Monday January 17, 2011

Review: True Grit (2010)

WARNING: FILL YOUR HAND WITH SPOILERS, YOU SON OF A BITCH!

There’s an irony to how well “True Grit” is doing at the box office—$126 million after four weeks, by far the Coens highest-grosser—because, and with deep apologies to cinematographer Roger Deakins, this is a movie that needs to be seen on DVD, and with the subtitles most definitely on. It’s not just that some of Jeff Bridges’ better lines are swallowed in a drunken rumble; there’s such richness to the language here that you don't want to miss anything. It’s so specific to time and place. Examples:

- You cannot have your way in every particular.

- I do not entertain hypotheticals; the world, as it is, is vexing enough.

- You have got very little sugar with your pronouncements.

People speak without contractions. They are precise. Their language is the language of those raised on the poetry of the King James Bible and little else:

- I felt like Ezequiel walking in the valley of dry bones.

- The author of all things walks with me and I have a fine horse.

- I will meet him later walking in streets of glory.

Most of this comes from the source material, Charles Portis’ 1968 novel, but the Coens knew enough not to mess with it, as Hollywood levelers and temperature-takers generally do. You could say this is true of all of the Coens' movies. Each has its own language specific to time and place. Darn tootin’.

In the Coens’ previous western, “No Country for Old Men,” they upended the genre’s tropes—the hero is killed off screen, the sheriff, plagued by nightmares, retires, while the villain keeps on keeping on—and, at first glance, “True Grit” feels like a corrective. It feels like a more traditional western. It is, but those boys are still upending the genre’s tropes.

In the Coens’ previous western, “No Country for Old Men,” they upended the genre’s tropes—the hero is killed off screen, the sheriff, plagued by nightmares, retires, while the villain keeps on keeping on—and, at first glance, “True Grit” feels like a corrective. It feels like a more traditional western. It is, but those boys are still upending the genre’s tropes.

For one, the story isn’t set in the “west.” It’s set in Arkansas, and the Choctaw Nation, which eventually became Oklahoma.

More, most westerns are about lawless places getting law. The line is clear: there’s chaos and then, generally after the hero arrives, there’s order. “True Grit” has a mix more familiar to modern sensibilities. Yes, people are killed, and outlaws light out for the territory; but the law still reigns.

Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld), a 14-year-old girl intent on avenging her father’s death, uses her lawyer as both cudgel and bargaining tool with everyone she meets. Won’t give her what she wants? She’ll sic her lawyer on you. Won’t tell her what she wants? Her lawyer can help you if you talk.

The first time she sees Rooster J. Cogburn (Bridges), drunkard and U.S. Marshall, he’s in a courtroom, the prosecution’s witness, and a defense lawyer, an almost strutting popinjay, who in anyone else’s movie would be flicked aside by the hero without much trouble, gets the better of him. Cogburn gets off some good lines, some unintentional, and you can see him playing to the crowd; but in the end the defense lawyer confuses him, makes him backtrack and ruins his case. Cogburn is the man with true grit, who has, Mattie says later, “great poise”; but this is a West where words matter as much as guns. Maybe more.

Let’s count the instances.

It’s Mattie’s words, along with the threat of her lawyer, which finagle $320 out of Col. Stonehill (Dakin Matthews) in a hilarious epic of bargaining; and it’s Mattie’s words, along with $100, which finally prompt Cogburn into pursuing Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin), her father’s killer; and it’s Mattie’s words, along with her own true grit, and the true grit of her horse, Little Blackie, fording the cold waters of the Mississippi into Choctaw territory, that allow her to accompany both Cogburn and a Texas Ranger, LaBoeuf (Matt Damon), who has been, in Mattie’s words, “ineffectually pursuing Chaney” for years for the murder (an assassination we would say now) of a Texas state senator.

Each of the main characters has his own vocabulary. Mattie’s words are always straightforward and come with a purpose: these words to get this done. Cogburn’s words are as rambling and shambling as he is. While they ride he goes on about his many wives, and in the midst of pursuit he makes promises to a dying man he doesn’t keep. It’s his very carelessness with words that allows the defense lawyer to run him in circles. LaBoeuf, meanwhile, makes grand, airy pronouncements like he’s his own PR rep. He’s forever in the midst of creating his own legend. “Never doubt a Texas Ranger,” he says at the end, when he finally makes good. “Ever stalwart.” He’s Hollywood a half century before Hollywood.

A word almost causes Cogburn and LaBoeuf to come to blows. “Sounds to me like you are being hoo-rahed by a little girl,” LaBoeuf says, and Cogburn can’t abide it. They accuse each other of being “bushwackers” and “brushpoppers,” and then they get on each other about the Civil War, only 11 years gone at this point, and the role of Capt. Quantrill, whom Cogburn served under, and who staged guerilla raids into neighboring territories—including an infamous raid on Lawrence, Kansas, in which 190 men and boys were executed. It’s a passing reference that suggests the vast history beneath the small story we’re watching. The Coens don’t bother tidying it up. You either know or you don’t, and if you don’t you can look it up. (I looked it up.)

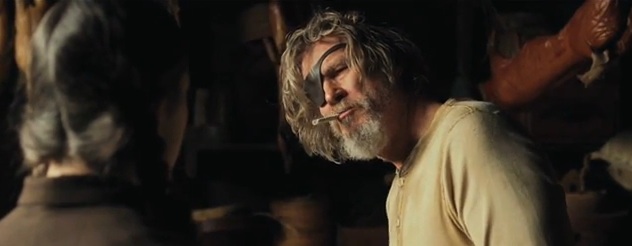

Do I need to say Bridges is monumental here? Cogburn’s vanity is on display in the courtroom and Bridges’ lack of vanity is on display everywhere else. He hangs out in his filthy longjohns, hair askew, bloated stomach threatening to burst past his buttons. His one visible eye looks confused at Mattie, annoyed at LeBoeuf, determined and deadly in a gunfight, and mean when he’s on a drunk. His comic timing is impeccable: “Well,” he says, dead bodies lying all around, “that didn’t pan out.”

No vanity for old men.

Steinfeld is a find, wonderfully forthright and proper and heroic; Damon suggests the hollow man LaBoeuf is, while Brolin is all low brow and grunts. He looks villainous and frightening but takes a while to get there.

When, after all that tracking and pursuit, Chaney is suddenly there in the creek in which Mattie has gone to get water, his reaction isn’t frightening at all; it’s dimwittedly friendly. “I know you,” he says, pleased. He can’t imagine why Mattie would be this far out in Choctaw territory. He sees it as a wonderful coincidence.

In the gang with which he hooked up, led by Lucky Ned Pepper (Barry Pepper), again, he’s not frightening. He’s the younger, stupider brother, forever ignored, disrespected and left behind. “Take me with you,” he whines, to no avail. One member of the gang is a short pug of a man who can only make animal sounds, but even he gets the respect denied Chaney. Mattie needles him for this and almost succumbs to the same fate as her father. Because this is when Chaney becomes frightening and villainous. He’s a man who takes out the disrespect he feels from more powerful people, such as Lucky Ned, on less powerful people, such as Mattie.

Each character surprises. Each has his own code. Cogburn, a U.S. Marshall, robbed banks in his youth, then dismisses it with a shrug and an excuse about never robbing a citizen. Lucky Ned, wearing the nastiest set of teeth in movies, and trading spittle-filled invective with Cogburn while pushing a boot into Mattie’s face, later acts the man of honor with her. Bargains are made—you do this and I’ll do this—but both Cogburn and Chaney go back on their word. Only Ned Pepper keeps his.

This is a rough and absurd world, an Old Testament world, where a laugh is followed by the horror of fingers being chopped off; where an anticipated showdown with a killer becomes the absurdist image of a bear toddling through the woods on a horse. (Should the Coens adapt John Irving? Or is he too New Testament for them?)

“You must pay for everything in this world, one way and another,” the adult Mattie narrates at the beginning of the film. “There is nothing free except the grace of God.” Indeed. Mattie gets her revenge—she’s the one who shoots and kills Chaney—but in that exact moment, when she (and we) should be enjoying her revenge, she begins to pay. The kick of the gun propels her into a deep pit she’s been twice warned about, and once she stops falling she looks up as if from the bottom of grave. (One can’t help but think of her sleeping accommodations at the undertaker’s place in Fort Smith.) Then she’s snake-bit, and Cogburn takes her to the nearest doctor, riding Little Blackie through the day and into the night, and into death. That’s the first way she pays. The second way is with her arm. She wanted to travel with these men and so becomes like them. LaBoeuf, the man full of hollow talk, loses part of his tongue; Cogburn, who likes to pull a cork, has a missing eye. She and her arm. No one gets through this life whole.

You must pay for everything in this world, one way or another.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)