Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

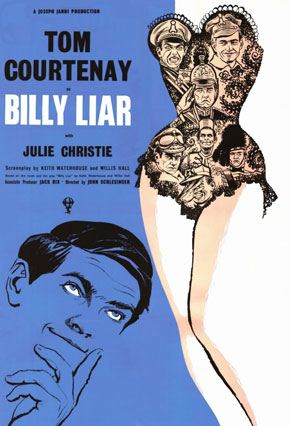

Billy Liar (1963)

I first encountered this story in its 1978 U.S. television incarnation, "Billy," starring Steve Guttenberg. One of Billy's fantasies, I remember, involved Suzanne Sommers of the new hit comedy "Three's Company," who, while not my first adolescent fantasy girl, didn't seem a bad choice. I don't think the show lasted 13 episodes.

Written by:

Willis Hall

Keith Waterhouse

(Based on the novel by Waterhouse and the play by Hall and Waterhouse)

Directed by:

John Schlesinger

Starring:

Tom Courtenay

Julie Christie

Leonard Rossiter

Wilfred Pickles

Mona Washbourne

Ethel Griffies

Finlay Currie

BAFTA Nominations:

Best Film

Best British Film

Best British Actor

Best British Actress (Christie)

Best British Screenplay

Best British Cinematography (B/W)

Quote:

“Count five and tell the truth.”

Billy Liar is on another plane altogether. It's a simple story with an ending you anticipate; but there are intricacies in the various relationships, and the film ultimately says something meaningful about the average man's place in the middle of the 20th century.

Billy Fischer (Tom Courtenay) is the quintessential dreamer. He lives in a northern English town with his parents and grandmother but dreams of great things. In his bed, and marching off to work at a funeral parlor, he dreams of a fictional country called Ambrosia, where he is all things to all people. Even his conversation is peppered with dreams, which he attempts to pass of as reality. He claims he's moving to London to be a scriptwriter for the comedian Danny Boon (Leslie Randall), when Boon hardly knows him. He claims he's finishing a novel which he hasn't started. Two different women are engaged to him and he's in love — or should be in love — with a third. Reality, being what it is, has a way of intruding on this dreamworld. Parents hector him, colleagues mock him. Then there's the business with the funeral parlor calendars that he was supposed to mail out to customers. How to get rid of the evidence? His solution is a brilliant metaphor for his life: he literally throws months and years down the toilet.

It would have been easy to make Billy an entirely sympathetic or comic creation but Tom Courtenay and director John Schlesinger know better. Their Billy is, at times, comic and sympathetic, at times creepy and exasperating. His response to his grandmother's death is self-involved and unsympathetic. His Ambrosia fantasies, while WWII-era Britain, give off whiffs of Fascism, as if Mussolini more than Churchill were his role model.

(These fantasies also seem odd for a young man in early '60s Britain. Wouldn't they be his parents' fantasies?)

Between complaining parents and a complaining boss (Leonard Rossiter - who, ironically, would come to represent the suffocated employee in the great '70s BBC comedy "The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin"), Billy has one ray of hope: Liz (Julie Christie), the town free spirit. When we first see her I assumed she was another of Billy's fantasies. But at a club that evening she waves him over, cuts through his lies, refuses to play the dating game, and — shock! — professes love. By the end of the evening she offers escape: a midnight train-ride to London. It's fascinating to watch his parents reaction to this. As it becomes a distinct possibility, they make arguments against it. Clearly they want him to remain behind. And clearly Billy wants to remain behind, too. We're watching a complex, dysfunctional family, whose neuroses are so intermingled it's difficult to untangle them. It's a nice ending even though we anticipate it.

Unfortunately there's no way Liz falls for Billy in the first place. She's too free-wheeling to love someone who represents stagnation.

Throughout Billy Liar there's beautiful black-and-white cinematography from Denys N. Coop and unobtrusive acting from the entire cast, and, of course, a star-making turn from Christie. And there's no escaping the fact that there's a bit of Billy in each of us. May we all have the courage to take the midnight train to London.

—November 22, 2002

© 2002 Erik Lundegaard