Tuesday May 17, 2011

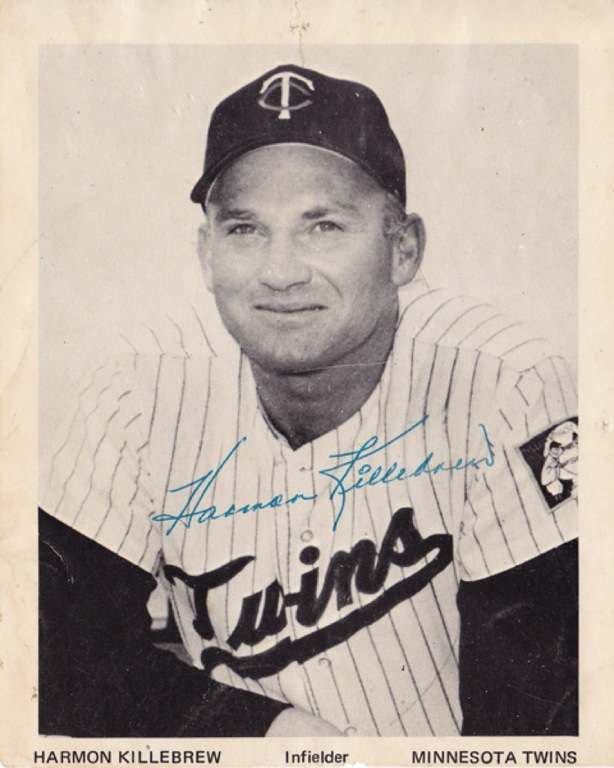

Harmon Killebrew (1936-2011)

“Speak softly and carry a big stick.”

I first read that phrase in reference, not to Teddy Roosevelt and his vision of America at the turn of the last century, but to my childhood hero, Harmon Killebrew, the Minnesota Twins first/third baseman during the 1960s and '70s. It was the title of a chapter on him in the book Baseball Stars of 1967. So much of life is like that: We learn the allusion before the reference point. But even when I learned a bit of history, of Roosevelt and the Monroe Doctrine, even then “Speak softly and carry a big stick” reminded me more of Harmon Killebrew. It fit Harmon Killebrew better. America never really spoke softly. There was always something loutish about our country. But Harmon Killebrew? In baseball, no one spoke more softly. No one carried a bigger stick.

Growing up in mountainless Minnesota, he seemed like a mountain to me: big and powerful and silent and ever present. Back then every August we’d have “Camera Day” at Metropolitan Stadium, in which, before the game, fans would line the warning track and get their pictures taken with their favorite players, who moved slowly around the field, in uniform, carrying bats or gloves. I’ve got photos of myself with Tony Oliva and Rod Carew and Cesar Tovar and Leo Cardenas but not with Harmon Killebrew. Photos with Harmon weren’t allowed. The Twins organization felt there would be such demand, the promotion would bleed into gametime. Instead, he’d moved slowly around the field, alone, his face placid, and we’d watch him from a distance, the way we’d watch a mountain from a distance. Invariably during that game he’d hit a homerun. Or two homeruns? Memories are faulty but I remember that a lot. We’d go to the park, sit in the sun on the wood benches along the left field foul line, and Harmon Killebrew would hit two homeruns.

Growing up in mountainless Minnesota, he seemed like a mountain to me: big and powerful and silent and ever present. Back then every August we’d have “Camera Day” at Metropolitan Stadium, in which, before the game, fans would line the warning track and get their pictures taken with their favorite players, who moved slowly around the field, in uniform, carrying bats or gloves. I’ve got photos of myself with Tony Oliva and Rod Carew and Cesar Tovar and Leo Cardenas but not with Harmon Killebrew. Photos with Harmon weren’t allowed. The Twins organization felt there would be such demand, the promotion would bleed into gametime. Instead, he’d moved slowly around the field, alone, his face placid, and we’d watch him from a distance, the way we’d watch a mountain from a distance. Invariably during that game he’d hit a homerun. Or two homeruns? Memories are faulty but I remember that a lot. We’d go to the park, sit in the sun on the wood benches along the left field foul line, and Harmon Killebrew would hit two homeruns.

This was around 1969, the year the Twins won the first A.L. West division championship, the year Harmon Killebrew won his first and only MVP award. He led he league in homeruns (49), RBIs (140), walks (145), intentional walks (20), and On-Base Percentage (.427). It was the seventh time in his career he hit over 40 homeruns in a season. He would do it once more, in 1970.

He deserved that award. He probably deserved to win it earlier. In 1962, he led the league in homeruns, with 48 (no one else was even in the 40s), and RBIs with 126, but he came in third in the balloting to two Yankees: Mickey Mantle, who had better percentage numbers but 200 fewer at-bats and 18 fewer homeruns, and Bobby Richardson, who hit .300 but never walked and never had much power. Folks focused so much on batting average back then. Bill James hadn’t come along yet to correct matters.

How much was he overlooked by the national press? He retired fifth on the all-time homerun list with 573, with only Aaron, Ruth, Mays, and Robinson ahead of him, and it still took him four years to get into the Hall of Fame. I was in college by then, focused on other matters, but it still bugged me. He played way away in Minnesota, where we speak softly, and so the Baseball Writers Association of America gave him only 59.6% of their vote in 1981, then dropped him to 59.3% in 1982, but ratcheted up to 71.9% in 1983, the year Brooks Robinson, in his first year of eligibility, and Juan Marichal, in his third year of eligibility, made the cut. Harmon would have to wait another year. And even then he finished behind Luis Aparacio and his .653 OPS. Harmon’s was .884.

By the 1990s I was living with several other people in Seattle, and one day, in the room of my friend Mike, I watched an ESPN rebroadcast of the 1971 All-Star Game in Detroit, which is memorable for the towering homerun Reggie Jackson hit off the transom in right field—one of the longest homeruns ever recorded for television. But the game turned out to be memorable for another reason. One after another, famous players, Hall of Fame players, hit homeruns: Johnny Bench in the 2nd, Hank Aaron in the 3rd, Reggie Jackson and Frank Robinson in the bottom of the 3rd. In the top of the 6th, Harmon entered the game, replacing Norm Cash at first base, and I was excited enough by that, happy enough to see that. Then in the bottom of the 6th, against Fergie Jenkins, Al Kaline led off with a single and Harmon came up and promptly hit a homerun to left. I went bananas. To Mike’s amusement, I began cheering as if the game were new, as if it weren’t 20+ years old. Roberto Clemente added another homerun in the 8th, and that was all the scoring, all on homeruns, all by six Hall-of-Fame players, including no.’s 1, 4, 5 and 6 on the then-all-time homerun list. Clemente’s homer went to center but all the others went to right, because the wind was blowing out to right. Only Harmon went deep to left, where the wind was blowing in. It felt like a piece of my childhood, watching that homerun. It always feels like a piece of my childhood when I see Harmon Killebrew swing.

Harmon died this morning, at the age of 74, of esophageal cancer.

A gentleman. You’re going to hear that word a lot in the next few days. In Bob Showers’ book, “The Twins at the Met,” that’s the word the other players use for him again and again:

Jim Kaat

Harmon was a gentleman, he was easygoing and he never lost his temper.Frank Quilici

Harmon was the first guy to shake my hand when I joined the Twins. He exemplifies class. Although he never sought the leadership role, Harmon was the quiet leader of the ballclub. He is probably the most respected Hall of Famer in baseball.Rod Carew

You want Harmon to be the role model for your child, because that’s how special he is. Even today, he’s still the same Harmon Killebrew that I met for the first time in 1964. He hasn’t changed at all.Bert Blyleven

When you talk about class, Harmon has to be no. 1. He’s the nicest gentleman I’ve ever been around.Tony Oliva

Harmon is so nice—he’s too nice to be a ballplayer.

My friend Jim Walsh provided a link to an old promo for the local Minnesota show “Kent Hrbek’s Outdoors,” in which Herbie went fishing with Killebrew; and Killebrew, to the camera, says something you don’t hear many people, let alone ballplayers, say. He says: “The reason we’re here on Earth is to love and help one another.”

Jim adds, “Turns out there is crying in baseball.”

My father, 79, gives tours at Target Field, and he says he already chokes up when talking about Harmon. He quotes Harmon’s Hall of Fame acceptance speech. As a kid, Harmon's mother complained that the boys were running around too much and ruining the grass. “We’re raising boys, not grass,” his father replied. That’s the line that gets my Dad. Now he worries how he’ll handle himself on upcoming tours. He hopes he doesn’t break down.

This is a sad month in a sad year for me. I attended a memorial in Minnesota in January, and two more this month in Seattle, all for friends who died too young. At some point you think you’re inured, particularly to the deaths of people you never knew personally, but that’s not that way. That’s not the way now anyway. This one still hurts.

Kent Hrbek, who provided his own Minnesota memories, was one in a long line of “Next Harmon Killebrews” the Minnesota Twins organization trotted out in the 1970s to try to make up for the void Harmon left behind. Craig “Mongo” Kusick was another. But the organization should have known. There is no next Harmon Killebrew.

Rest in peace, Harmon. Touch 'em all. And thank you.

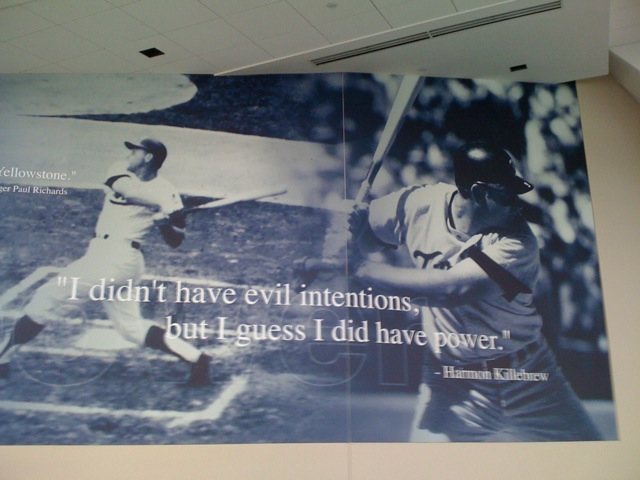

On the wall during the Target Field tour.

My nephew Ryan, 7, goes deep next to the statue of Harmon Killebrew outside Target Field in downtown Minneapolis: May 2010.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)