Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

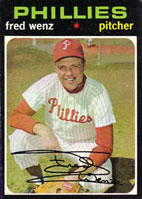

Where Have You Gone, Fred Wenz?

Reflections on the 1971 baseball card you never wanted but always got

In the 1950s the Topps company began using baseball cards to sell bubblegum, rather than vice-versa, but by the time I began collecting in 1971, at the age of 8, the gum was an afterthought: a thin, pink rectangle, sometimes coated with powdered sugar, increasingly not, with corners so sharp the thing could be used as a ninja weapon. Whenever I popped it into my mouth—standing in the parking lot of our local minimart, Little General on 54th and Lyndale in south Minneapolis—I’d let it soften before chewing to avoid scraping the insides of my cheeks. Just as often I’d toss it in the air and watch it shatter on the asphalt. It’s not like I didn’t want gum. I’d pay five cents, half the cost of a baseball pack, for a long rope of purple Bubs Daddy. I just didn’t want that gum. I didn’t know what gum was but I knew it wasn’t supposed to shatter.

If modern baseball cards were an accident of marketing they were a brilliant accident. They appealed to boys on so many levels:

- They represented something we admired

- We got to collect them.

- Since we never knew what we were going to get, there was mystery and anticipation.

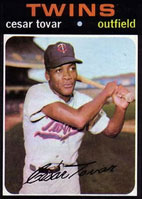

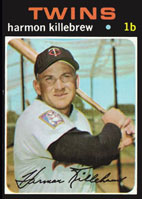

I anticipated and coveted Minnesota Twins in particular: Harmon Killebrew, Tony Oliva, Cesar Tovar, Rod Carew. Even the lowliest of Twins (Tom Tischinski) had a magic that future Hall of Famers (Jim Palmer) did not. Something about that Minne/St. Paul patch on the sleeve. Something about the crossed “TC” on the cap. When a Twin showed up behind a Dennis Menke or a Jerry McNertney, it was like the sun making an appearance from behind a bank of clouds.

There were 756 cards in the 1971 Topps series, so the odds of getting one of those 25 Twins in a pack of 10 were pretty slim. But one player kept worsening the odds.

I’m not sure when my friend Dave and I noticed we kept getting Fred Wenz but we definitely noticed. At first it was annoying. Then it got funny. Finally, and possibly for the first time in our lives, we were left with nothing but conspiracy theories. We talked about how the Topps company trucked all the packs with Fred Wenz to Minneapolis and all the packs with Harmon Killebrew to Philadelphia. We talked about how Topps manufactured 10 times as many Fred Wenzes as Harmon Killebrews to keep us buying. We talked about how Fred Wenz was probably related to the president of Topps. What else could explain his ubiquity? Because there he was again!

When I finally turned over his card to see if there was anything worthwhile about him I was startled to find ... pitching stats? Wasn’t Fred Wenz a catcher? On his card he was certainly crouched like a catcher. This merely added to his absurdity. Didn’t Fred Wenz know which position he played?

His career stats were pretty skimpy: 31 games, 42 innings pitched. A box in the middle of the card muddied rather than clarified matters:

FIRST YEAR IN PRO BALL — 1959

FIRST GAME IN MAJORS — 1968

Since I didn’t differentiate between “Pro Ball” and “Majors,” I tried to wrap my 8-year-old mind around a player who spent nine years on Major League rosters without ever getting into a game.

Then there was the absurdity of his name. Just eight letters, two syllables, boom boom and out. It’s the cup of coffee of baseball names. So is Mel Ott, I suppose, but “Ott” ends on the hard consonant and feels strong. “Wenz” ends with a kind of soporific collapse. Wenzzzzz. Other players had musical names (Cesar Tovar), or stolid and majestic names (Harmon Killebrew), but Fred Wenz, who kept showing up, was stuck with this limp noodle of a name. Could a crappy player ever be named Harmon Killebrew? Could a great player ever be named Fred Wenz?

I don’t think we planned to do what we did. I think we were just goofing around, as boys do after a baseball-pack-buying binge at Little General, and somehow wound up on the Bryant Avenue bridge overlooking Minnehaha Creek. We were probably still chewing the hard, pink gum that came with the packs, and by this point, particularly in the cold weather, the gum was probably getting a little tough. So we spit it out toward the creek 100 feet below. Most of the creek was still frozen and snowed over, but there was one small patch, an ice hole, where we could see the dark waters rushing by. We tried to spit the gum into this hole.

Then it became a game. We grabbed what we could find—twigs, pebbles—and tried to drop them into the hole, too. But it was early spring, most everything was still covered with snow, and projectiles were hard to find.

Then Dave came up with a brilliant idea: Fred Wenz.

This would be trickier than pebbles or gum. This would require dexterity. Dave took off his gloves, leaned over the cold metal railing, and flicked the Fred Wenz card like a Frisbee, so that it arced away from and then back toward the ice hole. Missed! It stuck at an angle in the snow.

My turn. I was two years older than Dave, shorter, and more afraid of heights, so I probably didn’t lean out as far as he did. I didn’t come as close, either.

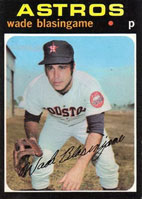

Fred Wenz began the game but I don’t think running out of him ended the game. I think we went with back-ups: the Wade Blasingames and Gene Brabenders and Dick Suches of the world. I hated the Baltimore Orioles, who were forever sweeping the Twins in the playoffs, so a few Orioles probably sailed off the bridge, too. Did Frank Howard? He was often second on the “A.L. Home Run Leaders” card to Harmon Killebrew. But on the 1971 card he had actually surpassed Killebrew. So long, Four Eyes.

Before long the creek was studded with baseball cards but we never managed a hole-in-one. The hole was obviously too small. So for a time we tried to widen it with snowballs and ice chunks and anything else we could find. Soon the creek, snowed-over and pristine when we arrived, looked like a battlefield, and afterwards, in my bedroom, I felt bad about all of those cards lying stuck in the snow. I had a fear of breaking through the ice of Minnehaha Creek and being swept away. Wouldn’t this happen to the cards once the ice melted? They’d get swept over Minnehaha falls, into the Mississippi river and down to the Gulf of Mexico. Forgotten.

The real Fred Wenz got swept away that spring. Before the season even started he was cut by his team, the lowly Philadelphia Phillies, and no one else picked him up. The year we kept getting his card was a year he never even played.

Is that why he’s smiling on the card? Was it the smile of a guy who had nothing to lose? Had he told the teammates “Maybe I’ll make the team as a catcher,” and smiled at their laughter, just before his photo was taken?

Fred Wenz remained an in-joke between Dave and I long after we stopped collecting baseball cards, a metaphor for the thing we never wanted but always got, but I’m older now and I identify with the man more. He spent nearly a decade making it to the bigs but at least he made it. He remained there for three years, head barely above water, with Boston and Philly. He appeared in 31 games, pitched 42.1 innings, struck out 38, walked 25. He was 3-0 lifetime, with a 4.68 ERA.

When we’re young we throw things away but as adults we just try to keep our heads above water. Once a promising prospect with the nickname “Fireball,” it came down to this: spring training in Florida, crouching in the sun for the Topps photographer, a brave smile.

—April 6, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard