Movie Reviews - 2020 posts

Monday June 27, 2022

Movie Review: Nomadland (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

In the beginning I thought of “Brokeback Mountain,” then, throughout, of John Mulaney. At the end, I was onto Nietzsche.

I’ll explain the middle part first.

In 2018, John Mulaney hosted the Film Independent Spirit Awards with Nick Kroll. That year, Frances McDormand was up for lead actress for her performance in “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri,” which she would go on to win (her third Spirit award), along with the Oscar (her second), and based on her character in the movie, and a certain vibe McDormand gives off, Mulaney said the following joke: “I bet a fun way to commit suicide would be to cut in front of her in line and then go, ‘Hey lady, re-lax.”

But before he says that, he says she’s great. And before he says that, he says, “Frances McDormand, you are no bullshit.”

That’s what I kept thinking throughout this film. Frances McDormand is great. And Frances McDormand is no bullshit.

Down the road

The movie begins in the place where “Brokeback Mountain” ended, with a survivor smelling and hugging the shirt of a loved one who passed. Fern (McDormand) is picking through the items in a storage locker in Empire, Nevada, a former company town of 700+ people working for US Gypsum, which the company closed in the wake of the Global Financial Meltdown of 2008-09. She’s deciding what to take with her and it’s not much. She takes a plate with a pink pattern around the edges—something you might see on your grandmother’s table. She seems unsure, and alone, and wholly vulnerable.

The movie begins in the place where “Brokeback Mountain” ended, with a survivor smelling and hugging the shirt of a loved one who passed. Fern (McDormand) is picking through the items in a storage locker in Empire, Nevada, a former company town of 700+ people working for US Gypsum, which the company closed in the wake of the Global Financial Meltdown of 2008-09. She’s deciding what to take with her and it’s not much. She takes a plate with a pink pattern around the edges—something you might see on your grandmother’s table. She seems unsure, and alone, and wholly vulnerable.

We’re told about the closing of the company town and the loss of its zip code, and later Fern talks about the death of her husband, and whether she should’ve helped him die sooner, but otherwise we don’t get much background on what they had, what they lost, why she has so little. We just know she’s unsure, alone, living a precarious existence in a van.

She gets a seasonal job at an Amazon Fulfillment Center, boxing up the shit that we all order, then is invited down to a kind of camp in Arizona. It’s run by Bob Wells, who is played by Bob Wells. The movie is based upon Jessica Bruder’s nonfiction book of the same name, and many people play themselves: Bob is Bob, Linda is Linda, Swankie (who has cancer, and an outré personality) is Swankie. They teach Fern the ropes. They teach her how to survive with not much.

It’s an episodic film, as Fern travels from place to place, with the seasons, to get work and survive. We brace ourselves for something bad happening to her—Hollywood has conditioned us for such things—but the bad thing is just the American economy: not the Financial Meltdown version of it but how it generally works. She gets job at Badlands National Park, and at a Wall Drug in South Dakota, and at a sugar-beet processing plant. She’s making it, sure, but if something goes wrong she’s screwed. And something goes wrong. Her van breaks down and it needs repairs she can’t afford. She has to borrow from her sister’s family. She has to take the money on their terms, which is “You have to listen to what we have to say about you.” But it turns out to be almost a bonding moment. It’s “Why did you leave us? I needed you. I would’ve liked having you around.”

She also begins a friendship with another nomad, Dave (David Strathairn, the only other real actor in the film), and the two wind up staying at his son’s place in California. Dave says he has feelings for her. He also says his son is letting him stay there permanently. We see a resolution to her problems. But she doesn’t. It’s not what she wants. So she leaves.

To where? She watches the Pacific Ocean in winter. She gets the Amazon Fulfillment Center gig again. She does a jigsaw puzzle in a laundromat. Then it’s the camp in Arizona again. Her life is cyclical now but with inevitable changes. Swankie is dead, and they all toss rocks onto a fire for her because she loved rocks. Bob tosses one in and says “See you don’t the road.” That’s his philosophy: not goodbye but “see you down the road.” Later, he and Fern talk about the losses in their lives his son, gone five years now, and her husband Bo. Initially it feels like a simple sharing, this non-actor playing himself, and the great, no-bullshit actress doing her great, no-bullshit thing. But she’s in a search for answers and he’s not. His philosophy is so cohesive it’s almost like a religion:

I've met hundreds of people out here and I don't ever say a final goodbye. I always just say, “I’ll see you down the road.” And I do. And whether it's a month, or a year, or sometimes years, I see them again. And I can look down the road and I can be certain in my heart that I'll see my son again. You’ll see Bo again. And you can remember your lives together then.

I like the search better. I like uncertainty better than certainty. Particularly as it relates to down the road.

Enough

But is this the thing that finally helps Fern? He says “You can remember your lives together” because she’d quoted her father, “What’s remembered, lives,” and she adds that maybe she’s spent too much of her life remembering, i.e., not living. She doesn’t have much but she’s still holding on to too much. And in the next scenes, she finally lets go. She returns to Empire, the town that died, and she gives up the stuff she’d been keeping in storage. That’s when I thought of Nietzsche: “He who possesses little is possessed that much less.” (It’s like Marie Kondo without the PR.) Then she tours her old house, with no one there, with no one remotely interested, and heads out onto the road again. And that’s where it ends.

Question: Is that enough?

The movie is certainly atmospheric. It’s both depressing and—well, not exactly uplifting but it has a glint of some possibilities, of life lived in the moment; of a felt life rather than an artificial one. But then there are those Amazon Fulfillment Centers and Wall Drugs to work in, that slow death of the American soul. Is hanging outside the RV at the end of the day, around like-minded folks, enough to counteract that?

“Nomadland” is well-directed by Chloe Zhao, who won an Oscar for it. The movie won best picture. Frances McDormand won her third Oscar.

But is there enough of a story? Enough of an epiphany? Wisdom? Would I ever want to return to it?

Then there’s the fact that the movie was released a year into the pandemic, when we were all still hunkered down, and it was not a good time, and I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to see this movie without thinking of that time. It's not a time I want to return to.

Saturday May 15, 2021

Movie Review: Minari (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Near the end of Lee Isaac Chung’s “Minari,” Jacob and Monica Yi (Steven Yuen of “Burning,” Han Yi-ri), two Koreans trying to make a go of it in the America South of the 1980s, get a bit of good news on a 108-degree day. Actually two good bits of news: 1) they’re told their son David’s heart murmur is healing itself; and 2) Jacob finds a buyer in Oklahoma for the Korean vegetables he’s been growing for most of the movie. Maybe the family won’t have to split up after all.

But on the way back to the car, Monica pulls off and into the shade and Jacob follows. She’s religious, he’s scientific, and she doesn’t like that money somehow is making everything right. “Things might be fine now but I don’t think they will stay that way,” she says. Then she says this:

That was my feeling throughout much of “Minari.” I knew something bad was going to happen and I had trouble bearing it.

Sexing chicks

It’s odd that I felt this way. “Minari” is a gentle, slice-of-life movie about a couple whose immigrant job is determining the gender of baby chickens for the poultry industry—or “sexing chicks.” Jacob is excellent at this, Monica less so, but he has dreams and buys land in Arkansas to grow Korean vegetables to sell to Korean markets for mostly Korean customers. As the opening credits roll, they’re driving there—he’s in a van in front, she’s following in a car with the kids—and, via the rearview mirror, we can see the worry in her eyes grow as they get more and more off the beaten path. Where are we living again? He obviously hasn’t shared his dream with his wife. So right away there’s conflict. And worry over the boy. “Don’t run,” they keep telling him, even when he’s outdoors. Later, they drop the news (to us) about the heart murmur.

I guess I was anxious because stories about people risking it all for their dream usually don’t end well—particularly in indie movies—and farming is particularly fraught. A local diviner tries to sell Jacob his services, but Jacob finds an underground water source on his own. The he hires a local, Paul (Will Patton), to help till the field. Paul is a Korean War vet, talkative, and religious. Extremely so. One Sunday, returning from church, they see him carrying a huge cross along a dirt path, atoning for his (or our) sins. One worries about the harm he might do, but for all his eccentricities he’s a sweet-natured man. One worries about Southern racism, too, but the people are mostly inviting. One boy, a contemporary of David (Alan Kim), asks why he has such a flat face. That’s about it.

Written and directed by Chung, “Minari’ is based on his childhood, so much of the movie is through the eyes of David. Apparently Chung originally wanted to adapt Willa Cather’s “My Antonia,” a lyrical bildungsroman set in the Great Plains in the latter 19th century, but the Cather estate wasn’t interested in adaptations. So he adapted his own life.

Written and directed by Chung, “Minari’ is based on his childhood, so much of the movie is through the eyes of David. Apparently Chung originally wanted to adapt Willa Cather’s “My Antonia,” a lyrical bildungsroman set in the Great Plains in the latter 19th century, but the Cather estate wasn’t interested in adaptations. So he adapted his own life.

As the parents get pulled in the direction of the hatchery (where they earn money) and the farm (which bleeds it), they bring in Monica’s mother, Soon-ja (Youn Yuh-jung), from Korea, to look after the kids. For some reason she’s supposed to share a bedroom with David rather than his sister, Anne (Noel Kate Cho), and David resents it—and her. She’s not your traditional grandmother—watching WWF wrestling, marveling at the bodies of the men, and generally saying the quiet things out loud. When he wets the bed, she says his penis is broken. She drinks his favorite drink, Mountain Dew, and one day swaps his urine for it. She forgives him. She thinks he’s not as fragile as his parents do, telling him how strong he is, and they go for walks together. In the shaded woods next to a creek, she plants a Korean vegetable, minari, which she says grows anywhere—like weeds.

Meanwhile, Jacob’s well literally runs dry, and he goes stiff with exhaustion searching in vain for another. Eventually he has to buy water from the county. Then when the vegetables are ready, his buyer in Dallas backs out, going with a conglomerate in California. Then the grandmother has a stroke. She survives, but her speech is slurred, her body movements jerky.

And all the while I felt: I know this won’t end well and I can’t bear it.

When things fall apart

But it doesn’t end poorly. Jacob finds a potential buyer in Oklahoma, and on that blistering hot day, husband and wife take the kids to make a sale. It works, but Monica is not happy. She’s become more religious, is growing distant from her husband, wants to move mom and the kids back to California. And in the heady afterglow of the sale, she pulls her husband into the shade to have a talk. She not only says the line about things not ending well, she says this:

We can live together when things are good, but when they’re not we fall apart?

To her, that means their relationship isn’t real, but it turns out she has things backwards. Back home, by herself, Soon-ja is trying to help around the house. She even tries to burn some refuse in their burner in the yard, but some items fall out, setting the grass on fire, then the shed where the vegetables are kept, and the family comes home to a conflagration. Jacob and Monica run into the barn, trying to save the vegetables, but the smoke overwhelms them and they wind up merely saving each other. Meanwhile, Grandma wanders down the lane by herself, unable to deal with the disaster she's caused, but the kids run after her and bring her back.

Bit by bit, the family recovers. Jacob tries farming again, this time with the diviner, and David shows him the minari that his mother-in-law planted, which has flourished in the shaded woods. The family stays together. That’s why it’s the opposite of what Monica said. When things were good, she was ready to leave. It took things falling apart to strengthen their bonds.

Is the Yi family the minari? Growing in the new American soil like weeds? Or is the minari a metaphor for some aspect of life? I think of the John Lennon line: Life is what happens when you’re busy making other plans. The well-tended Korean vegetables are the other plans, the ignored minari is life happening. One day you turn around and, wow, look at what's grown.

Thursday February 25, 2021

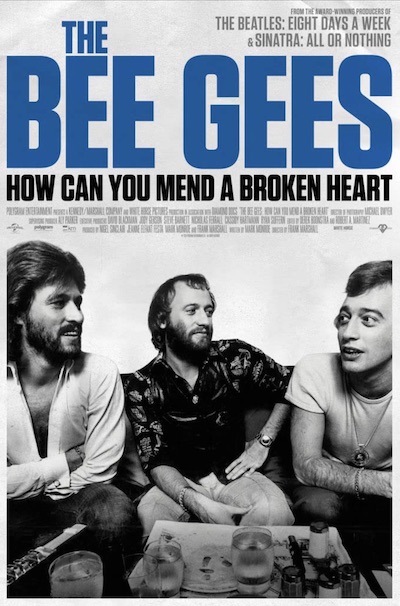

Movie Review: The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Wait, where was “Sgt. Pepper”?

That’s what I asked my wife the day after we watched “The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart” on HBO—a doc we both enjoyed. She gave me a tight smile and laughed a note for what she assumed was a feeble joke.

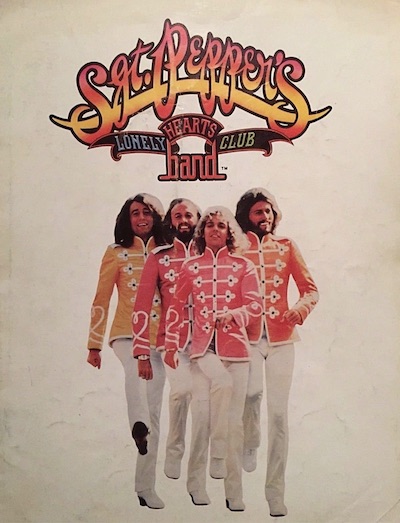

No no, not the album, I said. Or not the Beatles album. The movie.

Blank look.

The movie starring the Bee Gees and Peter Frampton? With the Bee Gees as the Hendersons and Peter Frampton as Billy Shears in an all-star musical of Beatles’ songs? Came out in the summer of ’78. The doc didn’t mention it at all.

The movie starring the Bee Gees and Peter Frampton? With the Bee Gees as the Hendersons and Peter Frampton as Billy Shears in an all-star musical of Beatles’ songs? Came out in the summer of ’78. The doc didn’t mention it at all.

That’s a real thing? she asked incredulously.

A huge bomb. I looked up some of the details. The Bee Gees were filming it in the fall of ’77—right as “How Deep Is Your Love?” was climbing the charts, and months before “Saturday Night Fever” was even released. I’d always assumed they were cast in “Pepper” because of the success of “Fever” but it was before then. It was a Robert Stigwood production, as was “Fever,” and Stigwood was their manager, so I guess that’s why. But it seems worth a mention.

And yes, I get it, you can’t put everything into a 90-minute doc. At the same time, it’s the only feature film the Bee Gees starred in, it was the music of the Beatles, whom they idolized and wanted to be, and it was supposed to be a kind of passing of the torch even if it wasn’t nearly. The release of “Pepper” also adds to the group’s late ’70s oversaturation, which led to the inevitable backlash against them. Which is so much of this story.

Hits

It is fascinating how the Bee Gees and their younger brother Andy Gibb were always being played on the radio, and then how they were never being played on the radio. But to paraphrase “All the President’s Men,” “Don’t tell me you think that all of this was the work of little Stevie Dahl.”

The doc, written by Mark Monroe (“The Cove,” “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week”) and directed by longtime producer Frank Marshall (Bogdanovich, Spielberg), implies as much. We get a great juxtaposition of the Bee Gees playing to sold-out stadiums in the summer of ’79, safe in their bubble, while over in Chicago, Dahl, a tubby, white radio shock jock in army helmet, organized Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park: a White Sox twi-night double-header would cost just 99 cents if you brought a disco record that would get blown up at second base in-between games. It was a fiasco, led to a riot, and the White Sox had to forfeit the second game. A Black usher who was there says he pointed out that a lot of the records being added to the pile weren’t disco at all but R&B—Isaac Hayes and Stevie Wonder albums are shown—adding to the idea that the disco backlash was racist and homophobic in nature. Maybe. Or maybe these stupid white kids grabbed what they could to get into the park. (BTW: Did anyone really destroy “Songs in the Key of Life” for a ChiSox game? Talk about your dumbshit moves.)

There are other cultural touchstones the filmmakers could’ve added besides Dahl. This is a longshot, but I was hoping they’d quote the stream-of consciousness, cultural flotsam thoughts of middle-aged Toyota dealer Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom in “Rabbit Is Rich,” John Updike’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, published in 1981. It's the summer of 1979, Rabbit is driving around in his red metallic Toyota Corona and listening to the radio:

The disco music shifts to the Bee Gees, white men who have done this wonderful thing of making themselves sound like black women. “Stayin’ Alive” comes on with all that amplified throbbleo and a strange nasal whining underneath: the John Travolta theme song. Rabbit still thinks of him as one of the Sweathogs from Mr. Kotter’s class but for a while back there last summer the U.S.A. was one hundred percent his, every twat under 15 wanting to be humped by a former Sweathog in the back seat of a car parked in Brooklyn.

(One can imagine Updike getting canceled today for that second sentence.)

By the end of the novel it’s January 1980, and Rabbit is listening to the radio in a grape-blue Toyota Celica Supra: “Though he moves the dial from left to right and back again,” Updike writes, “he can’t find Donna Summer, she went out with the Seventies.”

When I first read that sentence, decades ago, I found it reductive. But is it? Disco was fucking everywhere in 1979: “Le Freak,” “I Will Survive,” “Knock on Wood” and “Ring My Bell” all topped the charts. Donna Summer had three #1s in 1979 and never another. The Bee Gees had three #1s in 1979 and never another. Maybe we do flip switches that quickly.

And how much of the anti sentiment (of Blacks, disco, gays, sex and Bee Gees) was part of the general rising tide of conservatism that swept the U.K. and U.S. in that period? When the Bee Gees released “Spirits Having Flown” and it went to No. 1 on the album charts in the U.S., U.K., Australia, Germany, Sweden and New Zealand, it was Feb. 1979: gas lines hadn’t begun forming, hostages hadn’t been taken, and Afghanistan hadn’t been invaded. When they released their next album, “Living Eyes,” it was Oct. 1981, Reagan and Thatcher were in power, every dumbfuck around every corner was chanting “USA! USA!” and the album just died. All over the world. In the U.S. and U.K. it peaked at #41 and #73, respectively. Ouch. No wonder Barry Gibb seems so desperate and pissed off when he faces a camera on an early ’80s TV show and says ‘Does anybody mind if we exist in the ’80s? Thank you.” He and his brothers went from everywhere to nowhere. They went out, as Updike wrote, with the Seventies.

And how much of the anti sentiment (of Blacks, disco, gays, sex and Bee Gees) was part of the general rising tide of conservatism that swept the U.K. and U.S. in that period? When the Bee Gees released “Spirits Having Flown” and it went to No. 1 on the album charts in the U.S., U.K., Australia, Germany, Sweden and New Zealand, it was Feb. 1979: gas lines hadn’t begun forming, hostages hadn’t been taken, and Afghanistan hadn’t been invaded. When they released their next album, “Living Eyes,” it was Oct. 1981, Reagan and Thatcher were in power, every dumbfuck around every corner was chanting “USA! USA!” and the album just died. All over the world. In the U.S. and U.K. it peaked at #41 and #73, respectively. Ouch. No wonder Barry Gibb seems so desperate and pissed off when he faces a camera on an early ’80s TV show and says ‘Does anybody mind if we exist in the ’80s? Thank you.” He and his brothers went from everywhere to nowhere. They went out, as Updike wrote, with the Seventies.

No hits

“The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend a Broken Heart” is fun, poignant and brought back a lot of memories. I began listening to the radio with regularity, and American Top 40 religiously, in 1975 when “Jive Talkin’” hit the charts. I never sought them out but I enjoyed a lot of their pre-“Saturday Night Fever” singles: “Nights on Broadway, “Fanny (Be Tender with My Love”) (which I’d completely forgotten), and “Love So Right.” I liked all that; I was a sappy kid. I also liked a lot of the “Fever” stuff, to be honest: “Stayin’ Alive,” “Night Fever,” “You Should Be Dancing.” I just disliked their ubiquity, and the fact that they clogged the top 5 singles charts like no band since the Beatles. That felt like blasphemy to me. Plus I hated “How Deep Is Your Love?” I could never understand why it was so big. Drove me nuts. I remember getting into an argument with my best friend, Peter, at the time. He kept talking up the Bee Gees, I dismissed them, he said who do you like, I said Paul Simon, we mocked each other’s tastes and then didn’t speak for months. Ninth grade.

I do wish Marshall and Monroe had gone a bit deeper and paid greater attention to chronology. Rick Dees’ “Disco Duck” is played as an example of the schlock that followed the Bee Gees’ huge success in 1978, which got people got tired of disco, but it was actually released two years earlier. That matters. Chronology matters.

The broken heart of the title refers to Barry, the band’s leader and only surviving member. Maurice died in 2003, Robin in 2012, while Andy, a huge pop sensation in the 1970s, struggled with drug addiction and died in 1988, age 30. Anyone’s heart would break. “I’d rather have them all back here,” Barry says at the end, “and no hits at all.”

Tuesday January 26, 2021

Movie Review: One Night in Miami (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The first time I heard that Malcolm X, Sam Cooke, Jim Brown and Muhammad Ali got together in Malcolm’s motel room on February 25, 1964, the night Ali/Cassius Clay beat Sonny Liston for the heavyweight championship of the world, I thought, “That should be a play.” Kemp Powers was way ahead of me; it was first performed in 2013. Now he and director Regina King have turned his play into a movie.

And it doesn’t exactly shake up the world.

Immediate takeaways on the four leads:

- Eli Goree is good with the public, loudmouth Clay/Ali schtick, but that’s all he does. He doesn’t give us a private, quiet Ali the way Will Smith did in Michael Mann’s movie. At times I felt like I was watching a cartoon.

- Kingsley Ben-Adir’s Malcolm X suffers the opposite problem. He seems small and slight, without any of Malcolm’s commanding presence.

- I don’t know if Aldis Hodge’s Jim Brown is a good characterization of Brown, since I don’t know Brown, but this guy should be a star. He’s got something. He’s intriguing in the way Tom Hardy was in “Inception.” You wonder what he’s thinking. Handsome as fuck, too.

- OK, if they don’t make the full-length Sam Cookie biopic starring Leslie Odom, Jr., I’m going to be very, very disappointed in Hollywood (for the zillionth time). He’s the right age, a good actor, and his voice is to die for. Get on it.

Cooke v. X

Basics: Behind the scenes, Malcolm prepares to break away from the Nation of Islam even as Clay is preparing to join. But does Malcolm want Clay on his side of this internecine struggle? Of course. Is he willing to ask him? Not according to Peter Goldman in his book “The Death and Life and Malcolm X”:

Basics: Behind the scenes, Malcolm prepares to break away from the Nation of Islam even as Clay is preparing to join. But does Malcolm want Clay on his side of this internecine struggle? Of course. Is he willing to ask him? Not according to Peter Goldman in his book “The Death and Life and Malcolm X”:

The night [Ali] beat Liston, Chicago telephoned him at this victory party—an ice-cream social, more accurately, in Malcolm’s motel suite—and awarded him his membership and his new name; the next morning, reborn Muhammad Ali, he confirmed his conversion to the world. Malcolm liked Ali too well to interfere in this or to involve him further in his private difficulties. When he broke with the Nation two weeks later, he counseled Ali to stay with Mr. Muhammad—and swallowed his hurt feelings when Ali took his advice.

In the movie, Malcolm asks—to not much drama. If you’re going to muck with the history, make it resonate. This doesn’t.

The movie’s main conflict is one we’ve seen many times—radical (Malcolm) vs. moderate (Sam Cooke)—and the movie doesn’t do much new with it. They make both men more extreme versions of themselves to create the conflict, then ease up for the resolution.

Malcolm is about to create a more accommodating version of himself but here he spends the evening haranguing Sam Cooke for being too accommodating. Meanwhile, they all but say Sam is an Uncle Tom. He’s staying at a ritzy hotel in the white part of town, tries to play the Copa before a hostile, white audience, and he’s criticized for singing one way before white crowds and another before Black crowds. “You Send Me” and “Sentimental Reasons” are used as punchlines. His background in the Black church? Unmentioned. His financial and organizational support for Black artists? Unmentioned until the 11th hour. At one point, Malcolm has the effrontery to play Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind”—as if Sam doesn’t know his own industry or art—asking, basically, “How come you don’t do this? This white boy from Minnesota pens something that speaks more to our people than anything you’ve done. How come you don’t get involved in the movement?”

That’s when I knew where they were going. I thought: No no no no. Don’t tell me that because of Malcolm’s pointed attacks throughout the night, Sam will go off and create “A Change is Gonna Come”? Fun fact: By Feb. 25, 1964, Sam had already written, sung and recorded “A Change is Gonna Come”; it was on an LP released that month. But, yes, that’s what happens. We see it a mile off, it’s untrue, but it gives the movie its facile resolution. Oh, and they insult Jackie Wilson along the way, too.

Plus … the movement? Malcolm doesn’t care about the movement. Malcolm attacked the movement. He didn’t hold it up as something to aspire to.

At one point, during the eternal back-and-forth, I thought: “Didn’t Cassius just win the heavyweight championship of the world? Shouldn't this be a little more celebratory? Shouldn’t there be a little more celebrating?” Oddly, Clay becomes a background figure on his big night. Imagine that: Muhammad Ali, a background figure.

Brown v. Board of St. Simons

Of the four, Jim Brown’s internal dilemma is the least interesting: Should he leave the NFL for a Hollywood career? The movie makes it seem like a political decision, a radical act, when both are forms of entertainment for the masses. Jim is either entertaining in a dangerous field where he’s the best by far; or he's doing it in a cushier field where he’s kind of meh. He went meh. But he’s the only one of the four that’s still alive.

That said, the best scene in the movie is Brown’s. It’s when he visits his mother’s former employer, Mr. Carlton (Beau Bridges), in his birthplace on St. Simons Island, Ga. On the porch, he receives a hero’s welcome and lemonade is served. We keep waiting for Mr. Carlton, old, white and Southern, to stick his foot in it but he keeps saying and doing the right thing. Even when his daughter reminds him he has to move a dresser, he doesn’t ask Brown to help as if he’s some servant; he going to do it himself. Amused, Brown offers, but Carlton responds matter-of-factly: “Why, Jim, you know we don’t allow niggers in the house.”

That line is dropped like a fucking hammer. Not only does Brown not expect it, we don’t. We were expecting it, but Carlton had passed our tests and we'd dropped our guard. Excellent writing.

I like that the movie doesn’t give the Nation of Islam a pass. Malcolm and Betty reference Elijah Muhammad’s frequent affairs with his teenage secretaries, while Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee (Michael Imperioli), gets in some digs at the Nation’s absurd origin myth—its theory that all white people are literal devils on this earth. Lance Riddick is powerful, too, as a Nation minister guarding and/or spying on the four men.

Two of the men—the non-athletes—died within a year of this meeting: Sam in December, Malcolm the following February. Both violent deaths. Clay became Ali and a legend, while Jim Brown embarked on a so-so movie career. Ali and Malcolm have risen in stature over the years, Brown and Cooke less so. A good reason to get started on that Sam Cookie biopic.

Saturday January 02, 2021

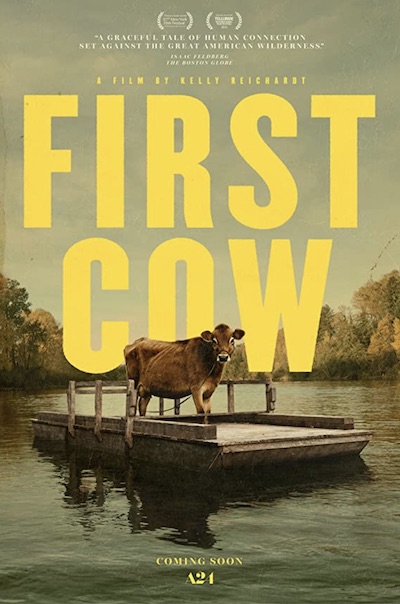

Movie Review: First Cow (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Writer-director Kelly Reichardt’s best-known film is probably “Wendy and Lucy,” about a girl and her dog, and this movie begins with a girl and her dog beside a wide, slow river in Oregon. The dog is sniffing and digging after something until the girl (Alia Shawkat, Maeby from “Arrested Development”) shoos it away; but by then the dog has uncovered a skull. Now it’s the girl’s turn. She digs until she uncovers two skeletons lying side by side, almost in repose, as if they’d died sunbathing. She looks up at the sky with something like wonder.

We don’t have to wonder. The movie will be about those two skeletons: who they were and how they got there. It’s a good framing device.

Not quite kindred spirits

Reichardt has set us up for the story we’re about to see in another way. The first shots in the present are of a boat making its slow way up the wide river, and it’s deliberately, glacially paced—as it is when we begin the story of Cookie (John Magaro) and King-Lu (Orion Lee) in the Oregon Territory in the 1820s. I immediately flashed on Stanley Kubrick giving us the soporific pace of life in 18th-century England in “Barry Lyndon.”

Reichardt has set us up for the story we’re about to see in another way. The first shots in the present are of a boat making its slow way up the wide river, and it’s deliberately, glacially paced—as it is when we begin the story of Cookie (John Magaro) and King-Lu (Orion Lee) in the Oregon Territory in the 1820s. I immediately flashed on Stanley Kubrick giving us the soporific pace of life in 18th-century England in “Barry Lyndon.”

We first meet Cookie collecting chantarelle mushrooms in the damp woods and righting a lizard that has flipped on its back. Then he hears a noise and flees. Sliding down an embankment, he winds up in a fur traders camp. “Frying pan, fire,” I thought. Nope. These are the people he’s traveling with and cooking for. But yes, too. They are brutish men: forever complaining and threatening him.

Cookie is a gentle soul in a brutish world. The next day, or week, or month—who knows?—during one of his forages, he comes across a naked Chinese man, King-Lu, who’s running from Russian fur traders since maybe he killed one of their friends after they definitely killed one of his. And it’s like with the lizard again. Cookie rights him. He brings him a blanket, then offers him his tent, then surreptitiously brings him along on the next leg of the journey.

He hooks up with him again at a trading post. Cookie has done his job, receives his payment, and with part of the money buys himself a new pair of boots. Initially he’s proud. We see him cleaning them, and he wears them, dandyish, with the trouser legs tucked in. Then one Oregon Territory weirdo (Rene Auberjonois, in one of his final roles) comments on them. Then others do. It feels like wolves gathering. The next time Cookie cleans his boots, he leaves the trouser legs untucked to not draw attention.

It’s at a bar that he see King-Lu again. Their conversation is stilted but friendly. King offers him a drink at his shack in the woods, Cookie accepts, he winds up staying. They keep chickens, forage, fish. One flashes back on the epigraph from William Blake that begins the film: “The bird a nest, the spider a web, man friendship.” This is that friendship.

If the first half of the movie is identifying the two men who would become the skeletons along the river, the second half is how they died along the river.

One day, while foraging, Cookie spies the titular cow, which he’d first seen arriving at the trading post, and which is the property of Chief Factor (Toby Jones), a powerful, homesick Brit. That evening, Cookie mentions the cow in passing to King and talks about what he could cook with milk. It’s King who suggests the nighttime raid to steal some of its milk. (Yes, I thought of John Mulaney.) And after a few bites of Cookie’s biscuits, it’s King who goes from impressed to impresario: How much would trappers pay for this? Early on, I thought the two men were kindred spirits, but King is less gentle soul than opportunist, and this is that opportunity. At the trading post, the biscuits are a hit. Long lines form.

I like that Cookie keeps improving the product: now some drizzled honey; now a sprinkle of cinnamon. He’s the artist and artisan. He’s also naturally cautious and assumes the milk raids can’t last. But King, counting the profits, figures the risk is worth the reward.

I was with Cookie. The pace might have been 19th-century but the tension was overwhelming.

Butch and Sundance

The longer they go, the more entwined they become with the man they’re stealing from, Chief Factor, who loves Cookie’s oily cakes, and asks if he can’t make a clafoutis to impress a visiting captain. Shortly thereafter they’re finally caught. Ironically it’s the lookout, King, who gives them away, when the tree branch he’s sitting on cracks and falls under his weight, alerting the household.

Now it’s a chase. In a scene reminiscent of “Butch Cassidy,” King jumps off a cliff and into a river, but Cookie, either unable to swim or unable to find the courage, hides in the bushes. Another irony: He’s the one who winds up wounded when he falls in the woods and hits his head. Eventually the two men reconnect, as we know they must, and attempt to flee to San Francisco. But Cookie is obviously hurt—I almost got nauseous imagining the dizzying head wound—and when they get to the river he has to lie down. King is lookout again, and again fails; soon he’s lying next to Cookie. It’s similar to the way the skeletons were positioned. A man with a gun is pursuing them, but Reichardt, mercifully, leaves them there, in the moment before their final moment. The death we’ve fretted over for two hours is never shown.

“First Cow” was voted the best film of 2020—admittedly a small sample size—by the prestigious New York Film Critics Circle. And while I don’t think it’s that good, it is wholly atmospheric. You feel part of that time. You also feel lucky to be part of this one, where warm homes and baked goods are readily available. The movie is sparse and slow, but those are the very things that make it interesting. The movie is about the lack. I liked it for John Magaro’s kind eyes, and the kind way he talked to the cow. That made the movie for me.

Sunday December 27, 2020

Movie Review: Wonder Woman 1984 (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I guess Warner Bros. and DC Comics don’t need Zack Snyder to make a stupefyingly bad movie.

I’m curious how it all went down. Which Warners exec said, “Hey, we need Chris Pine for the sequel. How do we bring him back from the dead?” And instead of arguing against this inanity, instead of saying that maybe Gal Gadot can carry the fucking movie her fucking self, which hack responded, “Well, what if she just kinda wished him back?”

I don’t even know where to begin with this thing. I guess I’ll begin at the beginning.

1984 redux

We’re in a mall in D.C. in 1984, and some scumbags wearing Don Johnson’s castoffs rob a mall jewelry store, which is, as usual, a front for stolen antiquities. But one of the guys is a blubbery screw-up who drops his gun in the middle of the mall, and some woman screams, “GUN,” and suddenly everyone’s running every which way, including the bad guys.  Then tubby panics again. This time he drops the bag of stolen antiquities in order to pick up a blonde-haired girl and dangle her over the third-floor railing, yelling “I’m not going back! I’m not going back!” Even the other crooks are like, “What are you doing?!” Dude can’t even hold onto her properly. She’s slipping. Which is when Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot, xoxo) swoops in, rescues her, takes care of the bad guys, and knocks out the video cams so there’s no evidence she exists. She’ll just be a rumor that, I don’t know, a hundred people saw that day with their own eyes.

Then tubby panics again. This time he drops the bag of stolen antiquities in order to pick up a blonde-haired girl and dangle her over the third-floor railing, yelling “I’m not going back! I’m not going back!” Even the other crooks are like, “What are you doing?!” Dude can’t even hold onto her properly. She’s slipping. Which is when Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot, xoxo) swoops in, rescues her, takes care of the bad guys, and knocks out the video cams so there’s no evidence she exists. She’ll just be a rumor that, I don’t know, a hundred people saw that day with their own eyes.

Sorry, wait, that’s not the beginning. Before that, we get a prelude on Paradise Island. Diana is a little girl competing in an X Games-like competition with grown Amazonian women, and we get this voiceover from her adult self:

Some days, my childhood feels so very far away. And others, I can almost see it. The magical land of my youth—like a beautiful dream of when the whole world felt like a promise and the lessons that lay ahead yet unseen. Looking back, I wish I’d listened. Wish I’d watched more closely and understood. But sometimes you can't see what you’re learning until you come out the other side.

Me: What’s that lesson? Don’t compete in X Games with grownups when you’re a child?

Nope. Because for most of the race, Diana is winning. (She’s the daughter of Zeus, remember?) She jumps over this, spears that, dives into the other. She’s ahead. But she keeps looking back to see if others are gaining. And one time, bam, right into a branch, which knocks her off her horse and spills her bow and arrow. The horse keeps going, while she sits there, bereft, and is passed by the others.

Me: I guess the lesson is the Satchel Paige one: Don’t look back, something might be gaining.

Nope again. Because little Diana slides down the hill, jumps back onto her horse, and rides it triumphantly into the stadium. She’s moments from wining the race, when her mother, or mentor, I mix them up (Connie Nielsen or Robin Wright), pulls her from her horse, and imparts the movie’s grand lesson: Don’t take shortcuts. Shortcuts are cheating.

As all the world in 1984 is about to find out—and then apparently forget.

Why 1984—that annus horribilis in fiction and fact? According to IMDb, director Patty Jenkins set the film in the 1980s because “it offers the opportunity to explore how Wonder Woman would deal with the types of villains that come from that era.” Meaning con men like Maxwell Lord (Pedro Pascal), who sells the American dream in his cheesy TV ads: “All you need … is to want.” OK, let’s just say it: He’s “Art of the Deal”-era Donald Trump, afraid of being called a loser, who gets rich by selling saps on their wish-fulfillment fantasies. (Cf., Hollywood.)

Wish-fulfillment is also the raison d’etre of one of those stolen antiquities, the “Dreamstone,” which winds up at the Smithsonian and in the hands of Barbara Minerva (Kristen Wiig), a recently hired, well-meaning woman everyone ignores. She’s the opposite of co-worker Diana Prince, who glides through the world tall, athletic, fashionable, gorgeous, desired. At one point, Barbara drops a folder and her papers scatter across the floor; and as she’s trying to collect them, her co-workers walk by her giving disgusted looks. The point is her haplessness, but it does make the staff at the Smithsonian seem like assholes.

Point in their favor? Barbara isn’t even good at her job. She thinks the Dreamstone is a fake, Diana suspects otherwise, and while holding it offhandedly wishes her great love from the Great War, Steve Trevor (Pine), was still alive. There’s a slight breeze, we hear chimes, and that night, at a big gala at which Diana shows up in an insane white dress with slits along the side that make the most of her long, long legs, and who is immediately pursued by every schmuck at the place, at that gala, one of her pursuers, a douchey-looking guy, says the lines that Steve Trevor said to her 60-some years before. And as the camera spins around, he suddenly turns into Steve Trevor. He’s alive again!

OK, let me pause to parse this.

So after the writers—Jenkins, Geoff Johns (DC TV) and Dave Callaham (“Godzilla”)—decided that “wishing” was the way to bring Steve back from the dead, they had to figure out how that would look. Would he claw his way out of his grave? Can’t, right? He blew up in midair. So should he take over the body of someone who recently died? Kind of like a resurrection? I’ll cut to the chase. They decided the best way for Steve to return would be for him to take over the body of someone who’s still alive. In the credits the dude is called “Handsome Man” (Kristoffer Polaha), and while everyone sees him—his face, etc.—Diana and Steve (and us) see Steve. Because it’s Steve who runs the show. His consciousness is what’s in charge. Meaning this other guy has basically been blotted out of existence. That’s what Wonder Woman’s wish did.

And she never wonders about it. Not once. She, a superhero, she snuffs out a life, then she fights the rest of the movie to keep it snuffed. Even when it becomes known that the Dreamstone also takes the wisher’s most prize possession (in WW’s case, her powers) and that you can renounce your wish at any time (which is super nice of the evil deity that set this in motion), she keeps waffling. It’s up to Steve to get her to do the right thing. And even then it’s still tied to that earlier notion that shortcuts are cheating. Of Handsome Man? Nada. Not even a: “Hey, maybe we should give this dude his life back.”

The whole movie is this. Stupidity compounding stupidity compounding stupidity.

Barbara is another unknowing wisher of the Dreamstone. Her wish it be like Diana: breeze, tinkle, poof. At first this means she dresses well, doesn’t stumble in high heels, and men notice her. Then she rips the door off the refrigerator and lifts like 1,000 pounds over her head at the local gym. In the process, she loses her humor and humanity, nearly kills a drunk rapist, and winds up despising Diana for keeping all these goodies to herself. She winds up teaming with Maxwell Lord to make sure wishes aren’t renounced; and because she also wishes to become an “apex predator,” at the 11th hour she turns into the Cheetah, a longtime Wonder Woman nemesis. Meaning, by the end, poor Kristen Wiig is dressed in a cheetah costume, tail and all. Suggestion to Warners/DC: Since Wonder Woman has the worst supervillains ever, either ignore them completely or update them smarter. This was just laughable.

Of the three principles, Max Lord is the one who knowingly wishes on the Dreamstone. His business is about to go under, investors are after him, so he steals the stone—which looks like two broken crystals welded to a rock—and does a version of the clever kid’s “I wish for a thousand more wishes” but dangerously so. He wishes to become the Dreamstone. Me: Wait, wouldn’t his soul get sucked into the rock? That would be my fear. But nope. The essence of the Dreamstone gets sucked into him and the actual Dreamstone disappears amid a cloud of dust. Which on one level might be good. The Dreamstone now has a life expectancy. On the other hand, it can now walk and talk, so it can con people into wishing for the thing it wants, or Max wants, which means more power for it/Max. And with each wish, greater havoc is created, until by the end there’s riots in the streets, the Irish are being rounded up, and both the U.S. and U.S.S.R. have started World War III.

All smiles at Bergen-Belsen

That’s the basics, but I’m still trying to fathom the stupidity. Max travels to Egypt for no real reason (oil, but c’mon; he’s wish king; that’s small potatoes now), and Diana and Steve pursue him (even though at this point they don’t know he’s become the Dreamstone).  And that pursuit in itself is worth a discussion.

And that pursuit in itself is worth a discussion.

How can they get to Egypt?

First, Diana says they can’t fly commercial since Steve doesn’t have a passport. (But doesn’t Handsome Man? And doesn’t everyone see Steve as Handsome Man? Goes unmentioned.)

So she suggests stealing a military jet that Steve will pilot to Egypt. (Wait, she’s assuming a guy who flew Sopwith Camels can fly a 1980s military jet? Also, you’re stealing a military jet!)

But she forgets that radar can track them. (I mean she forgets. Completely. Like a bimbo.)

So she uses some bizarro Amazonian power to turn the plane invisible. (OK. All this for that.)

Even if you want to introduce the invisible plane, it would have taken about two seconds to make Wonder Woman seem like less of an idiot. One: “Don’t worry, Steve, the controls are almost the same as the planes you flew!” Two: “They can track us in the air now—it’s called radar—but I have a way around that!” Instead, she looks dreamily at him and spouts inanities.

The movie screws up even the smallest details. In the first movie, remember, Wonder Woman arrives to help fight the Great War; but in the end she decides fighting doesn’t stop hatred, only love can do that. That’s the needle the filmmakers had to thread because Zack Snyder left them in an untenable position. No one knew her at the start of “Justice League” in 2016 but he’d already placed her with doughboys in WWI. So she kept quiet for a century. And not just any century: one of world wars and cold wars and genocides. What did she do all that time? Did she just sit back and let it all happen?

“1984” gives us a clue. In her D.C. apartment, she keeps several framed photos on her designer tables. They include:

- A newspaper clipping: “THE GREAT WAR ENDS”

- A newspaper clipping: “VFW HONORS LOCAL HERO” (Steve Trevor)

- Steve Trevor next to his plane

- Diana and Etta (Lucy Davis from the first movie) escorting emaciated Holocaust victims out of extermination camps

- An older Etta with Diana in NYC circa early ’60s

First: Who frames small newspaper headlines? They’re not on the wall, they’re on her table. I’ve never seen that. And does she have no visitors? What might one of them say looking over these photos? “So … are you a world war buff or something? Is this flyboy your grandfather? Wow, this woman at the concentration camp looks just like you. But why is that other woman smiling at her? Who smiles at a concentration camp? Shouldn’t both of these women be horrified?”

We certainly should be.

A few years ago, I wrote a blog post on superhero trilogies, and how invariably they follow the same trajectory: powers revealed in I, lost in II, turned evil in III. The 2010s superhero movies got away from that, but here we are again. It’s the second movie, and Wonder Woman’s loses her powers. She doesn’t lose them completely—she can still jump like 80 feet in the air and deflect two out of three bullets—so I guess she winds up with the same power as a normal Amazonian? Maybe the movie explained it and I missed it. Anyway, a shame they’re back on this trajectory. But it’s the least of the movie’s shames.

It’s Henry Cavill’s Superman all over again. The casting is perfect, they’ve got their hero, but Warners is blowing everything else.

Monday December 14, 2020

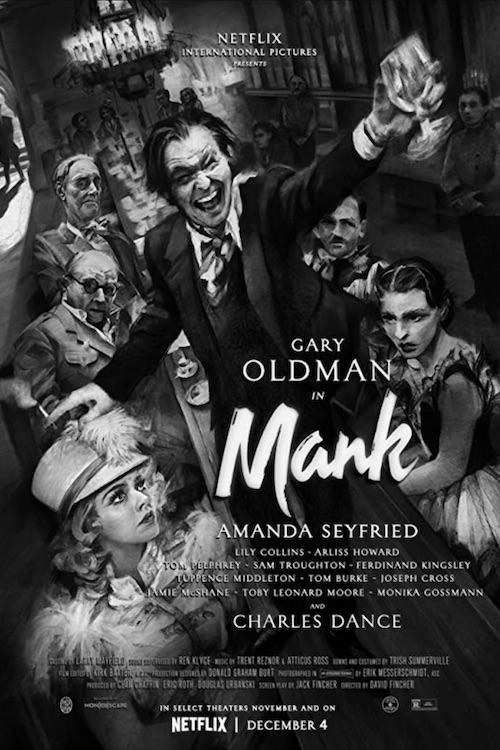

Movie Review: Mank (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

For a movie on such a provocative topic (who is the true author of “Citizen Kane”?), with such a provocative director (David Fincher of “Se7en,” “Fight Club,” et al.), and starring the British version of Nicolas Cage (Gary Oldman, reformed), “Mank” is a bit limp.

It’s not really about who wrote “Citizen Kane” anyway. Early on, it puts its chips on screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz (Oldman) to better explore the why of it. Why would Mank write a movie that disparages his old society friends William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried)? It didn’t have to be them, after all. According to The New Yorker’s Richard Brody, the movie that Mankiewicz called “American” was only one of several projects Orson Welles (Tom Burke), radio’s boy genius, was working on at the time for RKO Studios. Most intriguing among the others? An adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” in which Welles would play both Marlow and Kurtz—but Marlow would never be seen. He would be the camera.

Point of view was also the point of this other film. The initial idea was to explore the life of a powerful person from different perspectives. But which powerful person? Brody writes that Welles and Mank ran through several options—including John Dillinger—before Mankiewicz. suggested Hearst. He was the one who actually knew the man and had been to his castle. “He had suffered and bitten his lip at San Simeon, trying to scrounge drinks,” writes David Thomson in “Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles.” An amusing quote for anyone who’s watched “Mank,” where lip-biting is the last thing Oldman’s Mank does.

Point of view was also the point of this other film. The initial idea was to explore the life of a powerful person from different perspectives. But which powerful person? Brody writes that Welles and Mank ran through several options—including John Dillinger—before Mankiewicz. suggested Hearst. He was the one who actually knew the man and had been to his castle. “He had suffered and bitten his lip at San Simeon, trying to scrounge drinks,” writes David Thomson in “Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles.” An amusing quote for anyone who’s watched “Mank,” where lip-biting is the last thing Oldman’s Mank does.

So if not lip-biting, what reason does the movie offer for Mankiewicz’s desire to tear down Hearst? What is Mank’s “rosebud”—the thing that explains everything?

Why, the 1934 California gubernatorial race, of course.

Citizen Mayer

For more on that election, see Jill Lepore’s excellent 2012 New Yorker article, “The Lie Factory,” about how political consultants Leone Baxter and Clem Whitaker ended Upton Sinclair’s progressive candidacy and ushered in the age of right-wing attack ads. Worth reading and wringing your hands over. Worth making a movie about. But that’s not this movie. In “Mank,” the people we see manipulating the 1934 race for governor of California are not Baxter and Whitaker but MGM’s Louis B. Mayer and his right-hand man—and another boy genius—Irving Thalberg. They attack Sinclair with fake newsreel footage: actors playing hearty, just plain folks who calmly voice support for Republican governor Frank Merriam, while commies and Negroes talk up the radical policies of Sinclair.

All that’s apparently true. They did that. What isn’t true? That Mankiewicz gave a shit.

From Slate’s Matthew Dessem:

I couldn’t find any evidence Mankiewicz supported Sinclair, much less that he carried a grudge for years over the campaign—and it seems likely he would have opposed him on the basis of prose style alone. Still, you can’t pattern a movie after Citizen Kane unless your protagonist has an unhealable wound, so Mank seems to have made this one up.

In other words, the thing that explains everything in “Mank” explains nothing.

But that’s not the problem. It’s a film. Make up what shit you want—just make it resonate. This doesn’t.

The movie makes up more stuff. It pretends that a drunk, cynical Mank gave Thalberg the idea for the fake newsreels in the first place. “You can make the world swear King Kong is 10 stories tall and Mary Pickford a virgin at 40,” he sneers, “but you can’t convince starving voters that a turncoat socialist is a menace to everything Californians hold dear? You’re barely trying.” And the light goes on for Thalberg. It’s good scene.

The other, greater fiction is Mank’s fellow screenwriter Shelly Metcalf (Jamie McShane). Early on, we’re introduced to the writers room at Paramount, and it’s like a Who’s Who of great 1930s screenwriters: Ben Hecht, Charles MacArthur, S.J. Perelman, Charlie Lederer, the Mankiewicz brothers, and Shelly Metcalf. My first reaction was to doubt that all those guys were ever in the same room at the same time. My second reaction was: Shelly Who? Yes. He’s the fictional creation—the guy to make the plot work. He wants to direct, see, and Thalberg finally lets him on the fake newsreels, and he’s so intent on the job he doesn’t realize the immorality of what he’s doing until Mank brings it up; and then he’s so distraught that he kills himself on election night. Shelly’s wife sends Mank to find him, and he does, at the studio, and talks him off the metaphoric ledge. Resigned, Shelly empties the bullets from his gun and hands them over. Mank then goes to the wife and proudly hands her the bullets. “But he had a whole box!” she cries. We can see it coming a mile away. It’s the stuff of melodrama. Not just not true: melodrama.

Here’s the awful thing: They made up all this and it still doesn’t fit. If Mank is angry over the ’34 election, why go after Hearst? Why not make “American” a thinly veiled takedown of Thalberg? Or, since Thalberg was dead by 1940, how about taking potshots at Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard)? Talk about a miserable SOB! Hearst and Davies are at least fun. They admire Algonquin Roundtable wit and Davies shows off some of her own. Mayer is just awful—frowning, knowing none of the talent, understanding zero jokes, and cutting MGM salaries by 50%.

The office

So much of the movie seems just a little off. It opens in 1940 with an injured Mank being helped into bed by a nurse in a hotel in Victorville, Calif., where Orson and RKO have put him up so he can dry out and work on the screenplay. That’s fine. Then we get two flashbacks: the first is just before the crash, when he’s drunk and helped into bed by his wife; the other is the crash. That feels like a flashback—and a bedridden scene—too far. Why not go straight to the jazzy 1930 intro of Charlie Lederer (Joseph Cross), since he’s the through line: the fellow screenwriter who, as Marion Davies’ nephew, introduces Mank to that crowd. And while we’re on him, why repurpose Mank’s great telegram to Ben Hecht (“You must come out at once. There’s millions to be made and your only competition is idiots.”) as if he sent it to everyone, including Lederer, who, as a Hollywood resident, certainly didn’t need it?

Why fictionalize the secretary’s husband into an RAF pilot? So Mank can misread the room while she’s reading the MIA letter? It’s just another scene we see coming a mile away. Why pretend John Houseman (Sam Troughton) didn’t stick around and nurse the script? And why have him tell Mank: “Write hard. Aim low.” The whole point of “Kane” is that Welles had carte blanche at RKO. They could write as high as they wanted—and did. More, “Aim low” feels like the last thing John Houseman would ever say. Right, Mr.…Hart?

At least, we hear some great lines. After LB gets MGM staffers to cut their salaries by 50%—and to applaud their own disenfranchisement—Mank gives a drunken shrug: “Not even the most disgraceful thing I’ve ever seen.” I also like LB’s line on the way to the fleecing:

“This is a business where the buyer gets nothing for his money but a memory. What he bought still belongs to the man who sold it. That’s the real magic of the movies, and don’t let anybody tell you different.”

Or how about Thalberg’s line to Mank about how at least he believes what he’s doing. “But you, sir. How formidable people like you might be if they actually gave at the office.” Another line, similar in spirit, is Mank’s about his Hollywood career:

“I came for a few months. I don’t know how it is that you start working at something you don’t like, and before you know it, you’re an old man.”

That’s from Brody’s article but it should’ve been in the film. That’s the heart of it. Mank knew he’d wasted his life, “Kane” was redemption, but he’d agreed to keep his name off it; so he sued to get it back on. Because it was the moment he gave at the office. And he knew the office would never let him give that much again.

Tuesday July 28, 2020

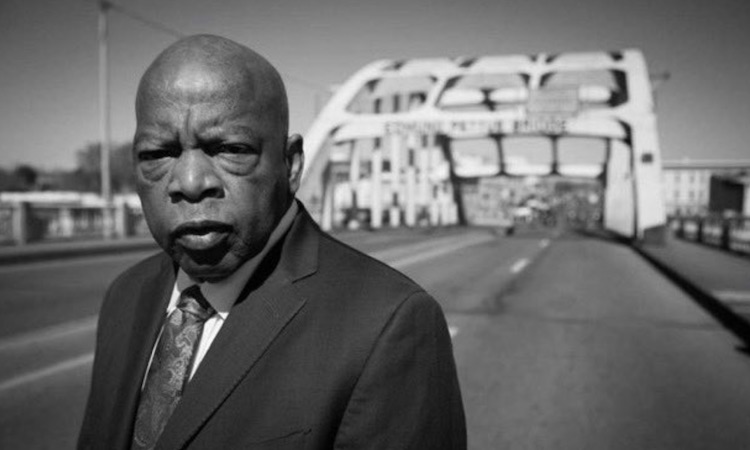

Movie Review: John Lewis: Good Trouble (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Dawn Porter’s documentary, “John Lewis: Good Trouble,” is a celebration of the life of the civil rights icon and a warning that his life’s work is being undermined in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder ruling. It chronicles his rise from an obscure farm in Troy, Alabama and onto the world stage, gives us his greatest hits from 1960 to 1965—Nashville sit-ins, Freedom Rides, March on Washington, Selma—and follows him around during the 2018 midterms as he campaigns for Democratic candidates in Texas and Georgia. Post-credits, we also get a Covid-era Q&A conducted over Zoom between Lewis and Oprah, which is like a master class in interviewing. Seriously, if you’re interested in journalism, watch it and learn it. She keeps going back, keeps politely digging, trying to find something new and deeply felt beyond the stories that have long been memorized and memorialized.

She even asks the very question that I wanted to ask Lewis, but lacked the courage to do so, when I saw him on a book tour in 2000: “After facing all of the dangers you’ve faced, what can possibly still frighten you? What are you still afraid of?”

She even asks the very question that I wanted to ask Lewis, but lacked the courage to do so, when I saw him on a book tour in 2000: “After facing all of the dangers you’ve faced, what can possibly still frighten you? What are you still afraid of?”

It turns out: Nothing. Here’s the exchange:

Oprah: You talk about losing your fear at that moment on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. I want to know if you lost it forever and from that day forward you became a fearless warrior for civil rights? Or have there been times when the fear was there and you just used your bravery and courage to move forward? Did you lose your fear completely or were there days where you still felt it?

Lewis: I lost my fear.

Oprah: Completely?

Lewis: Forever.

Oprah: Wow.

Lewis: On that bridge, I thought I was going to die.

Oprah: Can you pause right there? I’ve heard you say that before. What does that feel like? When you think you’re going to die?

Lewis: Well, Oprah, I had what you call an executive session with myself. I said, “This is it. I’m going to die on this bridge.” And I thought others was going to die. And somehow, in some way, maybe history intervened or God almighty kept me. And I’m glad he kept me.

Oprah: But in that moment, when you’re thinking you’re going to die, are you also thinking, “But this was worth it”?

Lewis: Oh, I thought, along the way, if I have to do more than shed some blood, and I must die, this is worth dying for.

Oprah: Mm.

Lewis: [Here gets emotional.] My own mother, my own father, my uncles and aunts, my teachers, could not register to vote. So I had to do something. I had to bear witness to what I felt was the truth.

I’ve interviewed tons of people in my career and I’ve long known that you can ask the best question in the world and get bupkis, and then some offhand comment will bring up the most fascinating vein of material. I don’t know if Oprah’s small, sympathetic “Mm” elicited that emotion from Lewis, or if it was the follow-ups she was asking, or if he was going there anyway. But he got there. I think with her help.

The boy from Troy

My wife and I watched the doc the weekend after Lewis died from pancreatic cancer. It had been released a few weeks earlier, and in better times he might have been at its premiere, thin and hobbled, but these aren’t better times. So the doc was simply released online without much fanfare; and there it was the weekend after he died.

It could’ve been tighter. I think we get too much in 2018—maybe a little too much back-and-forth with his chief of staff, Michael Collins, as they josh about Michael not knowing that Texas grew cotton, or about all the kisses Lewis received from the ladies at the local church. Sometimes the joshing veers into uncomfortable territory, as if the two are a long-married couple getting on each other’s nerves. I guess that’s kind of fascinating but it still made me uncomfortable.

I like the scene of Lewis voting in the 2018 election at his local polling place: looking around, admiring the turnout. Made me think of all the other times he voted in midterms when there were no cameras following him and the turnout wasn’t so good. Did he ever wonder, “I got my skull fractured for this?” But that wouldn’t be him. And anyway 2018 was different, 49.3% turnout, the highest for a midterm since 1914. In that campaign, we see him stumping for Colin Allred, who wound up defeating Pete Sessions 52-46, and Lizzie Fletcher, who turned Texas’ 7th district blue for the first time since 1967. The House turned blue. The Congressional black caucus wound up with a record 55 members.

We also seem him campaigning for Stacey Abrams for Georgia governor, and Beto O’Rourke for the U.S. Senate. On election night we hear him say, “I’m so sorry about Stacey and this kid.” This kid. Love that. We get about 10-15 seconds of Beto here, and it’s so electrifying it makes you wonder what might’ve been. If he’d won the Texas seat, would he be the Democratic candidate for president now? Maybe. But he lost, narrowly, and every week or so Ted Cruz’s stupid head pops up on my Twitter feed to provoke or prevaricate while the world crumbles.

The Abrams loss was worse because it points to voter suppression—the very thing Lewis spent his life fighting. The doc gives us some of the sad post-Shelby County numbers:

- 27 states adopted voter ID laws

- millions purged from voter rolls

- more than a thousand polling stations closed

I know the weak GOP arguments for the first two, but is there any argument for closing polling stations? Making people stand in line for hours and hours to participate in a constitutional right? How does that help democracy?

Interspersed with all this is black-and-white footage from the march toward those voting rights the GOP is now curtailing. A lot of the footage I’ve never seen before. A lot of the footage John Lewis had never seen before. That’s what he says to the camera: “Dawn, I’ve seen footage I’ve never seen before.” Maybe I saw some of it back on the “Eyes on the Prize” days? Did they show Rev. James Lawson’s non-violent workshops in that doc? Or Lewis and his roommate Bernard Lafayette talking by a creek about how they were involved in the protests despite the concerns and fears of their parents? Or Lewis speaking at the March on Washington, and extolling the crowd, “Wake up, America, wake up!” while Bayard Rustin, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, hangs behind him?

Lewis didn’t have Martin Luther King’s voice—who did?—nor his words. What did he have? He was a slight kid with a childhood stutter and a thick Alabama accent who had the quiet courage of his convictions. That was it; that was his superpower. He was literally willing to die for the cause. He was also handsome. I always thought so anyway. A bit of nerd, too, standing there on the Edmund Pettus Bridge with his backpack on over his tan overcoat. The other day I saw photos of Lewis at a Comicon a few years ago, after the graphic novel, “The March” came out, and cosplaying as his younger, iconic self: tan overcoat, backpack. Beautiful.

What happened after SNCC sloughed him off for rabble-rouser Stokely Carmichael in 1966? We don’t get that story much. We do here. He went to Mississippi with Julian Bond to register people to vote. He was gaining weight and losing his hair by then. He worked in the Carter administration—although doing what we never find out—then became a city councilman in Atlanta. And in 1986 he ran for the U.S. House from Georgia’s 5th District. Against Julian Bond. I had no idea. I know a lot about Lewis but I had no idea about this. (I guess I don’t know a lot about Lewis.) And though Bond was tall and handsome, and better known, Lewis won in an upset. He brought up a Reagan-era issue, drug testing, and was willing to take one, and Bond wasn’t, and maybe that tipped the scales. It probably did with their friendship. Bond never ran for public office again, while Lewis kept representing the 5th every day until July 17, 2020.

Everybody’s hero

Lewis has long been my hero—I’ve written about that to the point of boredom—so it was great finding out that he was everyone’s hero—or at least that part of the public that cares an iota about our history. We get shots of him walking through an airport in 2018 and everyone stopping him to shake hands, get pictures taken. We hear stories about being in a Ghanaian marketplace and shouts being heard: “John Lewis!” Or from an Egyptian cabdriver. The director asks … one of his brothers? ... or Congressional staff? I'm not sure. I apologize. But she asks what’s it like walking through an airport with Lewis. After a pause, he deadpans, “Tedious.”

Some of the celebration of Lewis here, his indispensability, comes across as ominous in the wake of his death. Listen to these quotes knowing he’s gone:

- Hillary Clinton: His voice and his example are probably needed now as much as they’ve ever been.

- Nancy Pelosi: He challenges the conscience of the Congress every day he is here.

- Stacey Abrams: You cannot replace a John Lewis.

One of his last acts in the House was introducing and urging passage of the new voting rights act, HR1, “For the People Act,” whose purpose is to “expand Americans' access to the ballot box, reduce the influence of big money in politics, and strengthen ethics rules for public servants.” The House passed it and sent it to the U.S. Senate in March 2019. It hasn’t left Mitch McConnell’s desk. A newscaster in the doc tells us “Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell says the Senate will not vote on HR1,” and he’s been true to his word. It's as if racists don’t need armed state troopers anymore. They have Mitch McConnell.

The title comes from Lewis’ main stump speech: “My philosophy is very simple: When you see something that is not fair, not right, not just, say something, do something! Get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble!” “Good Trouble” is like that. It's a good doc, a necessary doc. We should all watch it. Listen to his words and translate them to our era. What’s going on in this country post-Shelby County? Let’s say something and do something. At the least, let's do what John Lewis’ own mother and father, and his aunts and uncles, were prevented from doing most of their lives: vote.

Monday July 13, 2020

Movie Review: Palm Springs (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Could infinite time loops be their own genre? The form would be more constrained than most, of course, but maybe that would spur imaginations. It could be the villanelle of movie genres, with Harold Ramis as its Dylan Thomas.

They certainly feel appropriate to the Covid era. Who doesn't feel trapped these days? Who doesn't wake up and think: Oh right. This again. Fuuuck.

Nov. 9

Unlike “Groundhog Day,” which begins with the first day Bill Murray gets stuck in the time loop, “Palm Springs” gives us Nyles (Andy Samberg) already stuck in it for who knows how long.

We don’t know that initially. We see him and his girlfriend, the vapid Misty (Meredith Hagner, fantastic), staying at a motel on the day of the wedding of their friends, Tala and Abe (Camila Mendes, Veronica of “Riverdale” and Tyler Hoechlin, Superman of the DC TV universe). He has sad morning sex with Misty, swims and drinks beer in the motel pool, shows up (in Hawaiian shirt and swimsuit) late to the wedding reception, where he rescues the bride’s sister, Sarah (Cristin Milioti), from having to give a speech by giving his own: a semi-profound talk about how we’re all born lost, and love and marriage is when we’re found. He’s glib, like an “Animal House” fratboy, but surprisingly meaningful, like an old soul. Like someone who’s lived countless lifetimes.

We don’t know that initially. We see him and his girlfriend, the vapid Misty (Meredith Hagner, fantastic), staying at a motel on the day of the wedding of their friends, Tala and Abe (Camila Mendes, Veronica of “Riverdale” and Tyler Hoechlin, Superman of the DC TV universe). He has sad morning sex with Misty, swims and drinks beer in the motel pool, shows up (in Hawaiian shirt and swimsuit) late to the wedding reception, where he rescues the bride’s sister, Sarah (Cristin Milioti), from having to give a speech by giving his own: a semi-profound talk about how we’re all born lost, and love and marriage is when we’re found. He’s glib, like an “Animal House” fratboy, but surprisingly meaningful, like an old soul. Like someone who’s lived countless lifetimes.

Saving Sarah from fumbling her speech is part of a plot to sleep with Sarah. It almost works. At first she’s like “What about your girlfriend, dude?” and we cut to the two of them crouched outside a motel room where another wedding guest is going down on Misty. Then it’s Nyles and Sarah in the desert, making out; then out of nowhere Nyles is shot by an arrow from a paramilitary dude named Roy (J.K. Simmons). Chased, Nyles crawls into a cave that pulses red like a beating heart. Sarah follows him in to see if he's OK. He yells at her to leave. She doesn’t.

Fffttt!

Then it’s the next day. Or the same day. “Palm Springs” doesn’t begin with his first time-loop day but hers. The cave—which opens up during an afternoon earthquake—is where it happens.

It’s an interesting wrinkle to the formula: What happens when you have someone to share that same day with? Who won’t re-set like the rest of the world? How much better does it make it?

Not necessarily better. Turns out Roy is another wedding guest with whom Nyles once got high in the desert; and when Roy said he’d love to live out there forever, a stoned Nyles introduced him to the cave. He wasn’t happy. Every so often, he chases down and tortures Nyles.

Sarah isn't happy, either. She wants out, and immediately latches on to the “Groundhog Day” lesson: It’s karma, and to break free they need to be better people, and she needs to do a selfless act. Doesn’t work. She tries to kill herself. Ditto. Eventually she calms down and the two act like high school kids playing hooky. They goof around, waste time, prank the other guests. They go to a shooting range, steal a plane and crash it, go to a dive bar and synchronize dance. They begin to enjoy themselves. They wake up with smiles on their faces. Every day doesn’t matter but they have each other.

But then the reveals. He admits that during his solo infinite loop, they had sex maybe a thousand times. She reveals—or he finds out—that the bed she wakes up in every morning is not hers but the groom’s, her sister's betrothed, and she’s wracked with guilt. Eventually, she simply disappears every morning, leaving Nyles bereft. But she's going to the local diner to study quantum physics. To get the fuck out of Dodge. Thankfully, she's a quick study. She realizes that if they blow themselves up in the cave at the exact right moment…

I’ll cut to the chase: It works.

Nov. 10

The movie was made for Hulu by writer Andy Siara (“Lodge 49,” shorts) and director Max Barbakow (shorts), and it's not bad. I laughed throughout. I think I laughed the hardest at that chaotic scene when the beautiful Tala falls on her face and breaks her two front teeth before the wedding. Sandberg’s got the Know-It-All’s smirk down; Milioti is smarter but not as funny. Hagner as Misty is a stand-out. Simmons is becoming our weathered wise man: Sam Elliott with anger issues.

Time-loop movies always make me wonder what I’d do in that situation. I think, initially, I'd assume I was in purgatory and paying for my moral failings. But since every day was without consequences, there would be that urge to have more moral failings. I might also do all the stuff I don’t have time to do now: become fluent in Chinese and French; research the books I want to write. Maybe I’d finally read “Ulysses” or “Remembrance" or the Bible. Would I travel? Get half- or quarter-days in Paris or Shanghai or Kauai? Eventually, I assume, I would go mad. Or does that just mean you wake up sane again?

Here, since you could bring others into the time loop with you, I was wondering if they would inundate the cave with guests—flood the zone, as it were—and hope they broke free. Or: rather than study quantum physics—good luck with that—how about bringing a quantum physicist through the cave with you? So you’d have him on your side. What would the world be like if you had a thousand or a million people restarting on the same day but retaining their memories? When would it begin to feel like you were eternal? When would it feel less like hell and more like heaven?

For all the laughs, the ending of “Palm Springs” disappointed me. He was in the loop for, what, 10 years? Twenty? So what would you do the glorious day you finally broke free? Guess what they do? The same shit they were doing in the loop: lounging in a nearby pool and drinking beer. Huge disappointment.

It does lead to a joke about the family that owns the pool. He says: “I guess they return on November 10.” Meaning the time-loop day was November 9. Which also happens to be the day after Donald Trump was elected president. What a fucking day to be stuck in. Here’s to breaking free of all that.

Sunday July 12, 2020

Movie Review: The Assistant (2020)

WARNING: SPOILERS

There’s a moment in “The Assistant” when I lost a little respect for our title character.

Jane (Julia Garner of “Ozark”) is a quiet, nervous assistant—one of three, and the only female—to a powerful unseen boss (voice: Jay O. Sanders) in a New York-based film production company. Halfway through the film, after a helluva day, she goes to see the head of HR, Wilcock (Matthew Macfadyen), in the gloom of his small, dim office. Most of the offices in the company are small and dim. Assuming you even have an office. Everyone there feels broken. They suck up to the people above them and bully those below, but no one seems to want to leave. They want to stay close to power even as it breaks them. It’s a company of quiet desperation.

We assume we know why Jane is at HR. Her unseen boss seems like a Harvey Weinstein type and we figure she’s going to lower the boom. The movie has been called a #MeToo movie but it’s really a #PreMe movie. It’s about everything that’s suspected but isn’t said. But we figure our girl has the goods.

She doesn’t. She blows it.

Bernstein redux

This is how she begins:

This is how she begins:

“Uh, there’s this girl who arrived here today. She’s from Boise. And she’s very pretty. And she’s young.” Wilcock, taking notes, seems confused, and Jane continues. “She was waitressing in Sun Valley when she met him. And he liked her, apparently, and just gave her an assistant job.”

That’s Jane’s first salvo and we immediately know it won’t land. There’s no accusation there, just vague innuendo.

What’s her second salvo? Reiteration of the first salvo. Boise girl, no experience, he flew her in and put her up in a hotel. “She’s very young,” Jane adds, as if that seals the deal.

It doesn’t. Wilcock doesn’t even know—or pretends not to know—what’s she’s implying. He asks, “Has this girl done something to harm the company?”

Some part of the movie loosened for me there. I lost interest. I was thinking maybe Jane wasn’t a character worth following around.

Couldn’t she have said something like this? “OK, this is a film production company, and so I get that there are young, good-looking girls hanging around all the time, but I keep coming across a weird vibe with it all. I have to stock the Boss’ desk with drugs and hypodermic needles? And I find used hypodermics in the carpet? I find other things in the carpet, too. A hair tie. An earring. The girl who owned the earring came by today and she seemed despondent, broken, and I don’t know why. Maybe the interview didn’t go well? Or is it worse? I don’t know. But the vibe is not good.”

Own up to the ambiguity. Again, I was hoping she would shed light. For us. Doesn’t she look at the drugs she stocks in his desk? Is he a diabetic? It’s possible. We could be condemning a man who simply has a problem with his pancreas.

You know what the back-and-forth between her and the HR rep reminded me of? Woodward and Bernstein in “All the President’s Men.” Bernstein was forever assuming the evidence meant X, Y and Z, and Woodward was forever reining him in and sticking to the facts. Ditto Harry Rosenfeld: “I’m not interested in what you think is obvious,” he says to Bernstein early on, “I’m interested in what you know.”

Check out this dialogue from “The Assistant”:

She: What can we do?

He: Do about what?

She: About the girl.

He: OK, let’s … bear with me here. … So a new assistant arrives, from out of town, and she’s being put up at The Mark. And your boss at some point left the office.

She: To meet her at The Mark, yes.

He: Yes, according, apparently, to the jokes at the office.

She: Yeah, I guess.

He: So … that’s it? That’s why you came in?

Here’s the thing: Are we supposed to sympathize with her here? Because she annoyed me. She kept fumbling. At the same time, her most egregious error, her great missed opening, is still coming up.

L’espirit de l’escalier