Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

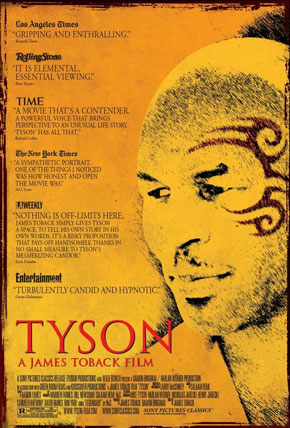

Tyson (2009)

WARNING: HEAVYWEIGHT SPOILERS

The most surprising admission in “Tyson,” James Toback’s documentary about former heavyweight champion Mike Tyson, isn’t that Tyson was scared heading into the ring, nor that he wanted women to protect him—him, the baddest man on the planet. It’s this: When he was young, Mike Tyson was Woody Allen.

The revelation comes early in the doc, which consists almost exclusively of old fight footage and present-day Tyson interviews. Tyson, bald now, Maori warrior tattoo sweeping one side of his face, and dressed in a pressed, button-down shirt and slacks in a Hollywood mansion, tries to explain who he is by explaning where he came from: the Brownesville section of Brooklyn, where, he says, it was “kill or be killed.” He talks about getting picked on. He talks about getting money stolen from him—quarters and change—by neighborhood gangs. Then he talks about how someone once took his glasses and broke them. The image that comes to mind is Virgil Starkwell forever having his glasses stomped on by bullies in “Take the Money and Run.” Mike Tyson was Woody Allen? Who knew?

A second later you narrow your eyes. Wait a minute. Glasses? Did Tyson need them as a kid? Did he stop needing them as an adult? You believe Tyson when he says, of the man who lived with his mother: “He might have been my father... I believe he was my father... I was told he was my father”— a sequence that Toback splices together to great echoing effect. But the glasses thing?

Or was he talking about sunglasses?

That’s part of the challenge of “Tyson.” How much do you buy into what he’s saying? When is he bullshitting us? When is he bullshitting himself? And when is James Toback putting too personal a stamp on Tyson’s story? Half the film is rise and half is sad fall, and Toback ends the first part with Tyson saying, “Once I’m in the ring, I’m a god. No one can beat me.” Then we get a slow fade and a slow open on Robin Givens. The implication is that everything began to go wrong with her, but, truly everything began to go wrong with the “god” comment and the hubris it represents. Pride, as always, goeth.

Tyson was trained by Cus D’Amato—who deserves his own doc, and who died in November 1985, a year before Tyson knocked out Trevor Berbick in the second round to become heavyweight champion of the world. Then he was trained by Kevin Rooney, but Tyson fired him in late 1988. He was managed by Jim Jacobs and Bill Cayton. But Jacobs died in March 1988 and Don King suddenly insinuated himself into the picture, fighting and apparently beating Cayton over Tyson’s contract. Why did Tyson go along with this? What part did racial politics play? And why doesn’t the doc focus on it more? Toback blames the lack of training, the partying, the women, but all of this is related to a larger issue: Tyson stopped dancing with those who brung him.

Tyson is surprisingly kind to Givens. He calls her “this young lady.” He says “everyone was in our business.” He says “We were just kids, just kids, just kids.” He doesn’t know why she lied to Barbara Walters on national television—Givens, with Tyson hanging over her shoulder, tells Barbara, and the country, that Mike, the heavyweight champion of the world, is a manic depressive, that their marriage has been pure hell, that “it’s been worse than anyone could imagine”—but in this doc he more or less gives her a bye.

Not so with others. “When I was falsely accused of raping that wretched swine of a woman, Desiree Washington, it was the most horrible moment in my life,” he says. He calls Don King “just a slimy, reptilian motherfucker” who would “kills his own mother for a dollar.”

He’s also hard on himself. He owns up to a lot. That he likes strong women whom he can sexually dominate. That when Cus D’Amato first takes him to his mansion, he’s thinking of robbing him: “I could rob this white guy,” he thinks.

He breaks down on camera talking about Cus. It seems the most important relationship in his life. At the same time he says, “I was like his dog. He broke me down. He broke me down and rebuilt me.” Cus also gave him speed, power, confidence. The doc is separated between those who built up Tyson’s confidence (D’Amato, mostly) and those who tore it down (Givens, Washington, King).

Remember how fierce he was? He had 15 fights in 1985 and won all of them by KO or TKO, 11 of them in the first round. He was built like a bullet and seemed just as unstoppable. He was so tough he inspired the toady in other men. Hell, I even felt it from afar, joking about his prowess in the ring, luxuriating in his power as if it were in any way related to my own (lack thereof). Or maybe I simply liked how much of a unifying concept he was in an increasingly fragmented world. He unified all the heavyweight belts that had been scattered to the four winds. For years no one argued over who the best boxer was. The only question was the question the announcer asked after Tyson destroyed Michael Spinks at 1:31 in the first round in a heavyweight bout in 1988: “Who in this world has any chance against this man?”

Himself. He was not a god. Gods don’t have to train, but he did, and he lost to Buster Douglas in 1990 in one of the greatest upsets in boxing history. We kept waiting for him to unify things again but he kept stumbling. First the rape charge, then the conviction. He lost three years. When he came out of prison, he was a Muslim. This too seems sad, like it was part of someone else’s story, as it was. It was Malcolm’s and Muhammed Ali’s. Tyson was clinging to cliches.

I’d forgotten that he won the heavyweight championship again in the mid-1990s. And I didn’t know, in the infamous ear-biting match with Evander Holyfied, that Tyson claimed Holyfield headbutted him first. I’m not a boxing fan so I didn’t know. But I knew so much else because Tyson seeped through to the general culture in a way no boxer has since. Who’s even the heavyweight champ now? I had to look it up. A Russian and two Ukranian brothers. Three Great White Hopes. We’re fragmented. We’re scattered to the four winds.

“Tyson” is an untraditional doc in that there are no other talking heads. Would it have been better with other voices? Maybe. Would it have been better without Tyson walking along a Malibu beach? Yes. That Hollywood home, it turns out, was rented by Toback. So where does Tyson live? Why didn’t they film there? Why this fake Hollywood backdrop?

It’s still effective. The former champ seems lost in the way of former champs. “Old too soon, smart too late,” he says. “”What I’ve done in the past is a history, what I’ll do in the future is a mystery,” he says. The final shot is a freezeframe on his battered, confused face. He once thought himself a god. Now he’s just another man who can’t make sense of his life.

—August 30, 2009

© 2009 Erik Lundegaard