Friday February 17, 2012

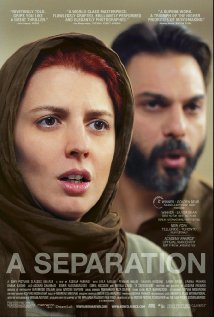

Movie Review: A Separation (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Our sympathies keep changing in “A Separation” in a way that reminded me of life.

Initially, Simin (Leila Hatami) seems the sympathetic one, at least to western eyes, since she wants out of Iran for both herself and her daughter, while her husband Nader (Peyman Maadi) seem stubborn and awful for refusing to go. When Simin does leave, she goes, not out of the country but across town, to stay at her mother’s, leaving Nader to care for their daughter, Termeh (Arina Farhadi), who’s 11 and smart, as well as his father (Ali-Asghar Shahbazi), who is old and suffering from Alzheimer’s.

But we also have sympathy for Razieh (Sareh Bayat), whom Nader hires to help in his wife’s absence. She’s pregnant; she has her own daughter, Somayeh (Kimia Hosseini), an adorable, big-eyed thing, to worry about; and now, for 300,000 rials a day (about US$26.50), she has to look after Nader’s father, who wets himself, and who may wander off at any moment to get the newspaper at the newsstand down the street. Wetting himself, and not being able to change himself, is the big problem. She’s unsure whether it’s a sin for her to be this close to a man she doesn’t know, but there’s a kind of Islamic hotline she can call to plead her case. She does, successfully, but it’s really more than she bargained for. So she asks Nader: Could her husband, Hodjat (Shahb Hosseini), take the job instead?

But we also have sympathy for Razieh (Sareh Bayat), whom Nader hires to help in his wife’s absence. She’s pregnant; she has her own daughter, Somayeh (Kimia Hosseini), an adorable, big-eyed thing, to worry about; and now, for 300,000 rials a day (about US$26.50), she has to look after Nader’s father, who wets himself, and who may wander off at any moment to get the newspaper at the newsstand down the street. Wetting himself, and not being able to change himself, is the big problem. She’s unsure whether it’s a sin for her to be this close to a man she doesn’t know, but there’s a kind of Islamic hotline she can call to plead her case. She does, successfully, but it’s really more than she bargained for. So she asks Nader: Could her husband, Hodjat (Shahb Hosseini), take the job instead?

Nader is willing, even grateful, but surprised when it’s still Razieh who shows up the next day, and the next. Something about her husband being in jail? Something about creditors? Nader is even more surprised, and angered, when he comes home early one day to find no one at home and his father tied to the bed. Initially he thinks he’s dead. He’s not, but he’s bruised. And really who would do such a thing? And where is the day’s money Nader left on the dresser? And it’s at this point that Razieh returns, with her daughter, and with nothing like shame or guilt on her face. Who is this woman? How could she do such a thing to his father? And still she demands her day’s pay? Why doesn’t she get out of his apartment. Out! Out!

Yeah, so what if Razieh slipped when he shoved her out the door. Really? She miscarried? That’s awful. From the shove? That doesn’t seem...? She and her husband are pressing charges? For murder?

Poor Nader.

God, where the fuck is his wife during all of this?!

The relativity of all of this is key. The lack of absolutes is key. The small lies that occur daily, or the big lies that occur when our backs are to the wall, or the information withheld to make one’s case better, all of these things are key. “A Separation” begins inconclusively before an unseen judge, and it ends—beautifully—in a kind of purgatory of inconclusiveness, and in the middle ... is anything resolved? The more both parties go to find justice, the more injustice they find. The more control they attempt to exert, the more things fall apart. “A Separation” isn’t just about the separation of a man and a wife; it’s about a separation from truth, from respect, and maybe from love.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)