Wednesday December 17, 2014

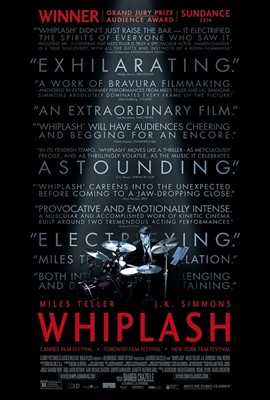

Movie Review: Whiplash (2014)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I thought “Whiplash” was about a sadistic teacher who makes life hell for an innocent kid who just wants to be a jazz drummer.

Instead, “Whiplash” is about a sadistic teacher who makes life hell for an arrogant bastard ... who just wants to be a jazz drummer.

So it’s much better than I thought.

At first, Andrew (Miles Teller) seems another fish-out-of-water kid. He’s at a prestigious school, Shaffer Conservatory of Music, seemingly without friends, and goes to the movies (“Rififi”), with his father, Jim (Paul Reiser), a put-upon teacher whose wife left soon after Andrew was born. At the theater, an unseen man bumps Jim’s head with a bucket of popcorn and it’s Jim who apologizes. He’s that kind of guy.  The kind of guy, it turns out, that Andrew doesn’t want to be.

The kind of guy, it turns out, that Andrew doesn’t want to be.

The movie opens with Andrew on the drum kit, playing away, when the school’s best teacher, Terrence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons), arrives and listens. Andrew stops when he sees Fletcher. “Why did you stop playing?” Fletcher asks. So Andrew starts again. “Did I ask you to start playing again?” Fletcher says. “Show me your rudiments.” The kid is desperate for attention and Fletcher enjoys not giving it. He leaves without a word (to Andrew’s disappointment), then returns (to Andrew’s relief). But instead of encouragement, he says, “Oopsie-daisy, forgot my jacket.” Then gone again.

The “oopsie-daisy” is like a little knife in the side. The knives will get bigger.

Third division

Initially we think Andrew is like us—just more talented. But he’s not like us. And he doesn’t want to be.

This becomes painfully clear at an extended family dinner. His accomplishment—making Fletcher’s class—is run over by family talk, and when he returns to it no one seems to get it. They shouldn’t, really. Fletcher? Who’s Fletcher? Plus it’s jazz, not football. Now Uncle Frank’s boys, they’re on the football team. “Yeah,” Andrew says dismissively, “third division.” In the next minute, we get Andrew’s philosophy. It’s all about the work, the music. Friends? Family? They just get in the way. Charlie Parker is held up as the exemplar, to which Jim mentions his drug-addled death. Andrew’s response? “I’d rather die drunk, broke at 34, and have people at a dinner table talk about me, than live to be rich and sober at 90 and nobody remembered who I was.”

In this sense he’s the perfect student for Fletcher.

Is that why Fletcher focuses on him so much? Because he senses this drive in him? The anecdote that’s constantly brought up is that moment in 1937 when drummer Joe Jones threw a cymbal at a teenage Charlie Parker. Parker was humiliated, but practiced for a year until he was, well, Bird. Then he blew everyone away. That’s what Fletcher says he hopes to do: be the Joe Jones who brings out the Bird in a new Charlie Parker.

Does he see that in Andrew? Or is it simply the sadist feeling out the masochist? Because—beyond an introductory lesson in humiliation in which Fletcher calls out a student for being out of tune (even though he wasn’t)—Fletcher focuses completely on the drum kit.

Andrew starts out as alternate, replaces 1st drummer Carl (Nate Lang) when he misplaces Carl’s sheet music, then competes with both Carl and Ryan (Austin Stowell) for 1st chair, and Fletcher’s attention. Fletcher keeps them all off balance and yearning. With Andrew, he tells him he’s rushing or dragging. “Not my tempo,” he says over and over.

That’s among the nicer things he says. His talent for invective would give R. Lee Ermey a run for his money:

- Parker, that is not your boyfriend’s dick: do not come early.

- If you deliberately sabotage my band, I will fuck you like a pig.

- Oh dear God, are you one of those single-tear people? You are a worthless pansy ass who is now weeping and slobbering all over my drumset like a 9-year-old girl!

Also this: “There are no two words in the English language more harmful than good job.”

Does the movie agree with this assessment? Is this a wake-up call for the audience, sitting in the dark, listless, munching on popcorn and wish fulfillment, about what it really takes to get ahead? The rest of us are the family at the dinner table, or Jim apologizing because someone else was rude, or Nicole (Melissa Benoit), whom Andrew dumps two scenes into their relationship because she’ll just get in the way. Andrew, willing to get blood, sweat and tears on the kit, is ruthless in his determination. That’s why he gets where he does.

I buy that argument to some extent. In my own life, I’ve made choices, and they’ve invariably been “Minnesota Nice” choices. What ruthlessness I’ve displayed is usually followed by pangs of guilt and self-abnegation. I think most of us feel trapped between these two unpalatable options: getting run over by life, like Jim, or being a massive asshole like Fletcher.

But there are other options.

Twenty-game winner

The counterbeat to all of this played in my head even as the story played out onscreen. It’s the story of Ferguson Jenkins. I don’t remember where I read it—I can’t find it online—but he was a pretty good player, a Major Leaguer, certainly, but he wasn’t great yet. Then a coach instilled confidence in him. The coach made him believe he could be what he became: one of the great pitchers of his era, a 20-game winner for six years in a row, and an eventual Hall-of-Famer. That coach built up; this one tears down.

“Whiplash” is written (sharply) and directed (beautifully) by first-timer/squeaker Damien Chazelle, and it progresses smartly. Andrew’s bus breaks down on the way to a concert, he has to rent a car to get to the hall—but he leaves his drumsticks behind. When he goes to retrieve them, there’s a car accident, a truck upending his rental (beautifully filmed), and Andrew crawls from the wreckage and runs to the show, where, despite being in shock, despite being bloodied unable to hold his sticks, he sits in. Does Fletcher appreciate this? Show concern? No. After Andrew flubs it, Fletcher dismisses him. Then Andrew attacks him and is expelled; then he becomes an unnamed part of a lawsuit against Fletcher for abuse. An earlier student, whom Fletcher had held up as an exemplar (and who died, he said, in a car accident), had actually hung himself—in part, the lawyers say, because of the years of psychological abuse Fletcher had inflicted on him.

When Andrew sees Fletcher again, he’s playing piano in a jazz club, and he asks Andrew to play drums with his band at the JVC Jazz Festival at Carnegie Hall. Andrew hasn’t been practicing much since his expulsion, and he’s slightly worried as he sits at the kit. Someone doesn’t play well at JVC, they’ll probably never get another gig. That’s the idea. And that’s Fletcher’s idea. Because he knows it was Andrew who ratted, and he begins with a song that Andrew has never practiced, and for which he has no sheet music. He’s humiliated, leaves the stage and collapses into the arms of his father, who consoles him.

The end? No. He doesn’t join the Jims of the world. He goes back and fights the Fletchers.

Andrew returns to the kit, and without instruction begins playing; then he tells the band when to join in, and they do. (Why do they listen to him exactly? What’s the protocol on this?) It’s like he’s taking away Fletcher’s band from him. He’s the leader now. But that’s not it either, exactly. There’s no comeuppance for Fletcher. By the end, Fletcher and Andrew are working together. You can see Fletcher’s eyes light up in a way they haven’t yet. He’s wondering if this is the moment. He’s wondering if he’s finally getting his Charlie Parker.

It’s a triumphant ending. Two jerks create something beautiful. That's kind of ... beautiful.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)