Friday August 16, 2013

George W.S. Trow and the Problem of the Final Failed Connection

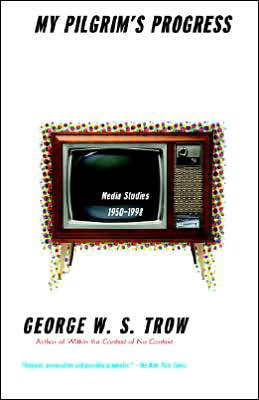

If you've been reading this blog lately you've noticed a few posts about George W.S. Trow, whose “Within the Context of No Context” I've practically memorized, and whose “My Pilgrim's Progress: Media Studies 1950-1998” I've been reading.

“Pilgrim's” is not as tight as “Context,” maybe because Trow was 20 years older when he wrote it, maybe because William Shawn wasn't around to edit it, maybe because Trow was already beginning to lose his mind. But there are many instances when Trow, as it with a wave of his hand, reveals the world to us. That thing that's been nagging at you for 20 years? This is why. Right here. He connects the disconnected.

Near the end of the book, in the chapter “My Life in Flames,” he gives us one such moment. He writes about the two houses in Hyde Park that are owned and maintained by the federal government: FDR's, of course, and a big marble palace built by Frederick Vanderbilt, grandson of Cornelius. Trow writes that it was FDR's idea to preserve the Vanderbilt home as a kind of testament to an awful period when too few people had too much of the money:

Near the end of the book, in the chapter “My Life in Flames,” he gives us one such moment. He writes about the two houses in Hyde Park that are owned and maintained by the federal government: FDR's, of course, and a big marble palace built by Frederick Vanderbilt, grandson of Cornelius. Trow writes that it was FDR's idea to preserve the Vanderbilt home as a kind of testament to an awful period when too few people had too much of the money:

At a time—it was wartime—when people had ration coupons; when people had family members who were dying abroad, when soldiers were receiving pay, and I don't know exactly what a G.I.'s pay was during World War II, but was it sometimes fifty dollars a month for a private?—and all of this sitting on top of the Great Depression; in the early 1940s, say, a big marble house built by a robber baron forty years before was—almost an object of terror, one wants to say; a lesson to a mistake that had been made and suffered through.

Trow writes about how in the America of his youth it was not acceptable for some people to be making $15 a week while others lived off the income of their income. Then he writes this:

About three years ago [mid-1990s] I noticed an extraordinary change in the Vanderbilt house ... The guides [rather than being in the spirit of a 1953 public librarian] were all young; not particularly well informed as to the overall flow of American history, but wildly well informed as to the history of the Vanderbilt family; and suddenly out of the woodwork, or out of some books, came all kinds of facts and figures about the Vanderbilts, in terms of how much money they had and how many houses and how many yachts and so forth, which showed that the Vanderbilts, at least in the minds of the guides, and I guess, probably, everyone else, had lately been put on a new kind of Mount Rushmore; these were people who had invented the aesthetic that everyone at this recent moment had decided to embrace. This, of course, represented a kind of defeat for FDR's intent. I didn't see one horrified face or one disapproving face as the young guides described plutocracy in its old form.

Well, Reagan did that, didn't he?

I'm reading and saying, Yes, yes, yes! It's particularly nice that Trow gets to Reagan because he tends to gloss over the Reagan years. The subtitle of the book is “Media Studies 1950-1998” but Trow rarely gets out of the 1950s, his formative years, and only sometimes into the 1960s, when he was at Harvard and then hired by The New Yorker, and also into the 1970s, when “Within the Context of No Context” was written. But here he finally lands on the 1980s: Reagan. The answer.

He adds, “But how on earth did it happen ...” I.e., how did Reagan do it? And he goes into the anti-money aesthetic of the 1960s left-wing, and how he, Trow, was at odds with that aesthetic. He recalls attending a 1969 meeting with a friend about turning Time magazine into a worker-owned publication like Le Monde, and how isolated he felt at that meeting. He liked the culture of the old artistocracy; he palled around with them, as we say today, and yet by 1998 he was against the newly sympathetic relationship to the old plutocracy in a way that his old left-wing friend was not.

He had gone from “Time magazine ought to be like Le Monde” to being at the party for the man who thought that Time-Warner ought to triple in size, perhaps.

Then he repeats his question about Reagan, “Reagan did it, but how did he do it?” and I'm thinking, C'mon. Tell us already! Because I know Trow. It won't be the typical answer. It won't be resentment against blacks (“Welfare queen,” etc.), and it won't be Carter's foreign policy (hostages, etc.), and it won't be Carter's domestic policy (“Are you better off ...” etc.). It won't be the radicalism of the left in the 1960s and the various humiliations America suffered in the 1970s, which is my vague answer. It'll be something better. Something right in front of our eyes.

But he keeps putting it off. He goes into a story about how Richard Avedon took a photograph of Diana Vreeland at the Reagan White House, curtsying before an amused Prince Charles, and how it's a real curtsy, and yadda yadda, and how one of the men in the background of this photo was Jerry Zipkin, whom he derisively calls a “walker,” which is a guy, probably gay, who takes society women around town. Zipkin was in Trow's social circle for a while and Trow didn't think much of him. And then out of the blue, when we're not looking, Trow suddenly gives us the answer:

And I looked at that photograph and I thought, “Oh, God, Studio 54.” And that's how Reagan did it.

Wait—WHAT? Studio 54?

So you read on. Trow writes about how the American aesthetic was often a New York aesthetic, since the center of television and publishing was in New York. Then he tells us a Studio 54 story, his Studio 54 story, how he went there with Diana Vreeland shortly after it opened, and how they sat in the VIP gallery and he looked out at a scrim celebrating cocaine use. Except he had a friend, a good friend, who was suffering from substance abuse at the time so Trow didn't think much of this celebration. Then he writes that Dionysian energy like Elvis' often gets warped by the media filter and how Studio 54 was the 1960s reconfigured as the 1970s; and then he writes this:

As of 1978, New York had run out of specific cultural information; Roosevelt had died and had been buried; Winchell could be Army Archerd from the Hollywood Reporter or any other angry tabloid person; there was no reason Walter Winchell, dancing on Roosevelt's grave, couldn't be that loathesome man who gave us Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. As to Hyde Park versus the Vanderbilt house, the Vanderbilts had won.

Right. But ... The connection? Between Studio 54 and Reagan?

You can guess, certainly. The VIP gallery stood for exclusivity rather than egalitarianism, as did Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, and suddenly that's what everyone wanted: the exclusivity of the rich and famous. With drugs. There's something to that. But just something. And it doesn't quite lead to Reagan.

For the final few pages of the book, Trow talks up the relationship between FDR and Walter Winchell, the fierce tabloid reporter, and how the Kennedys are the link between FDR and what we have now, “where political figures of every stripe and at every level struggle to find the next camera angle.” But Reagan? It has something to do with George Bernard Shaw's Heartbreak House, apparently, which Trow wants us to read, as well as preindustrial probity, which FDR embodied, and ... And then the book kind of swirls away and leaves you, or me anyway, bereft, without a final connection.

I mean, you go back and dig again. Right, so FDR is aristocratic but egalitarian, and Studio 54 is pedestrian but exclusive. It's undemocratic. FDR came from money but strove for egalitarianism, JFK added glamour, but in the 1960s we dipped our toe in greater egalitarianaism, greater democracy, and came out disgusted. We came out wanting the money and the glamour and the exclusivity. We wanted to be behind the VIP ropes.

But it's not enough. The point of the great thinker and the great writer, which Trow is, is to make the connections the rest of us miss; but Trow has a nasty habit, and this goes back to “Context” as well, of leading us to the Great Connection and then abandoning us there while he goes off on another tangent. He takes us halfway across the chasm and then helicopters out of there, toodle-oo, and we look to the other side, alone, without a guide, and we wonder, “But how do I make that leap?”

More, I'm sure, to come.

How did Reagan do it? Well ...

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)