Thursday December 06, 2012

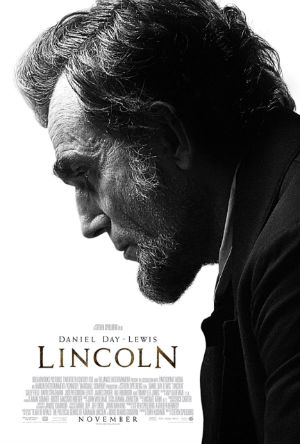

Movie Review: Lincoln (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

You know the saying that laws are like sausages—you don’t want to see them being made? Tony Kushner says, “Grow up.” Steven Spielberg says, “We’ll loin ya.” Their movie, “Lincoln,” is not only the greatest story ever told about the passage of a law—in this case the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which formally, legally abolished slavery—it’s a joy for anyone who cares about great acting, writing, and drama. It’s what movies should be.

In 1915, Pres. Woodrow Wilson called “The Birth of a Nation,” D.W. Griffith’s Confederate-friendly epic, “history written with lightning,” but I wouldn’t call this movie that. It’s history written as carefully as history should be. It’s well-researched and made dramatic and relevant. Abraham Lincoln (Daniel Day-Lewis), the most saintly of all presidents, isn’t presented here as a saint but as a smart, moral, political man, who, under extraordinary pressure from all sides, does what he has to do in order to do the right thing. His machinations aren’t clean. It takes a little bit of bad to do good. Progress is never easy. There are always slippery-slope arguments against it. Sure, free the slaves. Then what? Give Negroes the vote? Allow them into the House of Representatives? Give women the vote? Allow intermarriage? The preposterousness of where the road might take us prevents us from taking the first step. Then and now.

In 1915, Pres. Woodrow Wilson called “The Birth of a Nation,” D.W. Griffith’s Confederate-friendly epic, “history written with lightning,” but I wouldn’t call this movie that. It’s history written as carefully as history should be. It’s well-researched and made dramatic and relevant. Abraham Lincoln (Daniel Day-Lewis), the most saintly of all presidents, isn’t presented here as a saint but as a smart, moral, political man, who, under extraordinary pressure from all sides, does what he has to do in order to do the right thing. His machinations aren’t clean. It takes a little bit of bad to do good. Progress is never easy. There are always slippery-slope arguments against it. Sure, free the slaves. Then what? Give Negroes the vote? Allow them into the House of Representatives? Give women the vote? Allow intermarriage? The preposterousness of where the road might take us prevents us from taking the first step. Then and now.

Nobody does it better

I once said of Jeffrey Wright’s Martin Luther King, Jr., that no one would ever do it better; I now say the same of Day-Lewis’ Lincoln. He only has to talk about his dreams to his wife, Mary Todd (Sally Field), with his stockinged feet up on the furniture, a kind of languid ease in his long-limbed body, and I’m his. He only has to quote Shakespeare one moment (“I could count myself a king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams”), and, in the next, ask Mary, in a colloquialism of the day, “How’s your coconut?” and I’m his. I remember when I was young, 10 or so, and we were visiting my father’s sister, Alice, and her husband, Ben, and when we had to leave I began to cry. Because I didn’t want to leave Uncle Ben. I liked being near him. He had a calm and gentle spirit that I and my immediate family did not. It felt comfortable to be around. I got that same feeling from Daniel Day-Lewis here. How does he do that? How do you act a calm and gentle spirit?

His Lincoln exudes charm. During a flag-raising ceremony, he pulls a piece of paper from his top hat, says a few quick words, then looks up with a twinkle in his eye. “That’s my speech,” he says, and returns the paper to his top hat. He gives his cabinet, reluctant to spend political capital on another go at the 13th amendment, which the House failed to ratify 10 months earlier, a primer on the legal difficulties of the Emancipation Proclamation. If slaves are property, then… If the Confederacy is not a sovereign nation but wayward states, then… Finally he apologizes for his long-windedness: “As the preacher said, I would write shorter sermons but once I get going I’m too lazy to stop.” He says it with a twinkle in his eye. His stories are there for purposes of instruction and/or distraction. Maybe he does it to distract himself. In the war room late at night, waiting on word about the shelling of Wilmington, Va., a blanket around his shoulders and a cup of coffee in his hand, he launches into an anecdote about Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, and Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton (Bruce McGill), loudly objects. “You're going to tell one of your stories! I can't stand to hear another one of your stories!” He leaves. Too bad. He missed a great story. Added bonus: You get to hear Day-Lewis, an Englishman, acting as Lincoln, an American, imitating an Englishman.

If this Lincoln is human-sized so is the presidency itself. Petitioners line up outside Lincoln’s office to ask for favors. His cabinet is full of men who think they should be president and aren’t reluctant to share their opinions. His wife has her complaints (their son, Willie, dead now three years), his son Robert has his (he wants to leave law school for the war), Negro soldiers have theirs (they’re getting paid $3 less per month than white soldiers). Both political extremes mock him. Abolitionists consider him cautious and timid, a lingerer and a buffoon, while the Northern Democrats malign him as a tyrant enthralled to the Negro. They thunder about him in Congress. “King Abraham Africanus!” they cry. A president considered too conciliatory by friends and an African tyrant by foes? Plus ca change.

Peace v. Freedom

Ultimately “Lincoln” is about the choice between peace (for all) and freedom (for a few). “It’s either this amendment or the Confederate peace,” Secretary of State William Seward (David Strathairn), tells the president. “You cannot have both.”

Almost everyone pushes Lincoln toward peace even as he moves, in his methodical, searching manner, toward freedom. He gave himself the power during war to proclaim all slaves free, but what happens in peace? Won’t slavery still be legal in the South? Couldn’t the Civil War just happen all over again over the same issue?

The 13th amendment has already passed in the Senate and it’s just 20 votes shy in the House. So early in January 1865, even as he sends moderate Republican Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) to Virginia to set up a potential peace conference with secessionist delegates, Lincoln hires, or has Seward hire, three scallywags (read: lobbyists), gloriously headed up by James Spader as W.N. Bilbo, to more or less buy the votes of lame-duck Democrats, losers of the 1864 election, who have nothing to lose and gainful employment to gain.

That’s the true drama of the movie. Can Lincoln, in the midst of pulling back the South to the Union, hold together enough of the disparate elements that remain to abolish slavery at the federal level before the South returns and gums up the works again? We get a few key moments, several dramatic scenes. The Northern Democrats attempt to goad thundering abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones), who doesn’t suffer fools gladly, into proclaiming on the House floor that he believes in the equality of races (anathema at the time) and not just equality before the law.

You know all of those “100 Greatest Movie Insults” compilations on YouTube? They need an update. This is Stevens’ rejoinder:

How can I hold that all men are created equal when here before me stands, stinking, the moral carcass of the gentlemen from Ohio, proof that some men are inferior, endowed by their maker with dim wit impermeable to reason, with cold, pallid slime in their veins instead of hot, red blood. You are more reptile than man, George! So low and flat that the foot of man is incapable of crushing you.

What fun. The language here is beautiful. I also like it when Lincoln calls his cabinet “pettifogging Tammany Hall hucksters.” We need to bring that back: “pettifogging.” We need to bring back erudite insults.

But the key scene in the movie contains no thunder, and the key man who needs convincing isn’t a Democrat; it’s Lincoln himself.

Self-evidence

As with the Ethan Allen story, it takes place in the middle of the night in the basement of the White House. Lincoln is about to send a message in Morse code about the “secesh” delegates, and ruminates out loud with several officers. Up to this point he’s been pursuing two paths, one leading to peace but not passage, the other pointing to passage but not peace, and this is the point where the paths diverge and he has to choose which to walk on. He begins down the path of peace: bring the delegates to Washington. But before the message is sent, he engages the two men in conversation.

One of them, it turns out, is an engineer. Lincoln asks him if he knows Euclid’s axioms and common notions, and then regales them with the first: Things which are equal to the same things are equal to each other. “That’s a rule of mathematical reasoning,” he says. “It’s true because it works. Has done and always will be.” He seems to be talking out loud. But there’s a moment, an epiphanic “huh,” when Lincoln realizes the point he’s talking toward:

In his book, [huh] Euclid says this is self-evident. You see, there it is, even in that 2,000-year-old book of mechanical law: It is a self-evident truth that things which are equal to the same things are equal to each other.

The beauty of the scene? Kushner and Spielberg draw no line to the Declaration of Independence. They assume we’re already drawing that line ourselves. They assume it’s self-evident. They just give us Daniel Day-Lewis saying “Huh.”

At which point he rescinds the order sending the peace delegates to Washington, and thereby changes history.

To the ages

“Lincoln” isn’t all glory. The screenplay by Tony Kushner attempts to demythologize history, the presidency and Lincoln, but Spielberg, fore and aft, can’t contain his myth-making tendencies.

In the beginning, sitting on a raised platform, Pres. Lincoln engages four soldiers, two black and two white, and seems halfway to Memorial already. Three of the four soldiers have the Gettysburg Address memorized already, as if they were 20th-century schoolkids (Dan Roach and myself in fifth grade) rather 19th-century soldiers. We hear tinkling music as if in a Ken Burns documentary. It’s all rather unnecessary. We could’ve begun with Lincoln’s bad dream and stockinged feet and gotten on with it.

Then there’s the ending. Spielberg has always had a problem with endings. From behind, with music swelling, we watch Lincoln leave the White House, on April 14, 1865, late for Ford’s Theater. “Not a bad end,” I thought. But it’s not the end. We go to the theater, but it’s a different theater, one his son Tad is attending, which suddenly closes its curtains to announce the awful and inevitable. Then there’s a deathbed scene: Mary wailing, the doctor declaring, blood on the pillow, someone saying, as someone maybe said or maybe didn’t, “Now he belongs to the ages.” The end? No. Spielberg has to include the second inaugural: “With malice toward none, with charity to all…” Meanwhile I sat in my seat, feeling not very charitable.

But those are my only complaints about “Lincoln.”

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)