Thursday May 25, 2023

Vida Blue (1949-2023)

Charlie Finley was an all-world huckster who had some fun ideas about shaking up the staid old game: those garish, glorious, green-and-gold A's unis; paying his players to grow long hair and facial hair during the hippy-ish early 1970s; manufacturing Old Timey nicknames. All of that was fun. He had shitty ideas, too: orange baseballs, the DH, but I think the worst of them relates to that third fun idea. He'd done well enough with Jim “Catfish” Hunter and John “Blue Moon” Odom, both great, both pure grift, but then he tried to impose the nickname “True” on one of his other young pitchers, and that pitcher balked at the idea. As he should have. Because he already had one of the most perfect names in baseball history. To be honest, I worry a little about Charlie Finley—that when presented with this almost perfect baseball name, nearly a double unique, he didn't see it. He wanted to fuck it up with a false, punny “True.” He didn't see the perfection that was already there in Vida Blue.

For the first half of 1971, when he was just 21 years old, Vida Blue was nearly perfection. He may have been the first superstar to emerge once I became a fan. Everyone else was already there when I showed up: Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Frank and Brooks Robinson, Harmon Killebrew, Tony Oliva, even the fairly youthful Johnny Bench. But Vida Blue was not there and then, in the spring and summer of 1971, he was everywhere. He was an event.  He was such an event they held a Vida Blue Day for him ... in Minnesota. Twins owner Calvin Griffith was a sad, slow huckster compared to Charlie Finley, but he knew what people wanted, and he knew in the summer of 1971 they wanted Vida Blue. And so for a twi-night doubleheader, the Twins honored the opposing pitcher. In my memory, if you wore a piece of blue clothing you got in for half price, but that doesn't make much sense. Calvin wouldn't take money from Calvin's coffers. No, what you got, if you wore anything blue—and the Twins' promo ad mentioned any apparel, including “suits, dresses, hot pants...” which gives you a sense of the divide in America at the time, when men still wore suits to ballgames while women wore hot pants—what you got, from Calvin on Vida Blue Day at Met Stadium, was a commemorative button, “an attractive blue button,” the ad said, with the following verse:

He was such an event they held a Vida Blue Day for him ... in Minnesota. Twins owner Calvin Griffith was a sad, slow huckster compared to Charlie Finley, but he knew what people wanted, and he knew in the summer of 1971 they wanted Vida Blue. And so for a twi-night doubleheader, the Twins honored the opposing pitcher. In my memory, if you wore a piece of blue clothing you got in for half price, but that doesn't make much sense. Calvin wouldn't take money from Calvin's coffers. No, what you got, if you wore anything blue—and the Twins' promo ad mentioned any apparel, including “suits, dresses, hot pants...” which gives you a sense of the divide in America at the time, when men still wore suits to ballgames while women wore hot pants—what you got, from Calvin on Vida Blue Day at Met Stadium, was a commemorative button, “an attractive blue button,” the ad said, with the following verse:

Rose are red

My clothes were blue

When I was there

To see Vida Blue

Even at age 8, I was like “That's not a rhyme. Blue and blue? That's just the same word.” But we went, wore blue (without trying), got one of those buttons, and saw the Twins win both games against the eventual division winners. Actually, no, we didn't see the victories. I don't know why I still remember this but I do. We arrived late to the first game, missing out on Harmon Killebrew's pinch-hit grand slam in the Twins 9-4 victory, then we left before the end of the second game (“We gotta beat the traffic!” --Frank Costanza and my father), so missed out on George Mitterwald's walk-off homerun against Vida Blue with two outs in the bottom of the 9th as the Twins won 2-1. Two amazing games and we missed out on both big blows. This is why, for the longest time after I became an adult, I never left a game early.

In that second game, Twins pitcher Hal Haydel got the W for his 9th-inning relief work (one of six Ws in his career), while Vida got the L for the game and went a mere 23-7 on the season. He would wind up 24-8 with a 1.82 ERA, 301 strikeouts to 88 walks in 312 innings pitched, and he would win the Cy Young and the MVP as a 21/22 year old. But the real story was his first half when he went 17-3 with a 1.42 ERA, 17 complete games and six shutouts. Again, that's the first half of the season. He seemed on pace to win 30. He seemed perfection. I'm looking at his game logs for the season and he actually started out poorly, on April 5, giving up 4 runs, 1 earned, in 1 2/3 innings against the lowly Washington Senators. Then he pitched a six-inning rain-shortened shutout against the Royals, striking out 13(!); pitched a complete game shutout of the Brewers; pitched a complete game victory against the ChiSox, and kept going. By the end of May he'd won 10 games (10!), and was on the cover of Sports Illustrated. By the end of August, he was on the cover of Time magazine under the heading “New Zip in the Old Game.”

In that second game, Twins pitcher Hal Haydel got the W for his 9th-inning relief work (one of six Ws in his career), while Vida got the L for the game and went a mere 23-7 on the season. He would wind up 24-8 with a 1.82 ERA, 301 strikeouts to 88 walks in 312 innings pitched, and he would win the Cy Young and the MVP as a 21/22 year old. But the real story was his first half when he went 17-3 with a 1.42 ERA, 17 complete games and six shutouts. Again, that's the first half of the season. He seemed on pace to win 30. He seemed perfection. I'm looking at his game logs for the season and he actually started out poorly, on April 5, giving up 4 runs, 1 earned, in 1 2/3 innings against the lowly Washington Senators. Then he pitched a six-inning rain-shortened shutout against the Royals, striking out 13(!); pitched a complete game shutout of the Brewers; pitched a complete game victory against the ChiSox, and kept going. By the end of May he'd won 10 games (10!), and was on the cover of Sports Illustrated. By the end of August, he was on the cover of Time magazine under the heading “New Zip in the Old Game.”

In the second half, sure, not quite perfection. His ERA rose by a run, to 2.40, and he went 7-5, but there were games that should've been wins. On July 9 against the Angels, he pitched 11 shutout innings, struck out 17 and walked nobody but got the ND. (The A's won it 1-0 in the bottom of the 20th.) Two weeks later, he again went 11, striking out 11 and walking zilch as the A's won it in the bottom of the 12th. But yes, he must've been tiring. His last shutout was August 7 against the ChiSox, his 20th win. In the second half, he was very, very good, but not the Vida Blue of the first half. He was not a comet. But he was beautiful to watch.

Same for the rest of his career. After a season for the ages, he wanted a raise, Finley was penurious, Vida held out. A deal was finally struck ($14.7k —> $63k), but late, so Vida didn't make his first start until the end of May, and though he had a not-bad 2.80 ERA he went 6-10. The next year he won 20, then 17, then 22, as the A's became the only non-Yankees team to win three World Series in a row. In '76 Vida had an ERA of 2.35 and finished sixth in the Cy Young balloting, and was traded midseason to the New York Yankees. Except, whoops, no, another white man, Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, in perpetual battle with Finley, nullified the deal “in the best interests of baseball.” Back you go. He finally got away from Finley in '78, across the Bay to San Francisco, and became the first pitcher to start for both leagues in the All-Star Game. He lasted until the mid-1980s. Along the way there were drug problems. His career numbers are similar to Catfish Hunter's, but Catfish's rep was different, and Catfish came on the Hall of Fame ballot at the right time, so he got in. Blue, not. His rep was of not quite living up to the promise of that first half of 1971. But how could he? Comets streak across the sky, then disappear from view.

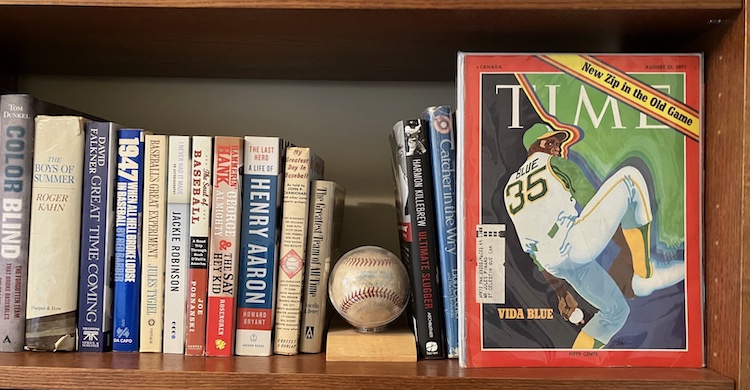

How much does Vida Blue mean to me? A kid who grew up rooting for another team in another state? One evening last November, after I'd returned home from New York City sick with COVID, I was involved in the usual late-night web searching, checking out this and that, and I wound up buying a comfort item for myself, something that just made me feel good. It was that August 1971 Time magazine with Vida Blue on the cover. It's been on my bookshelf ever since. It never doesn't make me smile.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)