Wednesday February 17, 2016

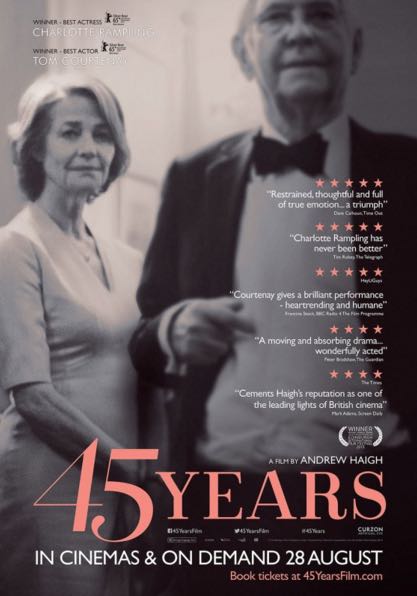

Movie Review: 45 Years (2015)

WARNING: SPOILERS

On the Monday morning before her 45th wedding anniversary, which will be celebrated with friends on Saturday, Kate Mercer (Charlotte Rampling) goes for a walk in the flat fields of the English countryside with her dog Max, says hello to the postman, a former student, then greets her husband, Geoff (Tom Courtenay), still unshaven and in his bathrobe, in the kitchen. One of the letters in her hand is for him. The contents of it will affect the next five days, and taint their previous 45 years.

“They found her,” he says.

From the trailer I thought the missing person was their daughter, but it’s Katya, his first love. In 1962, he’d been hiking with her in the Swiss Alps when she’d fallen into a fissure. Thanks to global warming, the glacier melted enough that her body, perfectly preserved, was visible if unreachable. It’s a good metaphor for first loves—preserved in ice, irretrievable—and in her late 70s Kate suddenly finds herself competing with a woman 50 years younger; with all of that cold perfection.

Variations in e minor

Their relationship changes subtly and immediately. Geoff tries to probe the depths of his feelings in solitude, which causes Kate to try to get closer. Biscuits in the backyard? Tea? Camera placement highlights this. In the frame, we often see her face, not his. Sometimes we don’t see him at all, as if he isn’t there anymore. In a way, he’s not. He’s visiting the attic in the middle of the night, going into town, mumbling to himself on park benches. Is he returning to Switzerland to see her body? He would like to, but at his age he can’t climb that mountain anymore. Another good metaphor for the past. So he stays where he is; but a fissure develops.

Their relationship changes subtly and immediately. Geoff tries to probe the depths of his feelings in solitude, which causes Kate to try to get closer. Biscuits in the backyard? Tea? Camera placement highlights this. In the frame, we often see her face, not his. Sometimes we don’t see him at all, as if he isn’t there anymore. In a way, he’s not. He’s visiting the attic in the middle of the night, going into town, mumbling to himself on park benches. Is he returning to Switzerland to see her body? He would like to, but at his age he can’t climb that mountain anymore. Another good metaphor for the past. So he stays where he is; but a fissure develops.

Like themes in a song, we keep getting variations on that awful moment in 1962. Geoff tells Kate he’d hired a guide, a German, who’d fancied himself a Jack Kerouac type. (Kate laughs, knowing how much Geoff dislikes Kerouac—which makes me like Geoff all the more.) Katya spoke German, too, Geoff no, so you get a sense of Geoff being left behind. He allowed himself to be left behind, literally; the other two hiked ahead. He talks about hearing Katya laugh, and how, in his jealousy, he hated her in that moment. Then he heard her cry out as she fell.

What Kate doesn’t explore (the movie either) is how much guilt Geoff must feel about all of this. If he hadn’t been sulking, he would’ve been walking with them; and if he’d been walking with them, would she have died? Is that what he’s doing on the park bench? Arguing against Katya? Kerouac? Himself?

A few days later, we get another variation when Geoff is in town and Kate ascends into the attic. I like how her dog Max whimpers as she prepares to go up, as if he knows there’s danger there, as if he knows this is not regular behavior. He knows the man goes up the ladder, not the woman. But up she goes, into his past. I also like how, in the opening credits, white type against a black screen, we hear a whirring and a clicking. I thought, “Slides?” Yes. After going through his old notebook, its pages mottled and thickened by age, she views the slides he’s been viewing. It’s a great, silent scene: the blurred images of Katya on the right side of the screen, with Kate on the left, in focus, and hardening. She and Geoff have very few photos of themselves—her call—and no kids. Now she discovers Geoff has all of these photos of Katya, perfectly preserved; and in the slides, it’s obvious that Katya was pregnant when she died. So it’s not just his old love that’s forever frozen in the Alps but his unborn child. The slides contain the beginning of a life he tragically didn’t lead. Which makes Kate what? The life he tragically did?

(The pregnancy revelation does raise questions. Why were they hiking in the mountains if she was pregnant? And why the jealousy? Would Kerouac really have come on to a pregnant woman? Would Geoff really have been so jealous? Pregnancy is a different dynamic—woman as mother rather than sex object—so skews things a bit, even as it deepens them.)

More things in their careful world are changing. Each day, the first thing we first see is Kate walking the fields with Max. But by Thursday, no, and Friday she wakes to a note next to her: “I’ve taken the bus into town. Sorry.” Saturday, the day of their anniversary celebration, Geoff wakes her up with tea and breakfast. Now he’s the one trying to get close again—like biscuits in the backyard—and later we get an interlude. She’s digging in the garage and comes across some J.S. Bach sheet music. “Found it!” she calls out. Then she goes into the living room and plays it. But in the entire scene, we never see or hear Geoff. She’s calling out to no one, playing for no one.

How I knew

The Bach is an anomaly. The music we get for most of the movie, and which plays at their anniversary celebration, is ’60s pop. It’s “true love” music: “The only one for me is you/And you for me/So happy together,” etc. That night, in fact, they dance to “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes” by the Platters, which is about as lush and romantic a pop song as there is:

They asked me how I knew

My true love was true

Oh-Ohhhhhhhhhhh

I of course replied

Something here inside

Cannot be denied

But it’s the opposite of romantic here. By now Kate knows, or feels, that she’s not the true love of the song, so she hardens and stiffens in Geoff’s arms, even as he (compensating?) gets looser, loopier. You could say she’s dancing to some other woman’s song on some other woman’s anniversary. Because 45 years? Who does a black-tie celebration for that? That’s why the title of the movie is so perfect. The big one is the 50th, and that’s Katya’s. It’s been 50 years since she died. Is nothing Kate’s? Even their names: “Katya” is exotic, romantic; “Kate,” in comparison, can’t help but sound quotidian. It doesn't compare.

For all of the movie’s quiet power, though, I found myself disappointed in Kate. Almost everyone has their (albeit less tragic) past love, their Katya on ice, and part of aging, part of wisdom, is to accept that, and them. It’s to not buy into the bullshit of the pop song. Charlotte Rampling usually plays smarter, more wordly women.

Even so, “45 Years,” written and directed by Andrew Haigh (HBO’s “Looking”), from a short story by David Constantine, is the epitome of the quiet-but-powerful movie. It’s about what ties us to the past, and what divides us in the present. It’s the unknowability of the heart, and of the other person. It’s the misstep that isn’t righted.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)