Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

Le Amiche (1955)

WARNING: CAT’S-EYE SPOILERS

After Patricia and I watched Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Le Amiche” (1955) on DVD last week, which my friend Vinny and I had seen last August at the Northwest Film Forum, she looked at me, shook her head, and, referring to the mostly female cast and their mostly female concerns, said, “I can’t imagine you and Vinny seeing this together. What did you talk about afterwards?”

“What guys always talk about,” I said, shrugging. “Which woman we’d like to bang.”*

(*For the record, I chose Momina, Yvonne Furneaux, who made 41 movies overall, including “La Dolce Vita” and “Repulsion,” while Vinny went for Mariella, Anna Maria Pancani, who, for some reason, made just four movies, three in 1955. Both actresses are apparently still alive.)

The movie begins as a kind of mystery. Clelia (Eleonora Rossi Drago), recently arrived in Turin, Italy, where she is to set up a branch of the Ferreri fashion salon, prepares a bath in her hotel room when she encounters a would-be suicide, Rosetta (Madeleine Fischer), in the next room. The maid screams, declares the woman dead, but Clelia, cooler-headed, takes a pulse and calls for an ambulance.

Cops come, followed by Momina de Stefani (Yvonne Furneaux), Rosetta’s well-heeled, opinionated friend, who enlists Clelia to help uncover the mystery. Why did Rosetta do it? Momina, seeming to enjoy this amateur sleuthing more than the circumstances should allow, quickly discovers that Rosetta repeatedly tried the same phone number before taking her sleeping pills. Then she quickly discovers that that someone is Lorenzo (Gabriele Ferzetti), a married artist, who recently painted a portrait of Rosetta. But surely that’s not the end of the mystery. Yes, it’s the end of the mystery. Rosetta loves Lorenzo, Lorenzo didn’t know it, but he takes advantage of it once he does. Antonioni isn’t interested in Rosetta’s mystery the way Hitchcock would be. He merely uses it to introduce us, and Clelia, into this circle of friends, and the deeper, more existential mysteries of friendship, love, work, and being.

The world of le amiche, where the blinds are never closed.

A lot of flitting and flirting goes on. As viewers we wonder: Who is whom? And who is with whom? Clelia arrives at the salon to find everything horribly behind schedule, and lays into both the architect, Cesare (Franco Fabrizi) and his assistant, Carlo (Ettore Manni), and winds up in a relationship with the latter, while the former flirts, and makes out with, Mariella (Anna Maria Pancani), a yummy, carefree thing, but becomes the lover of Momina, who is married to but separated from a husband who, Green Acres-style, apparently prefers the countryside.

Momina, my choice

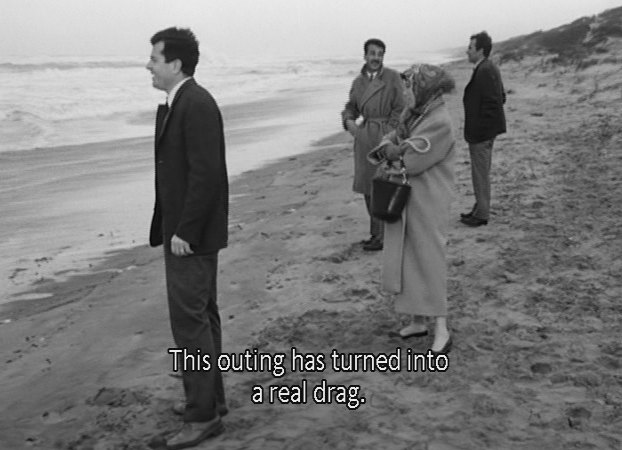

There’s a great set-piece, a Sunday trip to the beach in winter, where everything goes wrong. The ocean looks dirty, there aren’t enough men, the women can’t hide their true natures. The trip is ostensibly to draw out Rosetta but instead Rosetta is insulted by both Mariella (openly) and Momina (surreptitiously), and these two fight over Cesare, who, despite a large nature, doesn’t seem worth fighting over. Nene (Valentina Cortese), Lorenzo’s wife, clings to him, sensing his distance, and, as the afternoon wears on, one of the background men, watching the waves, simply declares, “This outing has turned into a real drag.”

A winter day at the beach: The ocean looks dirty, there aren’t enough men, the women

can’t hide their true natures.

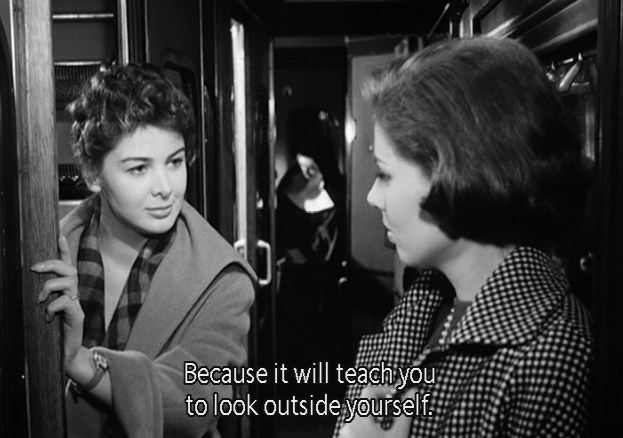

It’s up to Clelia to salvage things by essentially holding Rosetta’s hand during the trainride back to Turin. Broken heart? She counsels work. It’s what’s saved her. “Very few people can be self-sufficient,” she says. “We can’t do without other people. It’s no use thinking you can.” Between them, in the background, we see a nun, representing another way out, another form of self-sufficiency. Is it the nightmare of all women or the salvation? Either way, it’s there, hanging in the words between them.

Clelia and Rosetta talk life choices, with a nun between them.

The mystery of Rosetta turns out to be not very interesting because Rosetta turns out to be not very interesting. She wants Lorenzo. When she gets him, despite the betrayal to Nene, she’s happy. When she loses him again, she finally kills herself, despite the fact that Lorenzo is definitely not worth killing yourself over. He’s a weak man, who romances a would-be suicide because he can, and who can’t abide his wife’s greater artistic success. Momina nails him immediately. After Lorenzo leaves his gallery huffily when a customer professes interest in Nene’s ceramics rather than his paintings, Momina tells Nene, coolly, “He’s just jealous of your success.” He stays that way. Nene is offered an opportunity with a big gallery in New York, but he stunts her, and Nene allows herself to be stunted out of love for this man.

Nene and Clelia, so similar in temperament, turn out to be opposites in life choices. Nene is the compassionate insider who chooses a man over work, while Clelia is the compassionate outsider who chooses work over a man, Carlo, whom, at the end, she leaves behind at the train station. The movie bookends itself well. It begins with a suicide (attempted) and ends with a suicide (real). It begins with a woman arriving in Turin and ends with her leaving it. And in the middle? Much ado about nothing. Everyone clings to something to give life meaning—work, a man, many men. Girlfriends, le amiche, are someone to pal around with during that search; during the mystery that isn’t much of a mystery. Everyone strains so the outing doesn’t turn into a real drag.

Carlo doesn't know it, but Clelia is already out of the picture.

—March 10, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard