Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

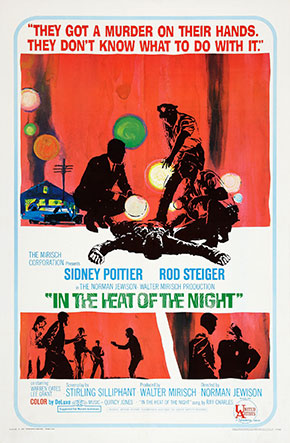

In the Heat of the Night (1967)

Some Best Picture winners age well and some don't, and unfortunately In the Heat of the Night belongs in the latter category. One reason: race. Heat was made at a time when the Civil Rights Movement was dying and the Black Power Movement was beginning, and the filmmakers didn't quite know what to do with their leading man, Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier). Obviously he couldn't be Stokely Carmichael — white people wouldn't see that film — but he couldn't exactly be Dr. King either. And if he's not Dr. King, how do you get him to stick around Sparta, Mississippi to help dim, racist Police Chief Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger)? The filmmakers' answer ultimately weakens the picture.

Written by:

Stirling Silliphant

(from the novel by John Ball)

Directed by:

Norman Jewison

Starring:

Sidney Poitier

Rod Steiger

Lee Grant

Warren Oates

Larry Gates

James Patterson

Academy Award Nominations:

Best Director

Best Sound Effects

Academy Awards:

Best Picture

Best Actor (Steiger)

Best Screenplay

Best Editing (Hal Ashby)

Best Sound

Quote:

"They call me Mister Tibbs!"

The movie opens with Deputy Sam Wood (Warren Oates), making his midnight rounds, and stumbling upon the murdered body of northern industrialist Philip Colbert (Jack Teter) in an alleyway. Right away we sense Police Chief Gillespie is out of his element. As he looks down upon the body and works furiously on a piece of gum, he suggests, "Could've been a hitchhiker." Weak guesses are all he's got. At the train station, Wood finds and arrests Virgil Tibbs, a well-dressed black man with money in his wallet. Tibbs is no patsy, though; he's a Philadelphia homicide detective who's smarter than the Sparta police. He knows it and they know it. Steiger, in fact, does a great job of demonstrating Gillespie's divided soul. Once he finds out who Tibbs is, he wants his help; at the same time he can't stand asking.

But Mrs. Colbert (Lee Grant) has little faith in the competence of the local police, and she wants Tibbs on the case. Plus Tibbs' superiors in Philadelphia have agreed to loan him to Sparta (does this happen often?), so Tibbs is stuck. Except the next morning Gillespie chases down and arrests another drifter, and thinking he no longer needs Tibbs, dismisses him, calling him a nigger. Alas, he has the wrong man (again) and has to travel to the train station to win Virgil back.

Much of the interaction between Gillespie and Tibbs is great. During the autopsy, Tibbs baits Gillespie's lack of intelligence ("As you know, loss of heat from the brain is the most accurate way of detecting time of death. Right, Chief?"), while Gillespie mocks Tibbs' effeminate first name and hifalutin ways. But the train station scene doesn't work at all. At this point in the film, Tibbs has no good reason to stick around. He's been called nigger and boy by the police; he's been falsely arrested, and his detective work has largely been ignored. He's not close to solving the case, and his later rationale for sticking around — to stick it to Endicott, the modern plantation owner — hasn't been introduced, because he hasn't been introduced to Endicott. So why stay? In fact, Gillespie gives him every reason not to stay by angrily saying he'd like to horsewhip him for his stubbornness. Given the history of whipping in the American south, one expects an explosion from Tibbs. Instead he looks amused, rubs the top of his head in thought, and says, "My father used to say that to me..."

The picture lost me right there.

Because Tibbs might have thought his line, but there's no way he'd ever say it out loud — particularly to a racist southern sheriff he hardly knows. Much of the movie is like this: the more authentic Gillespie seems, the less so for Tibbs. Probably why Steiger won the Academy Award for Best Actor, while Poitier wasn't even nominated.

In the Heat of the Night is still a good movie, with excellent cinematography from Haskell Wexler. But in racial matters, it rings false 30 years later.

—April 29, 2001

© 2001 Erik Lundegaard