Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

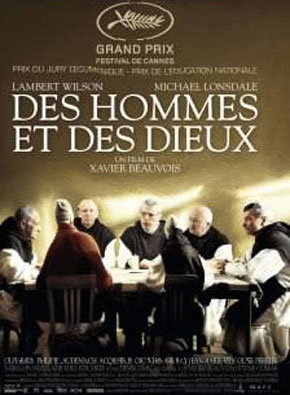

Of Gods and Men (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Of Gods and Men” is a monastic movie. It’s filmed as unaffectedly as the Cistercian monks lived their lives, and gave their lives, in Tibhirine, Algeria, in 1996. It documents their modest activities in a modest manner. We see them carry firewood and clean floors. They pack honey, miel de l’Atlas, and sell it at the local market. They farm, tend to the sick, help procure visas. They study—both St. Augustine and the Koran. They pray and sing hymns and psalms. A true review of the picture would be written equally modestly, using short, plain sentences, but I know myself too well and promise nothing.

Going in, I didn’t realize Xavier Beauvois’ movie was based upon a true story. From a 1996 article in The New York Times:

French and Algerian authorities said today that the bodies of seven French monks killed by the rebel Armed Islamic Group had been found near the monastery south of Algiers where they had been kidnapped two months ago. ...

The murders set off a wave of public outrage in France, and 10,000 people, led by Prime Minister Alain Juppe, marched on Tuesday night to Trocadero Square, where the Declaration on the Rights of Man was signed nearly a half century ago, for a moment of silence.

The Armed Islamic Group ... has been waging an armed struggle with the Algerian Government since 1992 ...

We get that armed struggled by and by. Between visa paperwork and evening prayers, the head of the monastery, Brother Christian (Lambert Wilson), a tall, spectacled man who likes to walk in the woods and feel the bark of trees, meets with local leaders, who complain about a recent murder: how a new breed of religious insurrectionist slit a girl’s throat and threw her off a bus for not wearing a hijab. “For a veil!” one of the leaders says with disgust. “They say they’re religious but they’ve never read the Koran.” Christian listens, worry in his eyes.

Shortly after, cars and vans pull up at a construction site, and the foremen, later identified as Croatians, have their throats slit. The news quickly descends on the monastery, along with people and advice. The monks are told they need military protection but Brother Christian makes a stand. “Je refuse,” he says.

That line sounds great, and even better in French, but this is not a Hollywood movie with its love of absolutes. The monks’ courage is tinged with fear. Their faith is tested by doubt and silence. At a round-table discussion, the first of many, they discuss the problem of both leaving and staying: “We were called here” vs. “I didn’t come here to commit collective suicide.” Things are left undecided, life continues, fear remains.

One evening, as Brother Paul (Jean-Marie Frin) goes to lock the gate, those fears are realized. A group of terrorists, led by Ali Fayattia (Farid Larbi), burst in with machine guns drawn and demand to see “the Pope.” Told they have no Pope, he declares, “The leader! Who’s the leader here?” Christian emerges, nervous and upset. He tells Fayattia no weapons are allowed inside a house of peace. When Fayattia tells him his weapon never leaves his side, Christian nods, says, “We’ll talk outside,” and moves past him. By the gate, Fayattia demands the doctor, Brother Luc (the superb Michael Lonsdale), to care for one of his men, who’s wounded, but knowing Luc’s age and health, this, too, Christian refuses.

Fayattia: Vous n'avez pas le choix. (You don’t have a choice.)

Christian: Si, j'ai le choix. (Yes, I do.)

The movie keeps coming back to not only the desirability of choice (the right to choose) but its undesirability (the weight, the difficulty, of choosing). “J’ai le choix” leads to How do I choose? What do I choose?

Christian, armed only with faith and truth, gives Fayattia a choice: he can bring his man to Brother Luc or he can seek care elsewhere. Then he suggests asking around about the monks and he’ll find they’re modest men of modest means. Finally he quotes from the Koran: “You shall find the closest to you in love and kindness shown to the believers are those who say we are Christians, for among them are priests and monastists, and they are not arrogant.” When Christian finally mentions that that night is Christmas Eve, the birth of the savoir, Fayattia, as stern as ever, actually apologizes.

That’s the scene but I haven’t conveyed its power. The refusal is made from a position of weakness, the apology from a position of strength. All of it solves nothing, least of all the monks’ dilemma.

They are basically caught in a civil war and are metaphorically being shot at from all sides. A government official, urging them to leave, says, “Your courage will be exploited,” and blames the civil war on the vestiges of French colonialism. When Christian tells neighborhood leaders that the monks feel like birds on a branch, wondering whether to take off, the leaders, who want them to stay, disagree with the metaphor and substitute a Christian one. “No, we are the birds. You are the branch.”

The most profound angst is felt by Brother Christophe. Olivier Rabourdin, the actor, has a tough face, but Christophe, the character, has trouble locating his inner toughness. When Christian tells him he needn’t fear for his life because he already gave his life, to Christ, Christophe admits, “I pray ... and I hear nothing.” We see him in the attempt. The others hear him in the attempt: “Help me, help me, don’t abandon me.” Tensions mount. Washing dishes, Luc makes an offhand remark. “Fuck off,” Christophe says, and walks away. I believe it’s the film’s only profanity.

We don’t see enough of Luc, by the way, who has a wise, quiet charm. He’s gentle with patients and impatient with government officials questioning his patients. “I’m not scared of death,” he tells Christian at one point; then adds with a smile, a touch of monastic jocularity perhaps: “I’m a free man.” In an early scene, he sits on a bench in the winter sun talking to a local girl about love. She wonders what it feels like, and we, or the romantics in us, suspect she’s in love. When he gives her a description of love that is both simple and beautiful—“Something inside you comes alive...” he says, “but you’re in turmoil, especially the first time”—she responds, No, she’s never felt that, and certainly not with the boy her parents want her to marry. “Oh, c’est ca,” Luc answers. She asks Luc if he’s ever been in love and he answers, yes, several times. “Then I experienced an even greater love and I answered that call. Sixty years ago.” It’s such a beautiful scene I didn’t want to leave it. It shows us not only how much these Christian monks are part of the life of this Muslim village but why. They don’t proselytize about Jesus’ love; they quietly demonstrate it.

Later we see the same girl farming with Brother Christophe; then we don’t see her so much. One wonders what happens to her, this modern Muslim girl, caught between a corrupt government and reactionary revolutionaries. It can’t have ended well.

It doesn’t for the monks. Christian is asked to identify the body of Ali Fayattia, captured by the military, mutilated by villagers, and his response before the body—sadness and prayer—irks the military official. Suddenly the monks are dealing with raids from the government, and helicopter hoverings from the government, but in the end it’s the Armed Islamic Group, A.I.G. (those initials are never good) who kidnap them. Earlier, when contemplating what to do when the terrorists came, Luc jokingly suggests hide-and-seek. “On peut jouer à cache-cache?” He also declares the elfin Brother Amedee (Jacques Herlin) fit after a medical exam with the words, “You’ll outlive us all.” Both jokes are prophetic. Brother Amedee hides from the terrorists beneath his bed, and when seven of the nine are taken, he outlives them all save for Brother Jean-Pierre (Loïc Pichon).

Is the Tchaikovsky too much? In the scene before the kidnapping, Luc nonchalantly plops two bottles of red wine on the kitchen counter, and plays, from a beat-up tape recorder, Tchaikovsky’s Grand Theme from “Swan Lake.” The monks drink, slowly, and slowly enjoy each other’s company, and come to tears. Some think the scene too much, in its echoes of the Last Supper, in its apparent foreknowledge of death, but I found it beautiful: not only for itself, but for how it highlights, retroactively, just how modestly these monks lived their lives. For them, a glass of wine, and tape-recorded Tchaikovsky, is an event.

A translation question: How did “Des hommes et des dieux” in French become “Of Gods and Men” in English? Why not “Of Men and Gods”? My friend Jake raises a more telling point: Is the plural of God, or dieu, necessary in either title? The film suggests, at various points, one God for us all, all religions, particularly at the end. As the camera focuses on familiar monastery rooms, now empty of life, we hear the letter Brother Christian wrote in event of his violent death. That letter, translated into myriad languages, is akin to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”: a strong Christian stance to violence and immorality.

He begins:

Should it ever befall me, and it could happen today, to be a victim of the terrorism swallowing up all foreigners here, I would like my community, my church, my family, to remember that my life was given to God and to this country; that the Unique Master of all life was no stranger to this brutal departure; and that my death is the same as so many other violent ones, consigned to the apathy of oblivion ...

He ends with words so beautiful I have nothing to add:

My death, of course, will quickly vindicate those who call me naïve or idealistic, but I will be freed of a burning curiosity and, God willing, will immerse my gaze in the Father's and contemplate with him his children of Islam as he sees them. This thank you which encompasses my entire life includes you, of course, friends of yesterday and today, and you, too, friend of the last minute, who knew not what you were doing.

Yes, to you as well I address this thank you and this farewell, which you envisaged. May we meet again, happy thieves in Paradise, if it pleases God, the Father of us both.

Amen. Insha'Allah.

—April 25, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard