Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

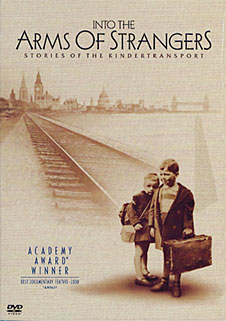

Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport (2000)

Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport is a quiet, heartbreaking documentary that details a little-known aspect of the Holocaust. From December 1938 to September 1939, Jewish children from Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland were allowed to emigrate to England provided they had host families and a £50 guarantee against re-immigration. The stories told here, by more than a dozen survivors, are filled with great horrors and small hopes and, as one surviving parent describes it, a hurt that "cannot be described."

Written by:

Mark Jonathan Harris

Directed by:

Mark Jonathan Harris

Narrator:

Judi Dench

Featuring:

Lorraine Allard

Lory Cahn

Kurt Fuchels

Alexander Gordon

Franzi Groszmann

Eva Hayman

Jack Hellman

Bertha Leverton

Ursa Rosenfeld

Lore Segal

Robert Sugar

Norbert Wollheim

Academy Awards:

Best Documentary

Quote:

"But the hurt is unbelievable. That cannot be described."

Further reading:

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum site

If you were a Jewish family in 1930s Germany, the world closed in gradually. Ursa Rosenfeld first sensed what was happening when no one showed for her birthday party. But in Austria and the Sudetenland, which were both annexed in 1938, the anti-Jewish laws were put in place swiftly. Almost overnight, Jewish children were banned from schools, parks, theaters and swimming pools, and on November 9, 1938, Kristalnacht, the Night of Broken Glass, erupted. Jewish businesses were destroyed, Jews were rounded up, rabbis beaten, torahs trampled. The next morning as Ursa watched a synagogue burn, she heard someone say, "There's a Jew! Let's throw her on the fire as well!" The same day her father was arrested. Eventually he was sent to Buchenwald where, when he objected to the treatment of older men, he was beaten to death. Ursa remembers, matter-of-factly, "They offered us my father's ashes in return for money, and eventually the urn came. And we buried it in the Jewish cemetery. Of course, whether it was his ashes, we'll never know."

Although the world condemned the Nazis for Kristalnacht, only Great Britain was willing to relax its immigration policies, and only then for children, since it was felt adults would place too great a strain on the job market. (In the U.S., a bill which would have admitted 20,000 child refugees died in committee, in part because "accepting children without their parents was contrary to the laws of God.")

As a result, Jewish parents in greater Germany worked feverishly to get their children to England — to ensure their safety by sending them away. Each survivor remembers the anguish of the train station goodbye, the terror caused by the Nazi border guards and the relief in Holland as Dutch ladies brought them cocoa and zwieback.

Stories in England vary greatly. One older girl was made a servant in her foster home. A boy who had been beaten and tossed through a window in Tann, Germany, was sent to a luxurious manor in Buckinghamshire. Many of the refugees were forced to stay in temporary camps in Dovercourt, where they were fed such odd fare as "kippers," and where possible host parents looked them over in a cattle market atmosphere.

The power of Into the Arms of Strangers lies in how quietly it tells us about the unspeakable — in how matter-of-factly everyone describes moments of emotional upheaval. Eva Hayman, of the Sudetenland, remembers the night before she and her sister were sent away: "Both mother and father," she says, "were trying to give their instructions and guidance that they hoped to have their whole lives to give." One father couldn't bear the separation and literally pulled his daughter from the train as it began to leave the station. The girl wound up at Auschwitz.

Of course most of these children never saw their parents again, and even those that did were forever scarred. "My parents let go of a seven year-old," Kurt Fuchels remembers, "and got back a sixteen year-old."

Yet each survivor knows how lucky they were. Ostracized, yes, uprooted, torn from family and home, forced to grow up with people who didn't love them. Still, they survived. Unlike 1.5 million Jewish children who didn't.

—November 27, 2001

© 2001 Erik Lundegaard