Friday August 20, 2021

Louis Menand on Elvis, the Beatles, and Where the Hell Teenagers Came From

Elvis on the Dorsey Show. Radio didn't care about race, TV did.

I’ve been slogging through Louis Menand’s “The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War” for the past few months now, setting it down for another book, picking it up again when that book was finished, hoping it would get better or more interesting or more interesting to me. I liked the chapter on Orwell well enough, and the chapter on the sham of the beats, but once he got into the philosophers and the art world, well, I guess I put it down because I had trouble picking it up. Too much of it went over my head. But the other day I skipped a chapter to the one on music and “youth culture,” and … holy fuck. I wish I could buy people just this chapter.

I know a lot about Elvis and the Beatles, but not completely, and some of the angles Menand comes from are new. He doesn’t underline it, but each act presented its opposite face when performing. Privately, Elvis was polite and deferential, onstage he roared with rebellion. The Beatles flipped this script. Onstage, they were polite—bowing after each number—while in private and in press conferences, they were cheeky, rebellious, dismissive of authority. Press agent Derek Taylor talks about their fangs. Producer George Martin, the fifth Beatle, said they didn’t give a damn about anyone—that’s partly why he liked them. “They sang of love,” Menand writes; “they were loved by millions; ‘loveableness’ was the essence of their appeal. But they loved only one another.”

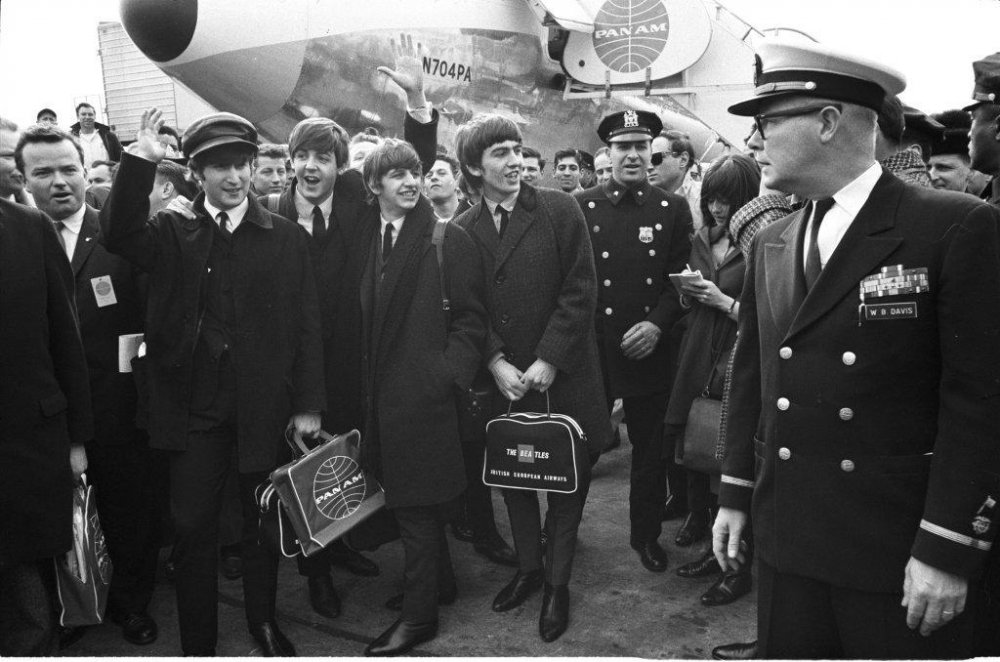

How the Beatles disarmed the press is well-known, and Menand calls one of the exchanges on Feb. 7, 1964, the day they arrived at JFK Airport and all hell broke loose, “sublime.” This one:

Q: What do you think of Beethoven?

Ringo: Great. Especially his poems.

Menand writes:

Some of the Beatles’ wit can be credited to the social style of working-class Liverpool life. Ringo, for instance, who was by far the least educated Beatle (childhood illnesses had kept him out of school for long periods), did not acquire his drollness with the mohair suit Brian Epstein accoutered him in. It was his natural manner of deflecting insults. The question about Beethoven was a genteel insult, and it is telling that he, the Beatle least likely to know much about Beethoven, should have had the quickest retort, and a retort to which no follow-up is possible.

He adds: “If Elvis Presley had had a month to think about it, he couldn’t have come up with that line.”

But it’s in the pullback into how teenagers became a thing where this chapter completely jazzes me. Where did teenagers come from? Hadn’t they always been? Not really. So why did they become a thing? Because high school happened. In 1900, he informs us, only 10.2% of 14- to 17-year-old Americans were in school. By 1940, it was 73%, and it kept growing. And that emphasis on education was specific to America. I’ve never heard this 1966 quote of John Lennon’s but it’s telling: “America used to be the big youth place in everybody’s imagination. America had teen-agers and everywhere else just had people.”

Teenagers happened in part because the family farm stopped happening: “In 1900, 38 percent of employed Americans were farm workers; in 1950, 12 percent were. By 1960, it was a little over 6 percent.” Then college was added. There was all this time, and money, and what do you do with it?

Menand goes into the copyright and financial battles between the behemoths ASCAP (founded in 1914) and BMI (founded in 1939), and how after World War II the FCC set out to license new, independent radio stations to create media competition. They were everywhere, and radios were increasingly added to automobiles. Menand gives us the birth of things. In 1948, Columbia issued the first 33 1/3 LP. Eight months later, RCA introduced the 45 RPM single. Phonographs, particularly for singles, became more affordable. Portable transistor radios began selling in 1953. Jukeboxes went from holding 24 records, to 100, to 500.

Why Elvis? R&B was breaking through, for both white and Black performers, and they were all played on the radio. Radio was integrated. TV segregated them again. “Many sponsors avoided mixed-race television shows,” Menand writes, “since they were advertising on national networks and did not want to alienate white viewers in certain regions of the country.” Plus TV is a superficial medium and Elvis was young, sexy, sneering. America and the world went nuts. Read George W.S. Trow on Elvis ’56.

Why the Beatles? I remember Philip Norman talking up how they were a cheery media distraction after tawdry or tragic events—the Profumo scandal in Britain, the JFK assassination in the U.S.—but Menand goes to other places. The baby boomers were coming into teenagehood, the business machinery was in place, and all the great rockers had died (Buddy, Richie), been busted (Chuck, Jerry Lee), or gone Hollywood (Elvis). “When the Beatles arrived in New York, the pop charts had been dominated by singers like Bobby Vinton, Frankie Avalon, and Fabian—the ‘teen idols’—and groups like the Four Seasons. Presley had not had a No. 1 single since April 1962; he would not have another No. 1 in the United States until 1969.”

Why the British invasion? I found this info fascinating:

Britain had more art colleges per capita than any nation in the world. The establishment of a National Diploma in Design, in 1944, lowered the bar for entry—probably all [John] Lennon had to do was to submit to an interview and show a portfolio of his drawings—and this led to an academically permissive environment. … Every British act that had a lasting impact on popular music in the 1960s had at least one member who attended art college: the Rolling Stones (Keith Richards and Charlie Watts), the Who (Pete Townsend), Cream (Eric Clapton and the lyricist Pete Brown), Led Zeppelin (Jimmy Page), the Kinks (Ray Davies), the Jeff Beck Group (Jeff Beck and Ron Wood, later with the Stones), the Animals (Eric Burdon), and Donovan.

My interest waned when Menand tries to say something meaningful about Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone magazine. But the rest of the chapter fucking rocks.

The Beatles arrive, Feb. 7, 1964, filling a huge gap.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)