in the woods, which garnered national media attention until it came to light that he wasn’t gay after all. Since it was no longer a “hate crime,” just a horrendous one, it was no longer a story, and the press stopped caring. But Matt carries the reminders. He still walks with crutches. He pisses sideways. He’s a shattered physical reminder—to us—how awful high school was; and he’s a verbal reminder—to Mavis—how awful she was. He mentions the heart-shaped mirror inside her locker. “I think you looked at that mirror more often than you looked at me,” he says.

After the front-lawn debacle, Mavis flees to Matt’s house, which he shares with his sister, Sandra (Collette Wolfe); and as she stands there, vulnerable, askew, fruity beverage spilled over the front of her frilly white dress, he tries to break down her quixotic quest. Why Buddy? he asks. He’s a good man, she responds; he’s kind. “Aren’t other men kind?” he asks. She restarts: “He knew me when I was at my best,” she says, meaning high school. “You weren’t at your best then,” he says. “Not then.”

It’s a great scene. Mavis idealizes her high school years but Matt implies she’s better now, and I tend to agree. Throughout the movie, there’s little that is sympathetic or representative about her—she’s an awful person on an awful mission: a “psycho prom-queen bitch,” in the words of one of Beth’s friends—but there is something representative about her situation. Life didn’t pan out for her. That’s most of us. She lives alone. She’s lonely. Like many. Like Matt. You could say the very thing she’s holding onto—the image of her perfect, high-school prom-queen self—is the very thing she needs to let go if she’s going to have any chance at happiness. And she does. She finally breaks down, and falls into Matt’s arms and into his bed. The whole thing is clumsy and human and thus has a kind of beauty; and when she wakes up the next morning, with Matt’s arm flopped across her waist, echoing the one-night stand Mavis had at the beginning of the movie, we wonder, “What now?”

In Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem,” the chorus goes:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There’s a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

So we’re wondering. Has Mavis forgotten her perfect offering? Has the light gotten in?

Achin’ to Be

Upstairs in the kitchen, she runs into Sandra, gets a cup of coffee, and breaks down further. She’s an open wound now. The walls that protected her are finally gone.

Would “Young Adult” have been as good a movie if it had continued in this direction? I doubt it. The way it ends feels exactly right to me. It feels like a continuation of an earlier, key scene when Mavis, at her parents’ house, wonders why her mother still hangs the wedding photo of Mavis and her ex-husband. Mavis has excised that failed marriage from her life and her mind. It’s part of her non-perfection. But her mother, Hedda (Jill Eikenberry), has her own illusions to maintain—Mavis’ room looks exactly like Mavis left it two decades ago—and, as they sit at the breakfast table, Hedda makes excuses. There’s a pause. Then Mavis offers a non sequitur.

“I think I might be an alcoholic,” she says.

Wow, I thought. But the confession goes nowhere. Her parents deflect it away. Maybe it’s too much reality for them. Maybe they’re unaware of who their daughter really is. Maybe it’s a “not nice” conversation to have at the breakfast table, and this is a nice town, after all, where everyone’s a winner, and so the moment passes—a moment that could’ve been the first step on Mavis’ road to recovery.

Something similar happens at the Freehauf breakfast table. Mavis is breaking down and opening up. She says she doesn’t feel fulfilled. She hates her life. “I need to change, Sandra,” she says. Then Sandra responds:

“No, you don’t,” Sandra says.

Sandra, it turns out, is a Mavis wannabe. She’s the less pretty girl who wants to be the very pretty girl, or at least hang with her, which is what she’s finally doing. Mavis Gary is in her kitchen! She wants to get out of Mercury, too, the way that Mavis did. She still believes in the Springsteenian myth of the town full of losers. “Everyone here is fat and dumb,” Sandra says. “They don’t care what happens to them because it doesn’t matter what happens to them,” she says. “Fuck Mercury,” she says.

Mavis’ reaction? A kind of whoosh. A long exhale. “Thank you,” she says. “Whoa.” Her worldview, upended the day before, is back in place. She doesn’t need to change. It’s the town that’s screwed up. The ironic kicker is that when Sandra asks to come with her to Minneapolis, a trip she hasn’t had the courage to make on her own, Mavis, restored to herself by Sandra, and feeding off of envy again, is sweetly condescending. “You’re good here, Sandra,” she says.

I.e., with the losers in this town. Where everyone’s a winner.

Free to Be, You and Me

Throughout the movie, in fast food joints and park benches, Mavis has been writing her final “Waverly Place” novel, about Kendall and her high school battles, which mirror Mavis and her current battles. One wonders how the novel might’ve ended if Sandra hadn’t opened her mouth. Instead, the Buddy figure in the story winds up dead, “lost at sea,” we’re told, while Kendall, glorious Kendall, graduates high school and leaves town knowing her best days are ahead of her. She leaves town thinking what Mavis probably thought 20 years ago when she left Mercury: “Life: here I come.”

That’s the last line. In the movie theater, I couldn’t stop smiling.

Most of us go to the movies for wish fulfillment. We want to maintain our illusions—that good conquers evil and love conquers all—but by having Sandra bolster Mavis’ illusions, screenwriter Diablo Cody and director Jason Reitman, the team who gave us “Juno,” refuse to bolster ours. We want to believe in self-help notions of progress and betterment, and dramatic notions of resurrection after a fall, and “Young Adult” doesn’t play this game. Mavis’ delusions, close to being killed, are actually made stronger by the end. And over the closing credits we hear Diana Ross sing the following:

Well, I don’t care if I'm pretty at all

And I don't care if you never get tall

I like what I look like, and you're nice small

We don't have to change at all

It’s from the quintessential album of 1970s-style possibility and betterment, “Free to Be, You and Me.” But what’s the promise of that last line? The one thing that can’t be promised. The song’s implication is that, though we change, we can still hold onto the best, unchanging part of ourselves—the part of me that likes you, and the part of you that likes me. It’s a sweet thought, but it’s also the thought that propels Mavis on her psycho-bitch misadventures. What is Mavis saying to Buddy throughout this film if not what Diana says at the end of the song? “I don't want to change, see, because I still want to be your friend—forever and ever and ever and ever and ever.”

I assume all of this is too cynical for most moviegoers. I assume that’s why the movie hasn’t done better. To me, it felt like a breath of fresh air. To me, after the supercharged lies of most movies, it felt a little like life.

—January 19, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard