Monday December 10, 2012

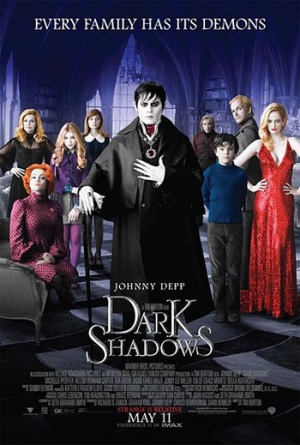

Movie Review: Dark Shadows (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“This thing is spectacularly off,” I said.

“I keep waiting for it to find a rhythm,” Ward responded, “and it never does.”

We were halfway into Tim Burton’s “Dark Shadows,” surely one of the worst movies of the year. The cast was good, the trailer looked funny, the reviews were OK. In The New York Times, Manohla Dargis called it enjoyable; on Salon, Andrew O’Hehir trumpeted Michelle Pfeiffer’s return to the screen (after only a year away?), while on Slate, Dana Stevens wrote, “[Burton] and Depp, both avowed childhood fans of the original series, seem to be in their element and having a grand old time.” Turns out these positive reviews were in the minority. Among top critics on Rotten Tomatoes, “Dark Shadows” garnered a 37% rating, which, to me, is still 37 percentage points too high. It’s an abysmal movie.

Sleepy, Hollow

It opens with 10 minutes of backstory. In the 18th century, the Collins family, including young Barnabus, leave Liverpool, England, for the wilds of Maine, where they start a fishing empire, create the town of Collinsport, and build the stately, gothic mansion known as Collinwood.

It opens with 10 minutes of backstory. In the 18th century, the Collins family, including young Barnabus, leave Liverpool, England, for the wilds of Maine, where they start a fishing empire, create the town of Collinsport, and build the stately, gothic mansion known as Collinwood.

Barnabus, of age now, and played by Johnny Depp, is about to diddle the servant, Angelique (Eva Green), who asks if he loves her. He cannot tell a lie: he doesn’t. Hell hath no fury like a woman—or, in this case, witch—scorned, and she uses her powers to kill his parents by falling steeple. Distraught, he descends into the black arts, but manages, through the pain, to find his one true love: Josette (Bella Heathcote, this decade’s Heather Graham). Ever jealous, Angelique compels Josette to throw herself off Widow’s Hill, turns Barnabus into a vampire, then turns the town against him. A torch-wielding mob descends, chain him in a coffin, and bury him alive for 200 years. Cue credits.

It’s now 1972. A young woman on a train, who looks like Josette (same actress), is obviously hiding something (she changes her name, per a Victoria, B.C. travel poster, to Victoria Winters), and heading for a job as a governess at Collinwood, now decrepit. There, she and we meet the modern, dysfunctional Collins family: matriarch Elizabeth (Pfeiffer), who is starched and overly proper; her eye-rolling teenage daughter, Carolyn (Chloe Grace Mortez); Elizabeth’s brother, Roger (Jonny Lee Miller), a weak, shallow man who ignores the needs of his son, David (Gulliver McGrath), whose mother died at sea three years earlier. David claims he still sees his mother; he claims he still has conversations with her. That’s why Collinwood has an in-house shrink, Dr. Julia Hoffman (Helena Bonham Carter, of course), who arrives at evening meals frequently plastered. There’s also a disgruntled butler/handyman, Willie (Jackie Earle Haley), who is frequently plastered, and whose every joke falls flat.

Barnabus Returns

Only after meeting all of them, as well as the ghost of Josette who plagues Victoria, do we get the resurrection of Barnabus by a night-time construction crew, each of whom screams, runs and crawls from this nightmare. Barnabus then goes to Collinwood and we meet the family all over again: Elizabeth, Carolyn, Roger, et al. Elizabeth wants to keep Barnabus’ secret—that he’s a 200-year-old vampire—from everyone, including the family, so she introduces him as Barnabus III. From England. All of these jokes fall flat. Then Barnabus meets the new governess, Victoria, who looks exactly like his long-lost true love, Josette, and discovers that his nemesis, Angelique, has survived all of these years and is now running the town.

What does he do? Get revenge on Angelique? Court Victoria, who looks like his one true love?

Neither. He sets about restoring the family name and reputation. We get a montage—backed by the Carpenters’ “Top of the World”—of workers sprucing up Collinwood and the Collins Canning Factory opening its doors again. When Barnabus finally meets Angelique, she makes a pass at him; the second time they have rough sex. He also sucks the blood out of a band of hippies in the woods. Then he kills Dr. Hoffman, who, under the pretense of curing him of vampirism, and wanting eternal youth, tries to turn herself into a vampire. Before this, she goes down on him. Later, Barnabus throws a ball headlined by Alice Cooper. “Balls are how the ruling class remain the ruling class,” he says.

His revenge? Forgotten. His one true love? Whatever. What should be driving the story forward isn’t, and what is driving the story forward isn’t funny.

Occasionally we get bits where Barnabus grapples, to humorous effect, with 1972 mores. He sees the golden-arched “M” of McDonald’s as a sign of Mephistopheles. He wonders over the sorcery of television and yells at Karen Carpenter, singing on a variety show of the day, “Reveal yourself, tiny songstress!” In Dr. Hoffman’s office, he shakes his head and says, “This is a very silly play.” Cut to: an episode of “Scooby Doo.”

But most of the movie is scattered, pointless, painfully tin-eared.

Beetlejuiceless

All of it leads to a final confrontation between the Collins family and Angelique, where we find out, in a pointless third act reveal, that long ago Angelique turned Carolyn into a werewolf. We also find out that it was Angelique who killed David’s mother at sea. At this point David’s mother finally reveals herself, in all her howling fury, and destroys Angelique.

Why didn’t David’s mother do this sooner? Why didn’t Barnabus? Why do the Collinses consider Barnabus worthy of the portrait over the fireplace when it was Barnabus’ father who built up everything? And since when do witches turn men into vampires?

The fault isn’t Depp’s: his line readings; his reaction shots, are generally good. But nothing anyone else does is worth a damn. Tim Burton lets his freak flag fly. He paints Johnny Depp chalky white again, as in “Edward Scissorhands,” “Ed Wood,” “Willie Wonka,” and “Sweeney Todd.” He has the living and the dead raise a family again, as in “Beetlejuice.” But there’s no juice here. Burton’s always been a lousy storyteller, sacrificing plot and plausibility for imagery, but even the imagery here feels stale. Burton’s love of the dead finally feels dead.

My favorite moment? The end. And not because it’s the end but because of the Hollywood hubris it represents. As Barnabus and Victoria, both vampires now, kiss on the rocks beneath Widow’s Hill, the camera dives underwater and heads out to sea, where we come across the body of Dr. Hoffman in cement shoes. And her eyes suddenly open. Ping! The end. It’s a set-up for a sequel that will never be made. It’s an ending that assumed a success that never came.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)