Wednesday December 03, 2014

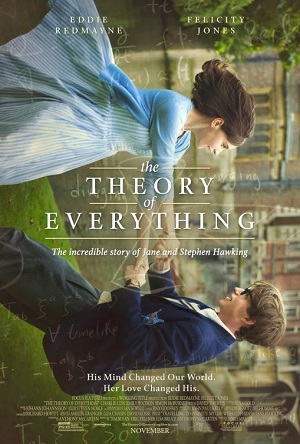

Movie Review: The Theory of Everything (2014)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Ohhh. Based on the book by Jane Hawking.

I assumed “The Theory of Everything” was mostly about Dr. Stephen Hawking, his cosmic theories, and his battle with ALS—with a bit of romance and relationship tossed in. And that’s how it goes for, say, the first third of the movie, which is the most interesting part.

After that, it’s mostly about the relationship. Specifically, it’s about the deterioration of the relationship: how Jane (Felicity Jones) gets fed up with caring for the kids and Stephen; how she doesn’t have time for her own work—something to do with medieval Spanish poetry—and how he doesn’t even believe in God, even though she does, and so she returns to the church choir, where, look! My, what a handsome man! Hey, isn’t that the same dude who romanced Margaret away from Nucky in “Boardwalk Empire”? Is actor Charlie Cox doomed to play The Other Man? The one who lures women into affairs with a simple smile? (Yes.)

As for the point of Hawking? Our place in the cosmos? The meaning of time and space? Whatever, Brainiac. Read a book already.

In this way “The Theory of Everything” is the Carrie Bradshaw of movie biopics. They make it all about her.

Two years to live

At Cambridge in 1963, Hawking (Eddie Redmayne), sporting a Beatles haircut a year early, meets and romances Jane, stumbles and knocks things over, and is a genius.  This last is dramatized with the usual cinematic shorthand. His professor, Dennis Sciama (David Thewlis), gives his Ph.D. students 10 increasingly difficult questions to answer, and Stephen, mooning over Jane, doesn’t get to them until the morning they’re due. Then he arrives late to class, where the professor is berating the students for their inability to make any headway. Stephen, apologizing, hands over his answers on the back of a train timetable. “I could only do nine,” he says. Everyone looks at him in astonishment.

This last is dramatized with the usual cinematic shorthand. His professor, Dennis Sciama (David Thewlis), gives his Ph.D. students 10 increasingly difficult questions to answer, and Stephen, mooning over Jane, doesn’t get to them until the morning they’re due. Then he arrives late to class, where the professor is berating the students for their inability to make any headway. Stephen, apologizing, hands over his answers on the back of a train timetable. “I could only do nine,” he says. Everyone looks at him in astonishment.

See? Genius.

It’s kind of fun, actually. It’s like the revelation of a super power, but for awards season. Spring and summer are all about the superstrong and superfast, but in the fall we get the supersmart. As well as the achingly British.

From there, Prof. Sciama takes him to see an even more brilliant scientist, Roger Penrose (Christian McKay from “Me and Orson Welles”), who explains to everyone—mostly us—what black holes are. And from this discussion, Stephen extrapolates back to the origins of the universe and the big bang theory.

I like this part. I like the beginning of the romance, too. Their first discussion at a Cambridge mixer makes Hemingway seem verbose:

He: Sciences?

She: Arts.

He: English?

She: French and Spanish

He tries to explain to her—and us—what he does. He’s searching for a “single unified equation that explains everything in the universe.” (Obvious unasked follow-up: Why do you think it exists?)

Then the big fall on campus that leads to the discovery that he has a motor-neuron disease. Signals from his brain are no longer getting to his muscles; it’s as if the two stop talking. (A good metaphor that the film could use later but doesn’t.) We get another good scene with his lifelong friend, Brian (Harry Lloyd), who simply thinks Stephen’s had a bad fall.

Stephen: I have two years to live.

Brian: Sorry?

Stephen: It does sound odd when you say it aloud.

This actually reminded me of a moment in my own life. About 10 years ago, I showed up late for work because I was visiting a friend in the hospital. My manager, a good guy, came around and, as a prelude to getting to the business at hand, the stupid tasks we needed to complete before shipping a product, asked, with a smile, how my friend was—and he was met with my wrecked face and voice. My friend had had a stroke; he was in a coma; he wouldn’t recover. The movie captures that awkwardness when we’re met with that blunt reality of finality. When life doesn’t continue.

But here life continues.

Or more

That’s astonishing, isn’t it? Lou Gehrig, for whom the disease is named, played a full season in 1938 but managed only eight games in 1939 before being diagnosed with ALS. He died in June 1941. He was an exceptional athlete and one of the strongest men in the game—nicknamed “The Iron Horse”—but he only lasted two years after diagnosis. Hawking keeps on.

Isn’t this something to be celebrated? In the movie, to Jane, it’s simply annoying. I think she even implies that she only got on board because the marriage was supposed to be a two-year stint. “This will not be a fight, Jane,” Hawking’s father, Frank (Simon McBurney), says early in the movie. “This will be a very heavy defeat.” But it isn’t—at least not the way they anticipate. It’s a heavy defeat not in the exceptional but in the quotidian. Which is the thing that outdoes most of us.

Here’s the oddity: the film focuses way too much on her but it’s still unfair to her. Because we don’t see all the work that goes into caring for their two, then three kids, as well as Hawking. There he is in bed: happy, clean. But how did he get in bed? How did he get clean? How did he go to the bathroom? Who wiped him?

Instead, there’s Jane, angry, and Charlie Cox, and all that sexual tension. While she dallies in a tent, Hawking goes off to France for a conference, contracts pneumonia and is near death. The doctors recommend shutting off his life support, but Jane, spent, with another iron in the fire, still refuses. So: tracheotomy and slow recovery and the loss of his speech and the voicebox with the American accent. He also finally gets round-the-clock nursing care in the form of Elaine Mason (Maxine Peake), who exudes sexuality. It’s like a wave—whoosh—and it washes away what’s left of Jane and Stephen’s relationship.

Redmayne’s performance is superb, by the way. “At times,” Hawking has said, “I thought he was me.” Director James Marsh also directed “Man on Wire” and an episode of “Red Riding,” while screenwriter Anthony McCarten wrote “Death of a Superhero,” about a 15-year-old boy with a life-threatening illness. So it should work, shouldn’t it?

It doesn’t. It doesn’t have enough curiosity about the things Hawking is curious about. After a time, it stops looking up at the stars. The movie isn’t a fight, it’s just a very sad defeat.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)