Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

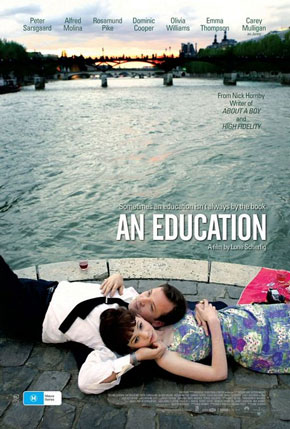

An Education (2009)

WARNING: COMING-OF-AGE SPOILERS

You could say Nic Benns’ brilliant title graphics are at odds with this story.

“An Education” is about a smart girl, Jenny (Carey Mulligan), raised by careful, working-class parents in post-World-War-II England, who, when she’s 16 going on 17, and Oxford is in sight, gets involved with an older, wealthier man and almost chucks it all away because his life is so much more interesting than her life of Latin, math and cello-playing. “My choice is to do something hard and boring for the rest of my life or go to Paris and have fun!” she says.

Then there are the title graphics. Backed by the bouncy, piano-heavy, early rock n’ roll beat of Floyd Cramer’s “On the Rebound,” animated drawings of books shift into diagrams of microscopes, which change into cells dividing and DNA patterns and music notes, and on and on, subject by subject. Hard and boring? Education never looked so fun.

It’s 1961 and Jenny’s a girl on the cusp. She’s cute, with deep dimples on fresh cheeks, and she’s filled with over 10 years of education that she doesn’t quite know what to do with yet. She’s more mature than her classmates, savvier than parents and teachers. She’s interested and interesting but with an air of What’s it all about, Alfie?

Enter David (Peter Sarsgaard), who pulls up in his Bristol car while she and her cello are waiting for the bus in the rain. First he disarms her with forthrightness (he knows she’s not supposed to accept rides from strange men...), then with misdirection (...but he’s a music lover and he’s worried about her cello), and finally charm. The boys in her school are tongue-tied around her, but this man—this man—makes her laugh.

He sends flowers. They meet again and he proposes a Friday-night Ravel concert with dinner afterwards. She says there’s no way her parents, particularly her no-nonsense father, Jack (Alfred Molina), will allow it. But David shows up and charms them, too. “I didn’t know you had a sister, Jenny,” David says, as he kisses her mother's hand. Check out Jenny’s reaction. Did he just say that? Did her parents just buy that? Can you really get away with that?

Much of the movie is learning just how much one can get away with. At the concert they meet David’s friends, Danny and Helen (Dominic Cooper and Rosamund Pike), and attend dinners and nightclubs and auctions. They make weekend trips to Oxford and Paris. In her first encounter with Helen—a tall blonde, tres chic, done up almost like Deneuve before Deneuve—they’re waiting to check their coats and Jenny drops a few lines of French, as I’ve done. Helen stares at her placidly:

“What’s that you said?” “I said it was too expensive.” “But those weren’t the words you used.” “I was speaking French.” “Oh.”At first I thought Helen was mocking Jenny’s schoolgirl pretensions, her need to trot out her French; but it turns out Helen is as dumb as a stump. At the same time, she’s not mean. She’s rather sweet.

Even as Jenny's caught up in the whirlwind of David’s playboy lifestyle, she gets clues about him. Some seem positive: He has Negro friends, or at least clients, in 1961. Some seem icky: the odd talk he instigates before sex. Some reveal the chasm between them: At Oxford, David says to the group, “I spent three years here,” to which Danny responds, “Oh God.” The institution she’s spent her life trying to get into is, to these folks, simply a dreadfully dull place.

Is that why they need her around? Because life is so dreadfully dull and they need fresh eyes with which to view it? She has a gas bidding for a pre-Raphaelite painting, and so do they, because she has such a gas. “That’s why you’re here,” David tells her later. “To save us from ourselves.”

Other shoes drop. On the way back from Oxford the two men go to an open house and steal a beautiful, framed map. “Liberating it,” they call it. She finds out David’s real job: He moves Negro families into neighborhoods, gets the scared old ladies to sell to him cheap, then moves the Negroes out and reinflates the price. It’s a brilliant scheme, playing on the prejudices of the era (and probably this era), but it’s so awful. He's a con man; charming, yes, but a con man. But this shoe doesn’t drop hard enough. Jenny now knows he cons old ladies and her parents but somehow she thinks she's immune.

Amidst this whirlwind, her studies falter, Oxford dims, and her dowdy coats and hair are replaced by sophisticated, swept-up, elegant things. In subtle ways, she becomes dismissive of teachers and parents, who aren’t in on the con. She leaves school altogether—with her father’s blessing—when David proposes marriage, but this turns out to be the biggest con of all. His name isn’t David Stewart but David Goldstein, and he’s married with children. When Jenny arranges to surreptitiously meet the wife (Sally Hawkins from “Happy-Go-Lucky”), the wife immediately figures out who and what she is. “You’re not in a family way, are you?” she asks. “Because that’s happened before.”

There’s a heart-breaking scene where her father talks to her outside her bedroom door. He had a very regimented life set up to get her into Oxford, but he succumbed, perhaps even more than her, to David’s charms, dazzled by the possibilities of her life away from all this: from the penny saved: from the bit-by-bit; from the pinched existence. The earlier Oxford trip had been greased by a promised meeting with C.S. Lewis—“Clive,” as David pretended to call him—and in a bar we see David signing Jenny’s copy of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe as “Clive,” with everyone, including Jenny, amused. Now outside the bedroom door, the father talks about listening to a radio program the previous week that mentioned how C.S. Lewis left Oxford in 1950, and how he thought, “Well, they’ve got that wrong. My Jenny...” The thought trails. He believed his daughter over the radio. His lack of bitterness at being conned, his solicitude for her in her heartbreak, makes the scene extra poignant. "All my life I've been scared," he admits. "And I didn't want you to be scared." He leaves her tea and biscuits.

“An Education” is based upon the memoir by Lynn Barber, which was adapted by Nick Hornby (“High Fidelity”; “About a Boy”) and directed by Lone Scherfig (“Italian for Beginners”; “Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself”). It’s an impeccable film, beautifully acted, wonderfully written, hilarious at times and sad at times. Everything feels exactly right within the confines of its story. But it doesn't resonate much beyond that. Most of us already know the lessons Jenny needs to learn. Plus the movie leaves unanswered its most fundamental questions. During her engagement, Jenny tells her school’s headmistress (Emma Thompson, in a killer cameo), “It’s not enough to educate us any more, Miss Walters, you’ve got to tell us why you’re doing it.” It’s a good question, but Miss Walters, and the movie, never really answers it. Instead, after Jenny’s been derailed, she spends the rest of the movie struggling to get back on the rails. To what end? Because that's what we do? As people? In this society? What's it all about, Jenny?

The last line does resonate. We see Jenny, finally at Oxford, biking with a classmate, and we hear her in voiceover: “One of the boys I dated—and they were boys—suggested we go to Paris, and I said I'd always wanted to see Paris. As if I'd never been.” It suggests so much. A pretense to innocence and enthusiasm that’s no longer hers. A time before she was conned. A kind of con of her own.

—November 9, 2009

© 2009 Erik Lundegaard