Movie Reviews - 1970s posts

Tuesday March 19, 2024

Movie Review: High Plains Drifter (1973)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Just as “Pale Rider” was “Shane” with an avenging angel, this is “High Noon” with an avenging angel. You have a town of cowards, newly released prisoners coming toward them, and a lone man with a gun. Right, it’s not exact. In order to be more exact, Marshal Will Kane, rather than imprisoning Frank Miller, would’ve been killed by Miller and his brothers, the town would’ve been complicit in the killing, and as “High Noon” began, Gary Cooper would’ve ridden into town to enact revenge: to humiliate every man and rape every woman, before killing his killers and then riding off into the sunset.

It's a little sick, to be honest.

In Clint Eastwood’s previous film, “Joe Kidd,” he outmans everyone. This is that on steroids. Every man is weak and sweaty but him. Every woman resists him until he kisses them. Nobody can shoot anything and he can shoot everything.

Oh, he also stands up for Indians and little people—as he stood up for Mexicans in “Kidd.” Who knew Clint Eastwood was our original virtue signaler?

Rape and a haircut

I think I first saw “High Plains Drifter” in the late 1970s, edited for television, but probably not edited enough. Even then it was a little unappetizing for me. Maybe I empathize too much with cowards or people who can’t shoot straight.

I think I first saw “High Plains Drifter” in the late 1970s, edited for television, but probably not edited enough. Even then it was a little unappetizing for me. Maybe I empathize too much with cowards or people who can’t shoot straight.

I’d forgotten the town was next to a picturesque lake. I’d obviously forgotten the name of the town, Lago, which is Spanish for lake. It hardly looks like a mining town—more like a future tourist destination, as it is: Mono Lake in the California Sierras. The shooting location was actually scouted by Eastwood himself. Then he had the town built there. The man in charge of construction/design was Henry Bumstead, who also built the town of Sinola for “Joe Kidd” and Big Whiskey for “Unforgiven.” He was an art director for 30 years, 1949-1979, then kept going with production design—though most of his work in the ’90s and ’00s was strictly for Eastwood. Which speaks well of Eastwood.

This is Clint's first western as director, and there’s an eerie, shimmering quality to it, augmented by an ethereal score, but also a blunt, sweaty palpability. The Stranger rides into town, past a graveyard that includes the names of Clint's past directors—Sergio Leone, Don Siegel—which is either homage or declaration of independence. Or both.

Everyone watches him and no one says a thing. Finally he goes into the saloon, orders a beer and a bottle, says he wants a peaceful hour in which to drink it. He doesn’t get it. Three yahoos interrupt him. Turns out they’re the men the town hired for protection against the three main baddies, Stacey Bridges (Geoffrey Lewis in his first Eastwood) and the Carlin brothers (Anthony James and Dan Vadis), who are about to be released from prison. But they’re yahoos, and for some reason—the same reason young subway juvies pick on Charles Bronson—they decide to pick on the tall, quiet stranger. He deflects and walks away—to the barber, a sweaty, shaking, man with a greasy combover (William O’Connell), for a shave and a bath. This is an iconic scene. Mid-shave, the yahoos appear. They taunt and threaten and attack. And the stranger shoots them all with the gun he’s holding beneath the barber sheet. (Hey, a little Han Solo from “Star Wars,” isn’t it?)

After that, we get the first rape. Callie Travers (Marianna Hill) bumps into him on purpose, chastises him, insults his manhood; so he takes her to a barn. Later, in his room, as he closes his eyes, he sees a man being whipped to death and begging the townspeople for help. This, it turns out, is Marshal Jim Duncan, played by veteran stuntman Buddy Van Horn, and the stranger is either his brother, his ghost or his avenging angel. The town is more than cowardly; it’s corrupt. Its mine is on government land, meaning none of the riches are theirs. Marshal Duncan planned on going public with it, so (I think) the town hired Bridges and the Carlins to kill him, then turned them over to the authorities. That’s why they’re worried about their return.

And that’s why they look to hire the stranger. He’s uninterested … until they say he can have anything he wants. “Anything?” he asks. So he keeps upping the ante. These boots, these blankets and candy for the Indians, a round of drinks on him. He makes the town dwarf, Mordicai (Billy Curtis), the sheriff. When the mayor laughs, he makes him mayor, too. He keeps requisitioning material: your barn, your bedsheets, your wife. He does try to train them—putting snipers on this and that roof—but they’re hopeless shots. Mostly he humiliates them. It gets bad enough that several band together to try to kill him. Instead, lighting a stick of dynamite with his cigar (a la Leone), he blows up most of the hotel.

Oh, and he has them paint the town red (literally), then renames it (unsubtly) “Hell.” And just before the baddies arrive, he leaves, going the other way.

And now it’s the baddies’ turn with the town.

That night, the stranger returns. Against a hellish backdrop of burning buildings, he whips one to death, hangs another with a whip, and takes down Bridges in a gunfight. As he leaves the next morning, exiting the way he entered, he passes Mordecai making a grave marker for the fallen Marshal. “I never did know your name,” Mordicai says, to which the stranger replies, “Yes, you do.” Then the camera pans to and holds on the tombstone.

So yeah, not the brother.

True spirit

According to Richard Schickel in “Clint Eastwood: A Biography,” the initial script IDed the Stranger as a sibling, and Clint started out playing it that way. But “I thought about playing it a little bit like he was sort of an avenging angel, too.” All of which adds to the ambiguity.

“High Plains Drifter” did well at the box office, while critics were mixed—though its Rotten Tomatoes score is 94%, with one of the rotten reviews ironically coming from Schickel. But it did gangbusters with teens of my generation. That, I remember.

Who didn’t like it? John Wayne. Again, from Schickel:

Clint recalls Wayne saying to him more than once, “We ought to work together, kid.” So when he found a script in which he thought they might costar Clint sent it on to Wayne, noting in his cover letter that the piece, though promising, needed more work. Too much more, in Wayne’s estimation. But in rejecting the proposal, he launched into a gratuitous critique of High Plains Drifter. Its townspeople, he said, did not represent the true spirit of the American pioneer, the spirit that had made America great.

Schickel sees this as “an argument between modernism and traditionalism, but I think it’s something more specific. “High Plains” riffs off of “High Noon,” which Wayne hated, because it’s a metaphor for the blacklist. Which he was in favor of. I think Wayne was still fighting that fight.

The movie is well-directed, cleverly directed, and the story is tight. It's just the other stuff I have a problem with. But apparently we will never tire of a seething moral righteousness given license to act immoral. We love that story so much we carry it into the world.

Saturday March 16, 2024

Movie Review: Joe Kidd (1972)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The town name is a joke, right? From screenwriter Elmore Leonard? Sinola? Apparently there’s a Sinaloa, Mexico, but this is New Mexico, circa 1902, and I’m not seeing anything. Or maybe I just don’t know shit from Sinola.

This is the movie Clint Eastwood made after “Dirty Harry” and it’s not bad, despite its 6.4 IMDb rating. Maybe it’s so low because Eastwood himself didn’t much like it, or didn’t like making it with director John Sturges, who was often drunk on set. Sturges, for his part, didn’t much like trying to direct Eastwood, either.

Do we even know what the title character does? We know he used to be a tracker and bounty hunter, and we see how he’s dressed, in tweed suit and derby, a more citified look than we’re used to from western Eastwood, but I don’t think we ever find out his current occupation. Cattle rancher, maybe?

Eastwood v. Nosotros

Joe Kidd begins the movie sharing a jail cell with two Mexican yahoos after getting drunk and losing a fight with Sheriff Mitchell (Greg Walcott). He begins down. He then proceeds to outman everybody. Whatever a man is, Joe Kidd is more:

Joe Kidd begins the movie sharing a jail cell with two Mexican yahoos after getting drunk and losing a fight with Sheriff Mitchell (Greg Walcott). He begins down. He then proceeds to outman everybody. Whatever a man is, Joe Kidd is more:

- He protects the townsfolk more than the sheriff

- He protects the Mexican people more than the Mexican revolutionary

- He’s more ruthless than the ruthless landowner

It’s the second one that made me shake my head. “Naw, don’t go there, Clint. Naw … Aw, fuck.”

He’s in the courtroom, sentenced to 10 days for the contretemps with Mitchell, when Mexican rebels, led by Luis Chama (John Saxon), burst in. They’re tired of losing their land to the Anglos; they’re tired of white men going back on their word. So Chama decides to kidnap the judge (John Carter) to make things right. Why the judge? Who knows? But in the confusion, Kidd rescues the judge, then, behind the bar of a saloon, sipping a beer and holding a shotgun, he waits for the Mexican rebels—in particular Naco (Pepe Callahan), with whom he’d had an escalating tete-a-tete in jail. Naco wouldn’t let the hungover Kidd have coffee, Kidd pours slop stew on him, Naco tries to clock him but Kidd knocks him out with the pan. He figures Naco wants revenge. He does. He doesn’t get it. Blam.

In the calm afterwards, the wealthiest man in New Mexico, Frank Harlan (Robert Duvall), shows up with an entourage of sureshots and jerks, and they attempt to hire Kidd to help them track and Kill Chama—whom Duvall keeps calling “Chay-ma.” Kidd begs off. He’s got nothing against Chama. But then he finds out Chama, as payback for Naco, invaded his ranch home, rustled his horses, and hurt his right-hand man. So off he goes with them.

Damn, if Naco had only let Joe have that cup of coffee.

Kidd regrets his decision quickly. The men reveal who they are, killing some Mexicans in cold blood, then, with leers, kidnapping Helen Sanchez (Stella Garcia), who, unbeknownst, is Chama’s girl. They take a small Mexican village hostage and shout out to Chama—hiding in the nearby mountains—that they’ll kill five hostages in the morning unless he surrenders himself. Then five at noon, then five at … .You get the idea. Harlan choose this moment, stupidly, to betray Kidd, who’s disarmed and put in with the hostages. But of course he finds some arms, kills some men, including the loudmouth Lamarr (Don Stroud), and brings the girl to Chama in the mountains.

Which is where she finds out Chama had no intention of sacrificing himself for the people below. Becoming martyrs in his name, he says, would be a good way to die.

The original script wasn’t like that. Per IMDb:

John Saxon said “Clint needed to be the guy who dealt with all the action, so in the end Chama was smeared with self-serving and cowardice, so it was clear who the main hero was.” Saxon attended a NOSOTROS meeting, a Latin American organization opposed to stereotypes, and publicly apologized for playing such a dubious character.

Then it just gets dumb. Chama doesn’t want to sacrifice himself but somehow Kidd convinces him to turn himself in? Kidd shouts down the deal to Harlan and everyone heads back to Sinola, but Harlan and his men stop a train to get there first. Oh right, one of the men, the sharpshooter Mingo (James Wainwright) stays behind to kill Chama and crew before they reach Sinola, but he’s killed instead. By Kidd. Who out sharpshoots the sharpshooter.

Jesus, Clint, leave something for somebody.

Judge, jury, executioner

In town, Kidd sends the rest of Chama’s men away (why?), then rides a train into the saloon and starts killing the bad guys. Then he tracks Harlan to the courthouse, and, from the judge’s chair, kills him in cold blood. After Chama turns himself in, Joe decks the sheriff. He tells him, “Next time, I’ll knock your damn head off.” Don’t really get his anger at the sheriff—who suddenly turns into a goober at this point. I guess it’s payback for the stuff we didn’t see at the beginning? It's outmanning everybody.

Beautiful scenery, though. And apparently the weaponry is very accurate for the time it’s set. Duvall is his usual impeccable, awful, oddball self. The gang is great, particularly Wainwright as Mingo, the sharpshooter, who’s both cool and casually cruel. I like Lynne Marta as Elma, Harlan’s concubine, who is kissed by Kidd in the early going and doesn’t mind at all. She’s cute. Died this year, sadly.

This was the phase of Eastwood’s career when he was popular with the crowd but called a fascist by the critics—before he became a critic and Academy darling whose movies did so-so box office. Before his movies became shitty and no one went to see them.

I get his appeal. It’s just problematic. In his next one, “High Plains Drifter,” it’ll be worse.

Monday February 05, 2024

Movie Review: The Long Goodbye (1973)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I recall watching Robert Altman’s “The Long Goodbye,” based on the 1953 Raymond Chandler novel, about 20 years ago, and coming away confused and dissatisfied. Now I get why. The movie is confusing. It’s untraditional. It mixes Chandler’s penchant for complicated plots and hidden motives with Altman’s love of overlapping dialogue and improv, with an early ’70s So Cal loopiness. Add that up and, well, confusing.

This time, though, I liked it.

I mean, who knew Jim Bouton was the Orson Welles of the 1970s?

Go home, Martins

It’s totally an Altman film. It’s Altman doing genre and fucking with the conventions.

It’s totally an Altman film. It’s Altman doing genre and fucking with the conventions.

Take the yoga-loving, half-naked female neighbors. All the men who come through, the cops and the hoods, stare, gawking, while our man Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) barely notices. He walks by muttering under his breath about his cat. He couldn’t be less interested. Is that why the girls are interested in him? Why they call out to him? It’s the opposite of most detective fiction. There’s beautiful women everywhere and he beds nobody. In the uptight 1940s, with the Production Code staring down furiously, Bogart couldn’t enter a bookstore or take a cab without coming away with a little. But Gould in the free-love 1970s? With naked women everywhere? Not a drop. He doesn’t even seem thirsty.

But he smokes like a chimney. They kept that in. There seems no shot where Marlowe doesn’t have a cigarette going.

The opening is fun, but a little lame if you know cats. The late-night convenience store doesn’t have his cat’s favorite food so he gets another kind, puts it in the tin of the favorite kind, then dishes it out like it’s that one. Why in God’s name does he think this will work? Cats don’t care about tins. Cats care about smell. And it’s the wrong smell. And there goes the cat.

And in comes Marlowe’s friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton). We’d seen him leaving his gated community, scratches on his face, bruises on his knuckles, and now he’s asking Marlow to drive him to Tijuana. Marlowe does. When he returns, cops are waiting. Seems Lennox’s wife, Sylvia, is dead, Terry is the prime suspect, and Marlowe just helped him get away. Accessory after the fact.

When he gets out out of the slammer, certain of Terry’s innocence, he’s got a gig waiting. Eileen Wade (Nina van Pallandt, a super-tanned Dane) is worried about the disappearance of her husband, an alcoholic, Hemingway-esque writer named Roger Wade (Sterling Hayden). Marlowe finds him in a detox center run by the creepy Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson) and springs him. Then they drink and argue, and Hayden chews the scenery. Apparently a lot of this was improv. It shows.

What does any of this have to do with Terry Lennox? Turns out the Wades knew the Lennoxes: neighbors and friends. Oh, then mob boss Marty Augustine (actor-director Mark Rydell) and his men descend on Marlowe because Terry owes them $350,000 and they figure Marlowe has it or can get it. There’s a lot of Altmanesque craziness here. Augustine busts his girl’s face with a Coke bottle to show he means business; later, to come clean, he has himself and his men, including a non-verbal Arnold Schwarzenegger, strip to their skivvies. Meanwhile, at a party at the Wades, Dr. Verringer shows up demanding money from Roger, and that night Roger walks into the ocean. Do we see him again? Does he die? Either way, Eileen confesses to Marlowe that Roger was having an affair with Sylvia Lennox. So maybe Roger killed Sylvia and that’s why he was acting so erratic? And Verringer knew?

At some point, Marlowe finds out Terry’s dead—he killed himself in Mexico. But then Marlowe gets a $5,000 bill in the mail from Terry, along with a goodbye letter; and then the $350k is magically delivered, freeing Marlowe from Augustine. I assume all that gives him pause. Because down in Mexico, using the $5k as a bribe, Marlowe discovers Terry isn’t dead. He faked the suicide. More, he was schtupping Eileen Wade. More more, he killed his wife. He’s the guy. Marlowe comes upon him laying in a hammock, and Terry admits it. He’s blasé about it. He didn’t mean to, he says, but he did it.

So Marlowe kills him in cold blood.

Here’s the thing: Before Marlowe arrives to confront him, we see Marlowe walking on a dirt road under a canopy of trees, and I said to my wife, “Looks like ‘The Third Man.’” And then we get the confession and the killing of the killer. Which, yes, is exactly like “The Third Man.” Throughout that movie, Holly Martins is looking for Harry Lime’s killer, and, alley oop, it turns out to be him. Same here, mostly. Throughout, Marlowe is looking to prove Terry innocent; instead he proves him guilty, then acts as judge, jury, executioner.

Altman underlines the parallel again. We return to the canopy of trees, Marlowe is walking away and Eileen is driving in. She stops but Marlowe keeps walking toward the camera. It’s “Third Man” with genders reversed. I’d call it homage if it didn’t seem like such a rip off.

Anyway, that’s why Jim Bouton is the Orson Welles of the 1970s.

The canopy of trees, and the long walk, after killing the friend whose murder you were trying to solve.

The meaning of yoga

That ending doesn’t quite work, does it? First, it’s too “Third Man” but not nearly good enough. Second, it’s the only time when Marlowe seems awake. He’s focused and in control, but his actions are over-the-top. In cold blood? Really? It’s out of character. It's completely unlike the sleepy, mumbling dude we’ve spent two hours with.

So was the ending imposed upon Altman by the studio? Nope. It was in the original Leigh Brackett script, and Altman liked it so much, or wanted to do the “Third Man” homage so much, he put in a contract clause that the ending couldn’t be changed without his approval.

It’s not, however, the Raymond Chandler ending. In the novel, yes, Terry killed Sylvia and faked his suicide, but he and Marlowe don’t meet in Mexico:

Then on a certain Friday morning I found a stranger waiting for me in my office. He was a well-dressed Mexican or Suramericano of some sort. He sat by the open window smoking a brown cigarette that smelled strong. He was tall and very slender and very elegant, with a neat dark mustache and dark hair, rather longer than we wear it, and a fawn-colored suit of some loosely woven material. He wore those green sunglasses.

It's Terry, with plastic surgery, in his new identity as Señor Maioranos. At some point in the conversation Marlowe figures it out, they wrangle out the rest in the shrugging, elliptical Chandler manner, and say their goodbyes. I guess that’s where the title comes from. “So long, amigo,” Marlowe tells him. “I won’t say goodbye. I said it to you when it meant something.”

Chandler's ending makes more sense—for the title, for Marlowe, for everything.

But the movie is still fun. Apparently Bouton was a last-minute replacement for Stacy Keach (Bouton compared it to asking some fan to go play third base for the Yankees). Hayden was also a replacement—for “Bonanza”’s Dan Blocker, who died before filming began. There’s only two songs in the entire movie: “Hooray for Hollywood,” which opens and closes it; and “The Long Goodbye” by John Williams and Johnny Mercer, of which we get about five renditions—including one by Jack Riley, Elliott Carlin of “The Bob Newhart Show,” who has a cameo playing piano at a bar. That made me smile.

So did the moment when the half-naked female neighbor explains what yoga is. Someone should make a reference book about when current everyday items/concepts had to be explained in movies. Yoga in this, the CIA in “Charade.” Others?

Tuesday January 16, 2024

Movie Review: Escape From Alcatraz (1979)

WARNING: SPOILERS

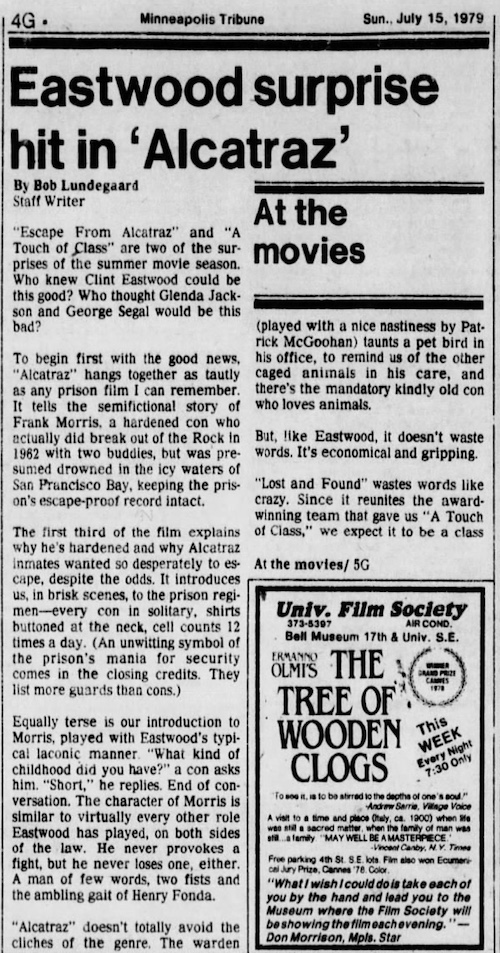

In the 1970s, my father was the movie critic for The Minneapolis Star-Tribune, my friend Dan R. was a big Clint Eastwood fan, and rarely the twain met. Eastwood may have been big at the box office but generally not with critics. I believe Pauline Kael even used the f-word for him: fascist.

One day, though, I was happy to report to Dan that my father actually liked Clint’s latest. Dan was unimpressed. “Probably means I won’t,” he said flatly.

I don’t know if Dan ever saw “Escape From Alcatraz,” but it’s not exactly a departure for Eastwood. He plays another strong, silent type dealing with men who want to break him down (Warden Dollison, played by Patrick McGoohan), fuck him up (guards, mostly) or just fuck him (Wolf, played by Bruce M. Fischer). But he survives. He wins. Every battle.

If the movie is a departure it’s because it’s based on a true story—a rarity for Clint in those days. It’s also a procedural, which is probably why my father liked it. It’s methodical and factual. It’s all about the how of a prison break.

The Shawshank distinction

Was “Alcatraz” the first movie I saw where prison rape was implied? I think so. It came out a year after “Scared Straight!” didn’t shy away from the topic.

Was “Alcatraz” the first movie I saw where prison rape was implied? I think so. It came out a year after “Scared Straight!” didn’t shy away from the topic.

Clint plays Frank Morris, who was sent to Alcatraz in 1960, and escaped with two others, John and Clarence Anglin (Fred Ward and Jack Thibeau) in 1962. Whether they truly escaped, or drown in the attempt, as the FBI contend, is still unresolved, but the movie leans toward escape. On Angel Island, 2+ miles from Alcatraz, and only a half mile from the mainland, Warden Dollison finds a chrysanthemum on a rock. Chrysanthemums, he’s told, don’t grow on Angel Island, but they were the symbol of hope and freedom for an inmate, Doc (Roberts Blossom), whose life the warden ruined. The flower, it’s implied, is a private message from Frank. A final fuck you.

Bigger point: Did Stephen King see this? He must have. He was a big movie guy and this was a popular movie, the 14th highest-grossing film of 1979. Three years later he published “Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption” and there are parallels:

- Prisoner protagonists with high IQs

- Working out of the prison library

- Being the target of rape/attempted rape

- A battle of wits with the warden

- The slow chiseling of weakened concrete

- Releasing excavated concrete/dirt in the prison yard via pants legs

- “Nobody ever escaped from Alcatraz/Shawshank”

“Shawshank,” the movie, makes the parallels more explicit. In the novella, Andy Dufresne is short; in the movie, he’s a tall drink of water like Clint. In the novella, Red is white. In the movie, he’s black, like English (Paul Benjamin), Frank’s kinda-sorta best friend in stir in “Alcatraz.” In the novella, Andy doesn’t hide his chiseling tool in a Bible—the way Frank does with the warden’s nail file and the way the movie Andy does with the rock hammer.

Both movies give us the feel-good camaraderie of a group of prisoners. Frank’s group includes:

- Doc, whose painting privileges are rescinded when he paints an unflattering portrait of the warden. He winds up cutting off his fingers in protest.

- Charley Butts (Larry Hankin), a new, dopey prisoner, and Frank’s neighbor, who is in on the prison break but chickens out at the last minute.

- Litmus (Frank Ronzio), who keeps a pet mouse in his shirt.

- English, the black con, who heads the prison library, and who taunts Frank (and is taunted back) with “boy” comments.

That said—and calm down already “Shawshank” fans—they’re completely different movies. “Alcatraz,” as mentioned, is a procedural. The prison break is step-by-step, which means we’re in on it throughout, which means we’re anxious throughout. Will Frank get caught? Can they make it to the water? Can they make it across the water? In “Shawshank,” Andy’s prison break comes as a surprise. We assumed he was leaning toward suicide.

Indeed, the difference in films is the exact distinction Alfred Hitchcock between suspense and surprise. Hitchcock sets up a scene: a ticking bomb beneath a table where two men are talking. Now you could direct it, he says, so the bomb just goes off. Or you could show the audience the men talking, then the ticking bomb, then the men talking.

In the first case, we have given the public 15 seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second we have provided them with 15 minutes of suspense. The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed—except when the surprise is a twist: that is, when the unexpected ending is, in itself, the highlight of the story.

Which it is in “Shawshank.”

Boy toys

Something else I pondered watching “Alcatraz” in 2024: Was Clint a little racist or did he just keep pandering to his base? Or did he like ruffling liberal feathers?

All of the above?

I’m thinking of “I gots to know,” and that scene in “Jersey Boys”: “Come back when you’re black,” which is one of the most insulting lines in movie history.

Here, Frank not only calls English “boy,” but say to his face, “I guess I don’t like niggers,” and it’s fine. It’s fun. Because English started it both times. English keeps calling Frank “boy” until Frank, amused, responds in kind; and when Frank visits him in the bleachers in the black section of the yard, where he sits on the top step, a king of the hill, and then Frank, maybe out of respect, doesn’t sit with him, English says it’s either because he’s scared or because “You don’t like niggers.” At which point, Frank plops himself down next to him and says the line.

I’m probably overreacting. But the scenes do have a ’70s vibe rather than a 1960 vibe. The dynamic feels post-Black Power, rather than, you know, lunch-counter sit-in.

But the dynamic, and the rapport between the actors, is good, and they become friends. And in the end, Frank lets him know, subtly, that he’s breaking out, and offers his hand through the bars. After that, the day of the escape, Wolf is gunning for Frank in the yard with a shiv but English stops him. He puts him in a headlock and guides him to the black area of the yard. Because in the end black people watch over us? Because Frank represents hope, which is a good thing, and no good thing ever dies?

Anyway, my memory is correct: Dad liked it. Dan has yet to weigh in.

“A man of few words, two fists and the ambling gait of Henry Fonda” pretty much sums up the Eastwood persona.

Friday February 11, 2022

Movie Review: Soylent Green (1973)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“It’s people! Soylent Green is made of people!”

Yes. Also sheets. Chuck failed to mention that. Dead bodies go down a conveyer belt draped in white sheets, get dumped into a vat of goo, and the next thing they’re the titular green slabs on another conveyer belt. So I might worry more about the sheets. At least people are organic.

“Soylent Green” came out when I was 10 but I was never drawn to it. The original poster made it seem like garbage trucks were after Charlton Heston, which isn’t exactly thrilling; and once I knew the last-act reveal, which everybody knew soon enough, why bother?

Why bother now? Because the movie is set in 2022. Yes, the future is here and it’s dystopic.

Admittedly they get a few things wrong.

The end of Rico

For one, they imagine out-of-control population growth, with New York City stuffed to the rafters with 40 million people. Our hero, Detective Thorn (Heston), is forever stepping over the kerchiefed, slightly Sovietish masses sleeping in stairwells. Yet NYC’s current population (8.4 million) isn’t far off from what it was during filming (7.6 million). High rents help.

Outdoor scenes were shot through a greenish filter, to emphasize the out-of-control pollution, but we’re better off than that. Women's rights? Again wrong. In their world, feminism didn't take. Women are furniture. That’s literally what they’re called—at least the young pretty ones who come with an apartment, such as Shirl (Leigh Taylor-Young, hot), who becomes the Love Interest. She’s Furniture to William R. Simonson (Joseph Cotton), a member of the vaguely governmental body called “the Exchange” that runs things, but he’s killed in the first act. Thorn is the detective working the case. He’s the hero but as corrupt as anyone. Or he’s corrupt in the way those in dire straits are corrupt. He steals to survive—to get a little something-something for him and his partner, a police analyst, or “Book,” named Sol Roth (Edward G. Robinson), with whom he lives in a cramped apartment.

Aside: It was fun watching Robinson, who was blacklisted 20 years earlier just for being liberal, and future NRA president and GOP darling Charlton Heston acting together and seeming to enjoy each other’s company. This is Robinson’s final movie role: He died of cancer in January 1973—post-production but pre-release. He also dies, via assisted suicide, in the film—a fact that some critics had trouble with back in ’73. They shouldn’t have made him act a death scene when he was dying! Me, I’m just happy Eddie, nee Emanuel Goldenberg, got to play Jewish for once. L’chaim, kid.

What else? No masks in this 2022 world because no global pandemic. But the one portent of the future the movie got right is a good one:

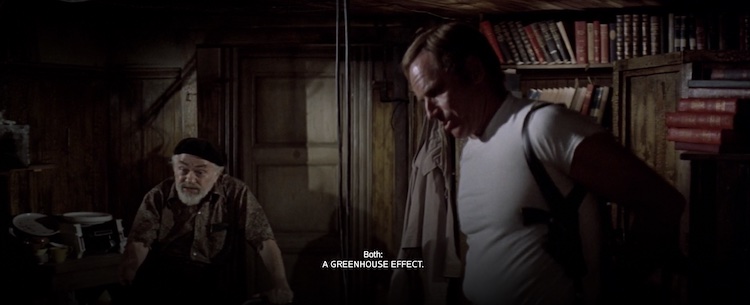

Sol: How can anything survive in a climate like this?

Sol: A heat wave all year long.

Both: A greenhouse effect.

Apparently it’s the first time climate change was used as a plot device in a film. Thank god we listened to the warning.

“Soylent Green” isn't bad but it fails to cohere in places. Thorn is forever moaning about the state of the world without knowing what it used to be. And he's not really good at his job. Mostly he’s interested in cadging a strawberry here, smoking a cig there, schtupping Shirl everywhere. Sure, he figures out some stuff. Simonson’s death wasn’t the result of a break-in—more like an assassination—and the orders probably came from the Soylent Corp. He figures the bodyguard (Chuck Connors) was in on it, too. But it’s Sol who realizes why Simonson was offed. Simonson found out something, couldn’t live with it and was ready to talk.

Sol can't live with it, either. That’s another odd moment. Thorn gives Sol two volumes of “The Soylent Oceanographic Survey Report” from 2006 and 2015, Sol discovers their secrets (the ocean’s dying, plankton are dying, Soylent Green is people), and, with no reveal to us, he takes his findings to “the Supreme Exchange”—old people in the stacks of a library. The Exchange Leader (Celia Lovsky, one-time wife of Peter Lorre, who played T’Pau on “Star Trek”) tells him they need proof before they can present it to the Congress of Nations. So Sol goes out and gets that proof.

Kidding. He agrees to be euthanized without telling Thorn what he's learned.

That's an odd turn, right? “Hey, I have earth-shattering news! Oh, you need proof? I'm outta here.” Plus, aren't the book volumes proof enough? Or is the Exchange asking for proof knowing he won't be able to get it, Sol senses this and that's why he opts for death. Either way, Thorn arrives before Sol dies and Sol whispers the secret to him (with no reveal to us) and tells him to get proof. Yet another odd turn: Thorn thinks he gets it! He hops a ride to a plant, sees it all for himself, and at the end, wounded in a crowded church after a final fight with Chuck Connors, he tells his captain, Hatcher (Brock Peters), “You don’t understand. I got proof. They need proof. I’ve seen it. I’ve seen it happening.”

Yeah, that's not proof. “I’ve seen it” isn’t proof. And this guy is a detective? Maybe they should’ve sent a journalist.

Anyway that sets up our famous strident outcry at the end:

Listen to me, Hatcher. You've gotta tell them! Soylent Green is people! We’ve gotta stop them! Somehow!

At which point there's a freeze frame and the camera zooms in on Thorn’s bloody hand as it points to the sky. And that’s the end. You gotta love ’70s cinema.

So much is left unanswered. Will Thorn live? Is Soylent going to kill him? Is Hatcher in on it? He stuck him on riot control duty so Simonson's assassin could have a shot at him, yet in the final shots he seems empathetic. So was he just following orders? But whose? I assume the Soylent Corp., but where are they? Who are they? We never see them. They should've shown us. Soylent Corp. is people, after all. It's people, I tell you!

You blew it up, etc.

Strident outcries in the final shot, condemning man’s inhumanity to man, were Heston's bit back then. Cf., “Planet of the Apes.” Dystopias, too. Prior to this he starred in “Omega Man,” based on the novel “I Am Legend,” in which, for much of the film, Heston thinks he’s the last man on Earth. In that one no one’s around, in this one everyone’s around. Some say fire, some say ice.

From here, Heston starred in disaster flicks (“Earthquake,” “Airport 1975”), period pieces (“Three/Four Musketeers,” “Crossed Swords”) and the final refuge of stars of his era, the western (“The Last Hard Men,” “The Mountain Men”). By the early '80s he was done as a leading man, but he'd had quite a run. Adjusted for inflation, two of his films (“The Ten Commandments” and “Ben-Hur”) are among the 15 biggest box-office hits in U.S. history. Yet it's the striden outcries that keep on ringing. When AFI counted down the top 100 movie quotes in Hollywood history, only two Heston lines made the cut: “Take your stinkin' paws off me, you damn dirty ape!” at 66; and “Soylent Green is people!” at 77.

Tuesday October 05, 2021

Movie Review: Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)

WARNING: SPOILERS

You can’t get much more ’70s than this.

It’s a road movie about two mismatched grifters, filmed on location in the small towns of Montana, with dusty car chases, a drive-in movie, nudity and misogyny, and a plaintive Paul Williams song on the soundtrack. The heist goes wrong and no one wins. The ending is downbeat as the era required.

This was Michael Cimino’s directing debut. His second film, “The Deer Hunter,” would win five Oscars, including best picture and director. His third was “Heaven’s Gate,” and there went his career—along with movie studios’ love/tolerance of auteur directors. That probably would’ve gone away anyway, when movies like “Jaws” and “Star Wars” showed the path, but “Heaven’s Gate” didn’t help. Cimino got to do this one because Clint Eastwood liked his screenwriting for “Magnum Force,” the second Dirty Harry movie, released a year earlier, and basically said “Have a go at it, kid.” Apparently Eastwood wanted to do a road movie.

The inspiration for the film is about as far afield from a ’70s road movie as you can get: a 1955 Douglas Sirk romance/comedy, “Captain Lightfoot,” starring Rock Hudson as the titular Lightfoot and Jeff Morrow as Captain Thunderbolt, a pair of Irish scallywags who have various adventures in 1815. But if you dig a little, there’s a connection of sorts. “Captain Lightfoot” was written by, and based upon a novel by, W.R. Burnett, who basically created the modern gangster tale (“Little Caesar”), and the modern heist tale (“The Asphalt Jungle”), and whose screenwriting credits include 1932’s “The Beast of the City,” starring Walter Huston as a police chief who takes the law into his own hands. That movie is often cited as a forerunner to, yes, “Dirty Harry.”

The inspiration for the film is about as far afield from a ’70s road movie as you can get: a 1955 Douglas Sirk romance/comedy, “Captain Lightfoot,” starring Rock Hudson as the titular Lightfoot and Jeff Morrow as Captain Thunderbolt, a pair of Irish scallywags who have various adventures in 1815. But if you dig a little, there’s a connection of sorts. “Captain Lightfoot” was written by, and based upon a novel by, W.R. Burnett, who basically created the modern gangster tale (“Little Caesar”), and the modern heist tale (“The Asphalt Jungle”), and whose screenwriting credits include 1932’s “The Beast of the City,” starring Walter Huston as a police chief who takes the law into his own hands. That movie is often cited as a forerunner to, yes, “Dirty Harry.”

Bigger than ever

I’m glad I finally got around to watching “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot.” It’s one of those movies my cooler friends saw as kids and talked up all the way through high school. I avoided it for some reason.

It’s good. There’s artistry here. Some of the shots are just beautiful, and the main relationship is fun and off kilter. I love George Kennedy’s line by the river, “Boy, do I feel old,” as he sits there, crumpled. Clint plays a Clint character, but looser than normal. Apparently that was one of Cimino’s directives to Jeff Bridges: Keep Clint laughing.

Bridges would be the film’s only Oscar nomination, for supporting, and I assume he got this because of the scenes near the end, when Lightfoot is kicked in the head and begins suffering the effects of a traumatic brain injury. He starts slurring his words, his arm goes numb, and half his face goes slack. It’s impressive. Even so, for most of the film, I found Lightfoot annoying. He thinks he’s funnier than he is, wilder than he is. He’s just too much. When he spots that female motorcyclist and asks about her hot pants, and, mid-ride, she takes out a hammer and starts pounding dents into his truck, then rides off giving him the finger, he shouts, “You freak!” A second later he adds: “I love you, come back!” I just didn’t buy it. Or care for it. I don’t think there’s many guys like that, and the guys that are kind of like that I find boring.

Most of the movie is itinerant, going from place to place seemingly without reason. It opens on a small one-room church, where, from outside, we hear the singing of a hymn, even as a big American car drives by then doubles back. The driver is Red Leary (Kennedy), who enters the church and starts shooting at the preacher (Eastwood, a grifter in glasses and greased hair), who flees through nearby cornfields. At the same time, elsewhere, Lightfoot steals a white Trans-Am off a used-car lot, and this is our meet-cute for the title characters: Thunderbolt flags down Lightfoot’s car, then hangs on for dear life.

Why do they stick together? I guess the kid comes to admire Eastwood’s Korean war heroism, revealed by and by, while the kid amuses Eastwood. He likes his joie de vivre. They steal a car from a bickering middle-class couple at a gas station, shack up with two girls at a motel (one is Catherine Bach), eat at a diner. Red and his affable partner Eddie (Geoffrey Lewis) keep showing up: at a bus station, shooting at them outside the diner, and then in the backseat of their car outside a schoolhouse. How does Red keep finding them? No explanation. He's just there. Of all the places to be, he guesses right, again and again. This is one of the many reasons I’d make a bad Hollywood screenwriter: I want explanations for what 95% of the audience doesn’t even think about. Just keep it moving, kid.

After Red beats up Lightfoot, and Thunderbolt beats up Red, we get the full story to this seeming itinerancy. Years earlier, Red and Thunderbolt were part of a gang that pulled a successful bank robbery, but then: 1) their gang leader died; 2) the press reported the money had been found; 3) Red went to prison on an earlier charge and assumed Thunderbolt betrayed him. He’s finally set straight on this by the ass-whooping, I guess, and intrigued to learn the money was never found, then bummed that they stashed it in a one-room schoolhouse that no longer exists. A new, modern schoolhouse had been built in its place.

It’s the kid who figures out the next step and the rest of the movie. Why not just rob the bank all over again? They know it worked once. Just do it again. Both Thunderbolt and Eddie are initially amused at the thought—particularly since Red thinks it’s screwy—but then realize, “Yeah … Why not?”

To get the money for supplies, they take working class/service sector jobs: Eastwood as garage mechanic, the kid as landscaper, Red as janitor, Eddie as ice cream vendor. Among the things they buy? A 20 millimeter Oerlikon cannon to bust through a wall. It’s both used by Thunderbolt and how he got his nickname. And though it’s a small part of the film, it’s also all over the movie posters. You thought a Magnum .44 was big? Check this shit out. It’s the movie’s unspoken tagline: Eastwood’s dick is back, and it’s bigger than ever!

Buying the serendiptiy

What really stands out, 50 years later, is the misogyny. This is the era after the sexual revolution but before women’s lib went mainstream—or before most men took a long dark look at themselves—so women are just there to ogle and fuck and forget. Their bodies are there to be monetized by Hollywood. On the landscaping job, a housewife teases/taunts Lightfoot by standing in front of him (and us) stark naked. There’s Catherine Bach and her friend, who, post-coital, cries rape when Eastwood won’t give her a ride home. There’s rape jokes. Our two heroes ogle a waitress’ ass and Red ogles two teens in the act. That female motorcycle rider had the right idea.

The second heist works but the attempt to avoid detection in a drive-in goes awry when the ticket lady hears Red and Eddie in the trunk and call the cops. I assume she thinks they’re trying to sneak into the drive-in—as we did as teenagers? For some reason, the cops put two and two together rather quickly. Cue car chase and car crashes. The affable Eddie is shot and pushed out of the trunk by the increasingly nasty Red, who knocks out our title characters and takes the money. He kicks Lightfoot several times in the head for good measure, which is what leads to the brain damage. But Red gets his. Trying to escape, he crashes into a dept. store and runs into the vicious dogs he’d heard about as a janitor. They tear him apart.

As for our heroes? Back to itinerancy. They hitch rides and wander around, Lightfoot increasingly addled. Then we get a kind of glorious moment: In the middle of nowhere, they come across the one-room schoolhouse, which had been relocated as a national landmark, and find the original bank money behind the blackboard. Sure, you have to buy the serendipity of it all, not to mention that in moving the schoolhouse the blackboard was never moved or fell off. But it’s a fun idea: It’s not gone, it’s a landmark. Thunderbolt then buys the Cadillac he always wanted and in the manner he wanted (with cash), but at this point it’s too late for Lightfoot. He dies in the cradle of Thunderbolt’s arm. I couldn’t help but think of “Midnight Cowboy.” Cue Paul Williams.

The movie did well at the box office—17th-best for the year—but Eastwood felt it should’ve done better and blamed United Artists’ promotional campaign and never worked with them again. I’ve also read he felt upstaged by Bridges and felt he too deserved an Oscar nomination. To which I'd said: no. You're good, Clint, but not Oscar good. A man’s got to know his limitations.

Thursday May 13, 2021

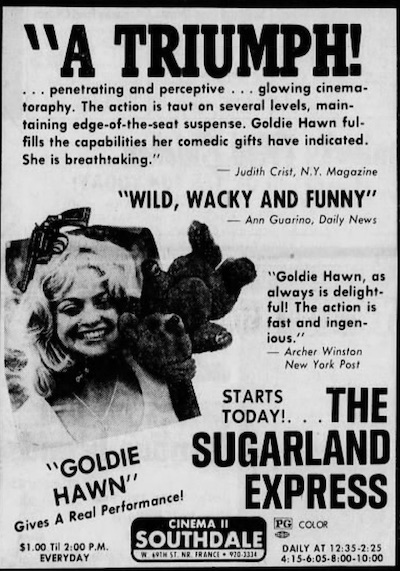

Movie Review: The Sugarland Express (1974)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I caught this for the first time on HBO the other night and liked parts but didn’t believe the brunt of it. Turns out the thing I didn’t believe the most was true.

“The Sugarland Express” was, of course, Steven Spielberg’s feature-film debut and he already seems like a pro. Certain shots—through windows, or with the principles off center—look great. I do miss this period of American filmmaking when they would use obvious locals for bit parts. The adoptive mother, Mrs. Looby, was played by a professional actress, Louise Latham, but the part of her husband went to Merrill Connally, a county judge and the brother of Gov. John Connally. Apparently the baby that was the focus of everything, baby Langston (son of producer Richard Zanuck and Linda Harrison), took to Connally but not to Latham, which is why Mr. Looby winds up holding him more often. Spielberg also took to Connally and offered him a role in his next movie: playing the mayor of Amity Island in something called “Jaws.” Connally turned him down, saying the part “sounded pretty poor.” Of course, Murray Hamilton got it and did everything with it.

Anyway, I miss obvious locals in bit parts. Bring that back, filmmakers.

Adorbs

Based on a true incident, “Sugarland” is definitely of its time. I was 11 when it was released and I remember the cool, older kids going to see it and talking about all the car crashes. It has a “Stick it to the Man” vibe that was prevalent then—one of the many bastard children of “Bonnie and Clyde.” Despite that, the Man comes off not poorly, while the kids ain’t exactly alright. They’re not the brightest bulbs in the world. Almost everyone’s sweet-natured but we still get this disaster.

The movie opens with Lou Jean Poplin (Goldie Hawn) visiting her husband, Clovis (William Atheron, 14 years before he became the jerky TV journalist in “Die Hard”), in prison. Sorry, in pre-release. He has just four months of easy time left, but she’s there to break him out. Their baby has been taken away by the county and adopted by the Loobys, and she wants him back now. So she bullies Clovis into sneaking out during a family prison/pre-release gathering.

The movie opens with Lou Jean Poplin (Goldie Hawn) visiting her husband, Clovis (William Atheron, 14 years before he became the jerky TV journalist in “Die Hard”), in prison. Sorry, in pre-release. He has just four months of easy time left, but she’s there to break him out. Their baby has been taken away by the county and adopted by the Loobys, and she wants him back now. So she bullies Clovis into sneaking out during a family prison/pre-release gathering.

Goldie is adorable here—she wasn’t yet 30—but Lou Jean is a piece of work. First she bullies Clovis into breaking out. Then she panics when a state trooper, Slide (Michael Sacks, Billy Pilgrim of “Slaughterhouse Five”), pulls over the elderly couple with whom they’ve hitched a ride—for going 25 on the highway—and she hops into the front seat and drives away, putting the cops on their tail. Slide gives chase and Lou Jean crashes the car. But when he carries her seemingly unconscious body from the wreck, she takes his gun, and they take him and his patrol car hostage, then drive to Sugarland to get their baby. A day later, when they arrive at the Looby home after everything else, she bullies Clovis into going in by himself even though none of it feels right and Slider himself warns against it. Sure enough, snipers are inside, and Clovis is killed. If not for his wife, Clovis would still be in pre-release, with four months minus a day left of easy time. Instead, he’s dead.

But Goldie is adorable.

The Poplins take Slider hostage about 20 minutes in, and within five or 10 minutes have dozens of patrol cars following behind them, moving slowly and respectfully down the highway. It’s like a precursor to the O.J. Simpson freeway chase. My thought was, “There’s 80 minutes left. What’s the rest?” Just that, it turns out. This slo-mo car chase, with ultimately hundreds of cars behind them, and a benevolent Capt. Tanner (Ben Johnson) ensuring that no wrong moves are made and no lives hopefully lost. It’s the titular Sugarland express, and it’s the part I didn’t quite buy. At the least, they exaggerated the number of cop cars following them.

Nope. According to accounts at the time, and more recently, it was more than 100 patrol cars, a blue caravan crawling across southern Texas. It’s a lot of the other stuff that’s fictional:

- Clovis (real name: Bobby Dent) wasn’t in prison at the time, so Lou Jean (real name: Ila Fae) didn’t bust him out.

- It was Bobby’s idea to kidnap a highway patrolman (real name: J. Kenneth Krone), and it was simply to get a ride, not to get their baby.

- There were two children involved, not one, and they were Ila Mae’s from a previous marriage, not both of theirs, and they were living with Ila Mae’s parents in Wheelock, Texas, not with foster parents in Sugarland, and the goal was just to see them, not take them.

- They didn’t becomes celebrities whose car was mobbed en route.

- All three principles, Bobby, Ila Fae and Trooper Krone entered the home in Wheelock, where Bobby was killed by Sheriff Sonny Elliott of Robertson County and FBI agent Bob Wiatt.

I get some of the changes. You’ve got to give them a goal at the outset. But the county taking the woman’s baby is a movie trope going back to silent films: Surely there were better ideas? And why give all of the man’s bad decisions to the woman? I guess because Goldie was the star. That's what you get when you're the star. Welcome to the party, pals.

Crashes and character

Goldie is great—completely naturalistic, not a false note—and I like the slight odd vibe from Sacks as Slider. And of course Ben Johnson does his Ben Johnson thing.

According to Wiki, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert (pre-“Sneak Previews”) were both lukewarm on Spielberg’s debut, each giving it two and a half stars. Siskel wrote, “‘The Sugarland Express’ asks us to care for Clovis and Lou Jean because they are thick-skulled and because, presumably, every mother has an inherent right to raise her own baby. It doesn't work.” Yep. Ebert wrote, “If the movie finally doesn’t succeed, that’s because Spielberg has paid too much attention to all those police cars (and all the crashes they get into), and not enough to the personalities of his characters.” Yep again. But poor Roger. Ignoring the characters for the crashes is about to enter a new, dominant period—one that has yet to end.

Wednesday March 17, 2021

Movie Review: Midway (1976)

WARNING: SPOILERS

There’s a great story about the screening of a rough cut of “Star Wars” for close friends of George Lucas in late 1976 or early 1977. It was early enough in the process that footage from World War II movies still substituted for the special effects-laden battle sequences. It didn't go well. Afterwards, there was some polite applause but a great deal of awkwardness. Most assumed the movie would bomb. Some compared it to “At Long Last Love,” which had sunk Peter Bogdanovich’s career the previous year. But one friend spoke up for it. “That movie is going to make a hundred million dollars,” Steven Spielberg said, “and I’ll tell you why: It has a marvelous innocence and naïveté in it, which is George, and people will love it.”

I thought about that story during this film because of the WWII footage. What Lucas used as temporary filler, “Midway” used for its theatrical release. According to IMDb:

I thought about that story during this film because of the WWII footage. What Lucas used as temporary filler, “Midway” used for its theatrical release. According to IMDb:

- Most the Japanese air raid sequences are from “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (1970)

- Scenes of Doolittle’s Tokyo raid are from “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo” (1944)

- Most dogfight sequences come from 1942 newsreels

- Several action scenes were taken from “Away All Boats” (1956)

You can tell, too. “Midway” went with an All-Star cast and grainy stock footage.

Rochefort dressing

The movie begins both well and poorly. Hal Holbrook plays Cmdr. Joseph Rochefort, a goofily cheery cryptographer who, at first glance, has a bit too much of the ’70s in him—thickish hair, moustache, bathrobe, like he’s the intelligence version of Hawkeye Pierce—but some of this is accurate. According to Wiki: “ He often wore slippers and a bathrobe with his khaki uniform and sometimes went days without bathing.” There are internal arguments among the U.S. military brass about where Japan will strike next, and Rochefort tells Admiral Nimitz (Henry Fonda) that the chatter his team hears keeps using the code “AF,” which he thinks is Midway. Other military leaders assume the next big attack will be the Aleutian Islands or even the west coast of the U.S., so a test is proposed: they send out a fake message about a water supply failure on Midway. Sure enough, the Japanese radio about water supplies on “AF.” The surprise the Japanese enjoyed at Pearl Harbor will now belong to the Americans.

I like all that. Unfortunately, the movie also includes is a fictional subplot that is the stuff of soap opera. Charlton Heston plays Capt. Matt Garth, the estranged father of fighter pilot Tom Garth (Edward Albert), who is looking to reconnect with his son. The fact that Matt is divorced feels out of time—that was a ’70s conversation, less a ’30s one. And then there’s Tom’s dilemma. He has to tell his old man: 1) his girlfriend, Hakuro (Christina Kokubo), is Japanese; 2) she and her parents are being held as subversives; and 3) can he help free them? When Matt objects, Tom accuses him of racism. Matt, in that Heston way, says he’s not racist, it’s just that his son’s timing is lousy; then he spends most of the rest of the movie trying to free them. I can’t even remember if he does, to be honest, and none of this is helped by the acting from Heston and Kokubo. Oh, and it turns out that her parents object to the union anyway since they don’t want Hakuro marrying outside her race. So who’s the racist now, huh? That’s the vibe.

Most of the U.S.-side of the cast consists of stars from the 1930s (Fonda), ’40s (Robert Mitchum in a cameo as Admiral Halsey),’50s (Heston and Glenn Ford) and the ’60s (James Coburn, Cliff Robertson). Plus a few young bucks who gained fame later: Dabney Coleman, Tom Selleck, Erik Estrada. We also get an uncredited cameo from Miami Dolphins running back Larry Csonka.

For the Japanese side, it’s almost every Japanese-American TV actor of the time: James Shigeta, Pat Morita, John Fujioka, Dale Ishimoto and Robert Ito. Plus the big gun, Toshiro Mifune, as Fleet Admiral Yamamoto. Unlike in “The Gallant Hours” with James Cagney, filmed 16 years earlier, the Japanese are forced to speak English here, but apparently Mifune’s English was so difficult to understand they dubbed him with Paul Frees, who also voiced the Burgermeister Meisterburger in Rankin/Bass’ “Santa Claus is Coming to Town.”

They did this to Mifune. Can’t make that stuff up.

The American race

The Battle of Midway is considered a turning point in the war in the Pacific. The Japanese lost four fleet carriers and a heavy cruiser, 248 airplanes and more than 3,000 men. The U.S. lost the carrier Yorktown and a destroyer, 150 aircraft, and 307 men. American morale went way up. Plus our industrial capacity far outstripped theirs. We could replace things, they couldn’t.

As for the soap opera: In battle, Tom Garth gets horribly injured but survives. Heston then steps in for the run at the final fleet carrier, succeeds, but crashes on the flight deck and dies. Glenn Ford closes his eyes in pain for his fictional friend, while Ensign George Gay (Kevin Dobson), the real-life sole survivor of Squadron 8, is pulled from the ocean. Tom, cleaned up and bandaged, is wheeled on a gurney past Hakuro, whose face reveals … who knows? Then Nimitz and Rochefort give us our coda as a large group of people, obviously pulled from some mid-1970s Hawaiian tourist attraction, mingle behind them. Nimitz wonders aloud how they were so successful when the Japanese had so many advantages. “Were we better than the Japanese or just luckier?” he asks. That, too, feels like a ’70s question—something to be pondered after the war is over—rather than spoken aloud in June 1942. Either way it goes unanswered.

Kind of. The movie’s final afterword is a quote from Churchill:

“The annals of war at sea present no more intense, heart-shaking shock than this battle, in which the qualities of the United States Navy and Air Force and the American race shone forth in splendour.”

The American race. Don’t hear that much anymore.

I first saw “Midway” at the Boulevard Theater in Minneapolis when it was released in 1976, and I remember being confused. Wait, there was a time when we were losing World War II? That was news to my 13-year-old self. The huge cast, many of them unfamiliar (I didn’t know from Glenn Ford or Robert Mitchum), as well as the grainy battle scenes didn’t help me find any kind of clarity, either. I guess I was hoping that this second viewing, 45 years later, might reveal some forgotten or hidden charms.

All-Star cast; extras pulled from the gift shop.

Tuesday October 08, 2019

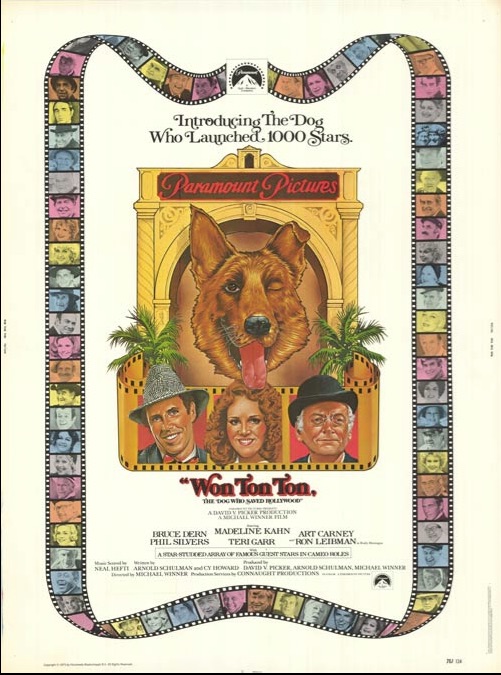

Movie Review: Won Ton Ton: The Dog Who Saved Hollywood (1976)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Is “Won Ton Ton: The Dog Who Saved Hollywood” the worst movie ever made?

It’s a comedy that has zero laughs. Zero. And it has Madeline Kahn in it. I didn’t think it was possible for Kahn to be this not-funny but everything she does falls flat. Kudos to Michael Winner, who took time off between directing rape scenes in “Death Wish” movies, for directing her in this.

It’s a comedy that has zero laughs. Zero. And it has Madeline Kahn in it. I didn’t think it was possible for Kahn to be this not-funny but everything she does falls flat. Kudos to Michael Winner, who took time off between directing rape scenes in “Death Wish” movies, for directing her in this.

It’s a heartless film. Every human being in it is worthless. Women want stardom, and will do whatever to get it; men want power and women, and will do whatever to get both. Near-rape scenes are treated lightly, as are two instances of near-child porn. We get jokes at the expense of the Chinese, Eskimos and “faggots.” Stepin Fetchit makes a cameo as a tap-dancing butler. Yes, it's racist and homophobic, but the greater insult is to the whole of humanity. It insults and condemns us all.

Everyone’s awful

It’s 1923 and Estie del Ruth (Kahn) is a starving actress in silent-era Hollywood who doesn’t even have enough money for the bus to go to a studio for an interview with a director. Instead, she hitchhikes in the manner of Claudette Colbert in “It Happened One Night”—by lifting her skirt. Except, since it’s Winner, and filmed in the 1970s, she’s much less discreet. One car screeches to a halt but he’s rear-ended by the guy behind him, who is rear-ended by ... etc. Four-car pileup. And as the soundtrack gives us a Keystone-Comedyesque rag filtered through ’60s sex comedies, Kahn mugs, hides behind some garbage cans, and mugs some more, while the drivers, all dressed in white for some reason, fight each other. It’s supposed to be reminiscent of slapstick comedies, but it’s so poorly choreographed it’s just confusing. Kahn’s reactions are just as confusing. Is she amused? Self-satisfied? What’s going on here?

That’s when, from the garbage can she’s hiding behind, a German Shepherd—whom we’ve seen engineering an escape from a dog pound—rises and licks her nose. That’s their meet-cute.

Except almost nothing about their relationship is cute. He loves her but she wants stardom. Does she even like the dog who does everything for her? It’s kind of sad.

When she gets to the studio, for example, the director she meets is actually a stagehand who gets her in a back room, where his intentions are obvious. She’s willing to go along if she gets a starring role—but she wants the quo before she surrenders her quid—and he can offer nothing; so he attacks her. It’s the dog to the rescue. In doing so, he becomes a star—this universe’s Rin Tin Tin. And since he only follows Estie’s instructions, she has to be his onset trainer. She resents this. She’s kind of awful about it.

So is her vagueish boyfriend, grifter-director Grayson Potchuck (Bruce Dern), who takes credit for the Won Ton Ton phenomenon while promising Estie he’ll get her a big role in his next production. He never does. Or just as he’s doing so, just as he’s convincing the studio boss, J.J. Fromberg (Art Carney), to include Estie in a movie with Won Ton Ton and Rudy Montague (Ron Leibman)—this universe’s Rudolph Valentino—Estie, in an amazingly stupid coincidence, runs into Montague at a theater where one of his pictures is playing. He’s in drag. To avoid fans? No, he’s a drag queen. And he’s so taken with Estie he demands she co-star in his next picture.*

(*The pitch is that Montague will play Gen. Custer and he and Won Ton will save the regiment. Which leads to a conversation that is only interesting post-Quentin Tarantino:

JJ: Wait a minute. Custer got killed at the end.

Potchuck: So what?

JJ [pause]: You’re right. History’s not the Bible.)

So is Montague an OK dude? Nope. At the press conference introducing the Custer movie, Estie and Won Ton get more attention so he puts out a hit on his co-stars. Yes, a hit. That phone call is a master class in gratuitous vileness. When the hit man, Nick (Victor Mature), hears who it is, he turns to his moll and says, “It’s the fag.” Then when the call is over, we see, in the room with them, tied to a chair with thick ropes, a half-naked 2-year-old girl. He tells her he’ll let her go when the ransom is paid; then he puts her gag back in. It doesn’t have anything to do with anything—it’s just tossed in there. It’s like Winner thought: “This scene isn’t awful enough: What can I add?”

The hit doesn't go off, of course. Or Estie gets the upper hand and it turns cartoonish—with speeded-up motion and big “BOING” sound effects. Meanwhile Won Ton, in an attempt to rescue her, tries to jump through the wall like he’s able to do in his movies. Instead he just bangs off and whimpers. It’s painful to watch.

When the Custer movie bombs and fortunes turn 180 degrees. Potchuck (and Estie and Won Ton) lose their mansion and are forced to live in a cramped studio apartment with her friend Fluffy (Teri Garr). They try a Mexican porno film, but that bombs, too. So Fluffy and Estie become prostitutes.

Reminder: This is a comedy.

Since Won Ton Ton will attack any man kissing or pawing at Estie, she leaves him with a kindly older man (Edgar Bergen), who, it turns out, is a vicious dog trainer with a shitty two-bit show. She doesn’t tell the man that her dog is Won Ton Ton, the most famous dog in the world, and he doesn’t figure it out. He just whips Won Ton and locks him in a closet and has him sprayed with seltzer on stage. Won Ton, or the dog actor, looks genuinely hurt and confused here, probably because he was. Before long, he becomes a stray.

Reminder: This is a comedy.

Then Estie’s fortunes turn again. On the set of a Keystone-y cop comedy, Mark Bennett (read: Mack Sennett) extols the virtues of Estie in the Custer flick and makes her a star. But now she wants Won Ton back. She holds press conferences and offers a $5,000 reward.

At her wedding to Potchuck, guess who shows up? Won Ton! Yay! The end. No, sorry. Despite her very public search for him, not to mention the fact that he’s the most famous dog in the world, Won Ton is shooed out of the chapel; and despite his normally resilient personality, he accepts it; he slumps away with head bowed. Then we see him being fed liquor by cackling bums in a dark alleyway. Then he tries to kill himself by:

- putting his head in a gas oven (Keye Luke tosses him out of his kitchen)

- lying in the middle of the road (a car runs over him without touching him)

- putting his head in a noose and knocking the chair away (he slips and falls to the floor)

Reminder: This is a comedy.

Winner’s taste

The cameos of silent-era or Golden-Age stars was one of the movie’s selling points, but sadly “Won Ton” wound up being the last screen appearance for many of them. From IMDb’s trivia section:

- Final film of Stepin Fetchit

- Final film of Rudy Vallee

- Final film of George Jessell

- Final film of Ann Rutherford

- Final film of Andy Devine

- Final film of Johnny Weismuller

- Final film of William Demarest

It’s like a hit list. It’s like Michael Winner killed them all.

Why do I keep blaming Winner? Why not screenwriters Arnold Schulman (“Goodbye, Columbus”) or Cy Howard (“Smothers Brothers”)? Or someone at Paramount Pictures? Because by his own admission Winner was a bit of a martinet. “You have to be an egomaniac about it,” he said of directing. “You have to impose your own taste. The team effort is a lot of people doing what I say.” Some actors have gone further; they say he was a virtual sadist on set.

In the end, of course, Estie and Won Ton are reunited, but it’s just so stupid. Won Ton shows up at Estie’s new place overlooking the ocean, but their butler—again, oblivious—shoos him away; then he throws rocks at him. Won Ton whimpers; then he tries to kill himself again by running into the surf. That’s when Estie finally spots him, and they’re all reunited, and cavorting in the surf. The press gets wind, talks up the next Won Ton Ton picture with Estie, but she says the dog isn’t Won Ton; it’s another dog. She lies so he won’t have t do movies anymore. Because that was always the problem.

This stupid movie can’t even get its movie history right. It keeps referencing Clara Bow as the industry’s big star when that was later—1926 or '27. It shows Keystone Cop movies being filmed when that was earlier—the 1910s. Potchuck has a recurring gag pitching movie ideas that get shot down even though they’re the plots of later box-office hits: “It’s about a giant shark terrorizing an entire New England town,” he says, or “A little girl gets possessed by the devil.” He also pitches a musical about a girl who “gets caught up in a tornado and she winds up in this strange land with a scarecrow and a guy made out of tin.” Immediate thought: Musical? In the silent era? And why doesn’t anyone say “You mean ‘The Wizard of Oz’?” Since, you know, it was known. It was a famous series of books that had already been made into a movie three times: 1910, 1914 and 1925.

I haven’t even mentioned how “Won Ton Ton” gets his name. Early on, Potchuck is pretending the dog is his even though he keeps calling him different things: Rex, Fido, etc. So J.J. asks for his name.

Potchuck: Well, his name is .... All right, I mght as well tell you the whole story. When I was working on the railroad back there in ’21, there was this Chinaman bit by a rattlesnake right here in the throat. He lay dying in my arms, and just before he died, he looked up at me so sadly and said, [in pigeon English] “You take care of my dog, no matter what happen. Because he like my velly own boy.”

JJ: Look, I’m not interested in Chinamen, they don’t go to many movies. What the hell is the dog’s name?

Potchuck [dazed]: Won Ton Ton.

JJ [dubious]: Won Ton Ton.

And that’s the joke.

At the Custer screening, one fed-up moviegoer shouts, “This picture could kill the movie business!” Truer words, brother.

Thursday April 27, 2017

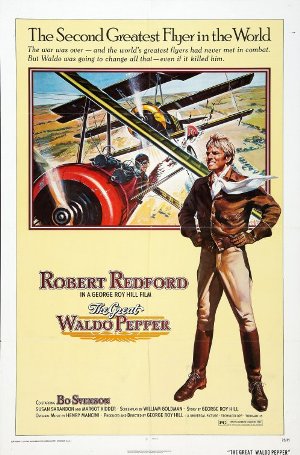

Movie Review: The Great Waldo Pepper (1974)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Patricia made a face the other night when I suggested watching Robert Redford in “The Great Waldo Pepper,” but it turned out she’d never seen it. I had. Three times? Five? More? Never in the theater, just on TV or cable, but probably not in 25 years. Most of the story was still in my head but I was curious how it had aged. Or how I had.

“Waldo” is lesser Redford from his glory period. He was the biggest movie star in the world, and from’73 to ’76 he starred in the following:

- “The Way We Were”

- “The Sting”

- “The Great Gatsby”

- “The Great Waldo Pepper”

- “Three Days of the Condor”

- “All the President’s Men”

Only “Gatsby” sucked. Redford was all wrong to play a man hopelessly in love; that’s not his character. He’s the one women are hopelessly in love with. Think Barbra in “The Way We Were,” Mary Tyler Moore weekly stuttering his name, and the prison guard’s wife in William Goldman’s book “Adventures in the Screen Trade,” who tells her husband she would gladly “get down on her hands and knees and crawl just for the chance to fuck him one time.” Again: She tells her husband this. So, yeah, not Gatsby.

Only “Gatsby” sucked. Redford was all wrong to play a man hopelessly in love; that’s not his character. He’s the one women are hopelessly in love with. Think Barbra in “The Way We Were,” Mary Tyler Moore weekly stuttering his name, and the prison guard’s wife in William Goldman’s book “Adventures in the Screen Trade,” who tells her husband she would gladly “get down on her hands and knees and crawl just for the chance to fuck him one time.” Again: She tells her husband this. So, yeah, not Gatsby.

Which raises a question: What was the essence of the Redford character during his heyday? Into his late ’30s, he was still playing the ingénue, still being shown the ropes by the like of Paul Newman and Jason Robards. And Barbra. His character has promise and his character often fails. That happened to be the essence of America at the time—how we viewed ourselves. “The Way We Were” actually makes the comparison explicit: “In a way he was like the country he lived in: everything came too easily to him.” And then it didn’t. That’s the point of the ’70s. When everything stopped being easy.

Pepper vs. Kessler

“Waldo Pepper” begins in the late 1920s, and while life isn’t exactly easy for the title character, it is freewheelin’. He’s a young blonde-haired hunk of man barnstorming around Nebraska, and selling simple folk on the thrills of aerial adventure. For some reason the movie posits him as a kind of charlatan, a bullshit artist. He’s supposed to come off a bit like Redford’s grifter in “The Sting,” but when you think about it he is actually selling something worthwhile: a chance to see the world from the sky. In the 1920s, that’s the stuff of gods.

The bullshit comes when he tells the local yokels about his dogfights during the Great War against German ace Ernst Kessler (cf., Ernest Udet): how he and four other guys had him in their sites but Kessler shot them all down, all except Pepper, whom he fought to a standstill until Pepper’s guns jammed. Kessler saw this, saw his opponent was helpless, but he didn’t take advantage. There was honor in the skies. He pulled up alongside him, saluted, and continued back to Germany. A great story. A true story. But not Pepper’s story. He didn’t make it into battle; he was still training recruits at the time. When he’s caught in the lie by his rival Axel Olsson (Bo Svenson, surprisingly good), his lament is: “It should’ve been me.”

That’s the tragedy of his life when we first meet him: He thinks he’s one of the best but never got the chance to prove it. The tragedy of the rest of the movie is that that life, the life we first see him living, disappears. He becomes increasingly saddled—first with a partner (Axel), then a flying circus (Doc Dihoefer’s), then federal regulations (former pal Newt, played by Geoffrey Lewis). But the real problem is other people’s ennui. Planes become everyday, so the crowds disappear, so the stunts have to become bigger and more dangerous to draw them back. The tension is between the crowds, who demand blood, and the feds, who demand safety, with our heroes caught in the middle.

The crowd gets what it wants. Axel’s movie-loving girlfriend, Mary Beth (Susan Sarandon), is pulled into wing-walking to add sex to the stunt; but despite her visions of grandeur, of becoming the “It Girl” of the skies, she freezes on the wing. Despite Herculean efforts to save her, she falls. (Patricia was legitimately, vocally shocked by this; she forgot what ’70s movies were like.) More gruesomely, Pepper’s pal, Ezra Stiles (Edward Hermann), finally finishes the plane that might be the first to perform an outside loop, but at this point, because of the Mary Beth tragedy, Waldo is grounded by the feds, so Ezra tries it himself. He’s not pilot enough to pull it off, and on the third try crashes. Trapped by the plane, the yokels gather around, some with cigarettes, and the leaking gas is ignited. Ezra is burned alive while everyone watches. This traumatized me as a kid, not least because I didn’t get it. Why did everyone just stand there? My father tried to explaining it to me, but, to be honest, as an adult now, 54, I think it’s part of the movie’s bullshit. It was the era’s extreme anti-populist message, and it feels false to me. And I’m a cynic.

Eventually, Waldo follows Axel to Hollywood, becomes a stunt man, then finally meets the great man, Ernst Kessler (Bo Brundin), on the set of a “Wings”-like aviation epic about Kessler’s dogfights. They talk, lament the passing of better days, then go off-script in the skies so they can dogfight without the guns in one final moment of freedom. They essentially kill themselves in the skies. It’s a dumb ending. It makes Thelma and Louise seem like they were really thinking it through.

A regular August Wilson

You know what I kept thinking watching this? Charles M. Schulz. He grew up in the Midwest (St. Paul, Minn.) in the 1920s. He could’ve been that kid getting gasoline for Waldo’s plane. He certainly bought into the romance of it all, then updated it in the 1960s with Snoopy and his Sopwith Camel, which is where I picked it up. Everything I learned about the Great War I learned from a beagle.

Was it Redford specifically, or the popular cinema at this time, that kept looking backwards, ceaselessly, toward the past? From ’73 to ’85, his only movies with contemporary settings were the two political thrillers above and “Electric Horseman” in 1979. Otherwise he’s a regular August Wilson:

- 1910s: “Out of Africa”

- 1920s: “The Great Gatsby”; “The Great Waldo Pepper”

- 1930s: “The Sting”; “The Natural”

- 1940s: “A Bridge Too Far”

- 1940s-50s: “The Way We Were”

- 1960s: “Brubaker”

A man out of time.

“Waldo” isn’t bad. Redford’s gorgeous, Bo Swenson is remarkably good, so is Sarandon. Writer-director George Roy Hill, a real aviation buff, gets the details right. It’s fun for an evening—Patricia liked it—but it doesn’t quite resonate. Like the bi-planes it’s filming, it just kind of drifts away.

Thursday March 02, 2017

Movie Review: The Towering Inferno (1974)

WARNING: SPOILERS

People often talk about the worst best picture Oscar winners of all time—I’m often one of them—but rarely do we get a discussion of the worst No. 1 box office movies of the year. The former indicts the Academy, the latter all of us. It’s so much more fun pointing fingers.

But if we were going to have such a discussion, the list would surely include the following:

- The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013)

- Spider-Man 3 (2007)

- The Grinch (2000)

- Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (1999)

And this one.

On some level, this one feels more unforgiveable, since the No. 1 movies surrounding it chronologically are still regarded as, you know, pretty fucking good: “The Godfather” in 1972, “Exorcist” in ’73, “Jaws” in ’75. We still watch those, own those, discuss those. “The Towering Inferno”? Part of that Irwin-Allen-produced, All-Star Cast, disaster flick era, with “Airport” (No. 2 in 1970) “The Poseidon Adventure” (No. 2 in 1972), “Earthquake” (No. 4 in 1974), and “The Swarm” (died at the box office). And you say it was No. 1 in 1974?* Whaddaya know.

(* Box Office Mojo now lists “Blazing Saddles” as the No. 1 movie of 1974, but that’s only because the money it earned during a 2013 re-release. For decades, “Inferno” was No. 1.)

As a teenager in the 1970s, I didn’t see any of these disaster flicks. Maybe I caught bits when they showed up on “edited-for-television” TV, but I don’t think I sat through any of them. Particularly “Towering Inferno.” Planes and upside-down boats were one thing, but fire? The Fire Safety Program in 5th grade made me terrified enough. “Inferno” was the last thing I wanted to see.

Forty years later, though, I was curious. Just how bad was it?

When an “All-Star Cast” meant something

Pretty bad. It’s a soap opera. It’s like what “Love Boat” would become: different people come on board with their own little micro-dramas, then disaster strikes. Here it’s fire, there Gavin MacLeod.

As All-Star casts go, this one is pretty tight. The key is to mix old-timers and up-and-comers with current stars. Every decade after the silents is represented:

- 1930s: Fred Astaire, loose and athletic at 75.

- 1940s: Jennifer Jones, looking shellacked by plastic surgery; it’s her last film.

- 1950s: William Holden as the movie’s developer-villain, but apparently the nicest guy on the set.

- 1960s: Our headliners: Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, Faye Dunaway.

- 1970s: dishy newbie Susan Blakely and everyone’s favorite football player O.J. Simpson.

We also get TV stars of the ’60s (Robert Vaughn, Robert Wagner and Richard Chamberlain), along with one from the ’70s: Bobby Brady himself, Mike Lookinland, acting in scenes with Newman and Dunaway. OK, “acting.”