Wednesday December 21, 2011

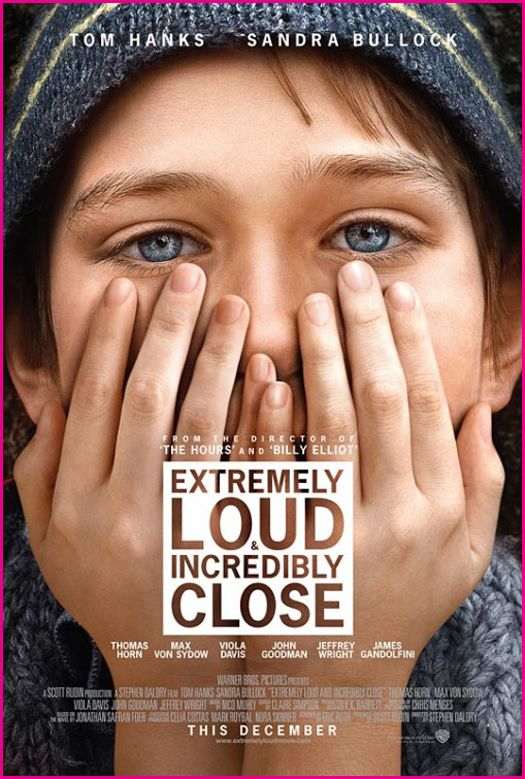

Movie Review: Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2011)

WARNING: EXTREMELY LONG AND INCREDIBLY FULL OF SPOILERS

Extremely loud and incredibly close describes most movies coming out of Hollywood but not “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close.” It’s called that, I assume, because that’s the way Oskar Schell (Thomas Horn), a 10-year-old with inconclusive Asperger’s syndrome, perceives the world. He’s frightened of its noises, frightened of its people, sees dangers everywhere. He’s a worst-case scenario guy—like me, I suppose—but 50 times worse. Walking on a dock: What if he falls through? Walking over a bridge: What if it falls down? Swinging on a swing: What if it breaks?

Of course, he, like most of us, never saw this one coming: What if a group of people purposefully fly airplanes into tall buildings and they come crashing down?

Oskar’s dad, Thomas Horn, Jr. (Tom Hanks), a jeweler, tries to focus his son’s mind by sending him on treasure hunts. He makes up stories. He tells him there was once a sixth borough of New York City but it floated away and the only evidence remaining is somewhere in Central Park—which, itself, was once part of that sixth borough until the people of New York, working together, dragged it to its current location. He’s an ideal dad who practices tae kwan do with Oskar, creates games like Oxymorons—in which the goal is to come up with more oxymorons than your opponent (“Original copy!”)—and encourages Oskar educationally, where he shines, and socially, where he doesn’t.

Unfortunately, on the morning of September 11, 2001, Thomas happens to have a business meeting on the 105th floor of the World Trade Center.

Unfortunately, on the morning of September 11, 2001, Thomas happens to have a business meeting on the 105th floor of the World Trade Center.

The movie opens to blue; then we see something flapping in front of it. A flag? No. Is that a shoe? Is it a body falling? Is it a body falling on the sky-blue day of September 11, 2001?

Yes.

Most of the action takes place a year later. In voiceover, which is used throughout, Oskar tells us that if the sun blew up we wouldn’t realize it for eight minutes because that’s how long it takes for light to travel to Earth. So for eight minutes, we’d still feel its warmth; we’d still see its light. And that’s how he feels about his father. And he fears that, after a year, his eight minutes are almost up. (This is a beautiful analogy, by the way.) So for the first time since that awful day, “The Worst Day” he always calls it, Oskar enters his father’s closet, which his mother (Sandra Bullock) hasn’t altered. He smells his sweater. He finds old film his grandfather took. And on a top shelf he spies his father’s camera, which, as he pulls it down, also pulls down a blue vase, which falls through the air and explodes on the floor. In it, he finds a small envelope, and inside the small envelope he finds a key. “Black” is written on the envelope. What could it mean? What could it open? What was his father trying to tell him? It’s the final treasure hunt.

After a neighborhood locksmith tells him that every key opens something, Oskar goes in search of that something. He figures “Black” is a name; and in the phone book he finds 472 Blacks, some of whom live together, and decides to ask each of them if they know anything about his father and/or the key. His phobias have intensified since 9/11—tall buildings, subways—so for the first Black on his list, Abby (Viola Davis), in Brooklyn, he steels himself, shakes his tambourine (which he uses to calm his nerves), and crosses the Brooklyn Bridge. She lives in a beautiful brownstone, where it appears to be moving day. She’s distracted, knows nothing about his father or the key, but he barges in anyway, asks for water, asks about an elephant postcard he finds in one of the moving boxes. Turns out she’s not the one who’s moving. A man, whose face we never see, is. It’s her husband and they’re separating. When she breaks down and cries, Oskar offers her this: “Only humans can cry tears, did you know that?” He tells her she’s beautiful. He asks, “Can I kiss you?” When she smiles and says it wouldn’t be appropriate, he asks to take her picture. At the last instant, she turns away, tears streaming down her cheeks. The Worst Day killed his father, which is why he’s there, but for her this is the worst day. What he’s doing feels awkward and awful. It almost feels like a home invasion.

More importantly, throughout, I couldn’t get past this thought: Why not phone?

Did I miss something? Are these the Blacks in the phone book without phone numbers? Did his father tell him to never use the phone in his treasure hunts? He certainly has a phone, and he’s an extremely logical kid, and he’s calculated that if he visits two Blacks every Saturday it’ll take him three years to complete his task, whereas, with the phone, he could finish it up in two afternoons, three tops. Instead, every Saturday, off he goes, meeting people and hearing their stories.

This is obviously the point. What matters is the face-to-face interaction. What matters is the journey. But the journey is so illogical, given the storyline, I couldn’t get past it. Oskar, with his Asperger’s mind, wants to think of every person, every “Black,” as a number in a gigantic equation, but after a time he realizes they’re closer to letters, and those letters spell a story, and those stories are messy. He wants a neat answer but everything just gets messier. That’s the point, too, but I still couldn’t get past the illogic. Dude, just pick up a phone.

After a time, Oskar is aided in his search by his grandmother’s renter (Max von Sydow), who showed up three weeks after 9/11, and who is obviously Oskar’s grandfather, Thomas, Sr. As a German teenager, he was caught in the firebombing of Dresden, which strangled all speech from him forever. He has YES and NO tattooed into the palm of each hand—like Robert Mitchum’s LOVE and HATE knuckles in “Night of the Hunter”—and writes everything else down. He also abandoned his family when Thomas, Jr. was young. He was a bad father. Now he’s trying to be a good grandfather.

It’s a relief when he joins the search. It’s tough to occupy the stage alone, and it’s particularly tough for a 10-year-old; and while Thomas Horn does an amazing job for someone who’s never really acted before, who came to fame winning $31,000 on “Teen Jeopardy,” his character, Oskar, is often too precocious to be believed and too annoying to be liked. Kids are often bratty, and Asperger’s kids have their own brand, but there was a tinny quality to Oskar’s flame-outs. When, in voiceover, he lists off all the things that make him panicky, in an increasingly panicky voice, it just doesn’t work. When he tries to tell his story to his grandfather, his secret story, the one he’s been keeping from us about the answering machine and the six voice messages his father left on 9/11, he gets extremely loud and panicky about it. That, too, feels off.

Eventually, when Thomas, Sr. senses he’s hurting Oskar more than helping him, he abandons the search, and the grandson, as he abandoned the son, but Oskar keeps going. And eventually he finds the answer to the mystery of the key. It’s a good answer because it’s not Oskar’s answer. It doesn’t satisfy him but it satisfies us—in part because we get to watch Jeffrey Wright, the most underutilized great actor in Hollywood, act for a few minutes.

As for the horror of the sixth answering-machine message? It’s both less and more horrifying than we imagined. In content, it’s simply Thomas, Jr., calling again, knowing he’s about to die, and repeating, over and over again, to his son, whom he’d hoped to talk with, “Are you there? ... Are you there? ... Are you there?” It’s a kind of echo, repeated so often, but it also echoes back throughout the movie, since that’s what the son is now doing. Oskar’s search is his own query, his own “Are you there?” to his father.

Why is this horrifying? Because Oskar was there, in the room, listening to his father leave this message, but too panic-stricken to pick up. He asks forgiveness of the adult to whom he confides the story, and of course it’s granted, and Oskar feels relief—it’s a helluva thing for a 10-year-old boy to be carrying around—but afterwards the movie forgets it and I couldn’t. I thought: That’s going to weigh on Oskar more as he ages. He’s going to realize that in his father’s last moments he could have spared him some anguish, could have been that voice, the last voice he communicated with, before he went into the abyss. But he couldn’t and didn’t. It’s not a matter of the need for forgiveness; it’s a matter of overwhelming sorrow that will never end.

“Extremely Loud” is supposed to be a tearjerker so I was surprised it didn’t jerk more tears out of me. It took about 50 minutes, and Sandra Bullock’s “It doesn’t make sense” speech, before I teared up. The second time was during her flashback to 9/11. I guess it was mostly Sandy who made me cry. She’s also the tidiest aspect of the untidy end. Where was the mother during all this? How could she let her son traipse around New York, going into strange homes, in a fruitless search? Isn’t she smarter, more caring, than that? Yes. Yes, she is.

A lot of talent went into this. It was written by Eric Roth (“Forrest Gump,” “The Insider,” “Munich”), directed by Stephen Daldry (“The Reader,” “The Hours”), and adapted from a novel by Jonathan Safran Foer (“Everything Is Illuminated”). Both Hanks and Bullock nail it. The kid mostly works. I never tire of Max Van Sydow or Jeffrey Wright. It’s about the aftermath of an event none of us will ever forget. Yet it doesn’t quite coalesce. The mother’s 11-hour revelation retroactively covers up some of the false notes, but not all of them, and a tinny taste lingers. The movie wants us to believe in something, in all of us messy, multihued people, with all of our sad stories, making our way in the world. It wants to say that we all care about each other. But the world doesn’t care this much. It doesn’t have this much patience with us, no matter how much prep work goes into it. It’s more cruel than this. A warning should be flashed at the start of the film: Kids, don’t try this at home.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)