Friday April 22, 2011

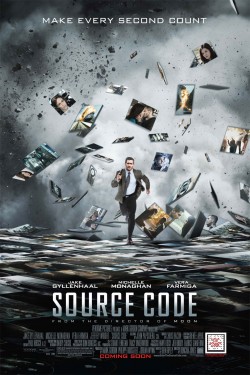

Movie Review: Source Code (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The real tension in “Source Code” isn’t whether Capt. Colter Stevens (Jake Gyllenhaal) will be able to find the bomb aboard the commuter train heading to Chicago that kills 200 people on a beautiful spring morning, nor whether he can find the bomber, or bombers, so a dirty bomb won’t obliterate 2 million people in downtown Chicago later that day. No, the real tension, halfway through the movie, is this: How are they going to give us a happy ending?

We know, by this point, that the latter bomb probably won’t go off (Hollywood won’t allow it post-9/11), but we also know that the former bomb has already gone off. That reality can’t be changed. Capt. Colter? He dead. The girl he likes? She dead. So if both leading man and leading lady are dead, how do we get the happy ending requisite of modern Hollywood movies?

I’ll start at the beginning. (It’s a good place to start.)

I’ll start at the beginning. (It’s a good place to start.)

Stevens is an Air Force pilot stationed in Afghanistan who wakes up one day on a commuter train heading to downtown Chicago, opposite a pretty girl, Christina Warren (Michelle Monaghan), who calls him Sean, and tells him, “I took your advice. It was good advice. Thank you.”

A soda pop can is opened, a woman spills coffee on his shoe, the train conductor asks for his ticket, which, despite his protests, is in his breastpocket. He’s freaking. He feels sick. With the train in the station, he stumbles through the car, past a gold watch salesman and a guy in a letter jacket who finished third in some “American Idol” for standup comedians, and goes out on the platform for a breath of fresh air, where a red-haired cyclist returns a dropped wallet to a departing passenger. Stevens asked the cyclist, who is also departing the train, the name of the city in the distance. “Chicago,” the kid says with a bemused look. Back on the train, the pretty girl, Christina, treats Colter’s pain, his identity crisis, as a joke, and he retreats into the bathroom and splashes water on his face ... which isn’t his face. He checks his wallet. It’s the wallet of Sean Fentress, teacher, the face he sees in the mirror. Now he’s freaking even more. Outside the bathroom, Christina consoles him. “Everything’s going to be okay,” she says. At which point the entire train, and all the people in it, blows up.

Nice open.

At this point, Stevens is transported into a stark, gray pod chamber, strapped to a chair, where he communicates, via video screen, with U.S. Air Force Officer Colleen Goodwin (Vera Farmiga), who tries to acclimate him to his surroundings and assignment. He says he’s in Afghanistan. No, she says, he’s on another mission. He asks her about the simulation he’s going through. No, she says, it’s not a simulation. A figure, a man with a cane, sometimes shows up on the video screen, annoyed, uncommunicative, presses some buttons, leaves. His name is Dr. Rutledge (Jeffrey Wright). He exudes a scientific distance and fussiness. “Find the bomb,” Goodwin tells Stevens, “and you’ll find the bomber.” Then she sends him back to the train and we get “I took your advice” and the coffee spill and the ticket punching all over again.

Basically the movie is part “Inception” and “Groundhog Day,” with some “Speed” tossed in.

So if Stevens isn’t experiencing a simulation, what is he experiencing? Rutledge, when forced to communicate, uses the not-bad metaphor of a light bulb: How it continues to glow after it’s been turned off. The mind is like that, he says. It continues to work for approximately eight minutes after you die. So Stevens is inhabiting the last eight minutes of Sean’s existence, with whom he was a good synaptic match. Except he’s not doing the things Sean did. He has free will. In this manner, the third time on the train, he finds the bomb, in an air duct in the bathroom, and by the fourth time in he’s scoping out potential bombers. Because that bomber will strike again, and soon.

But where is Stevens all the while? Whenever he asks, Rutledge appears annoyed and Goodwin betrays a touch of sadness. So on the train, while he’s scoping out other information, he asks Christina to find out about his friend, Capt. Colter Stevens, stationed in Afghanistan, who went missing two months earlier. She checks via smartphone and returns betraying a touch of sadness herself. “Your friend is dead,” she tells him. “He was killed in action two months ago.” For a second, before the train blows up yet again, reality becomes distorted, like a TV signal breaking up, and Colter remembers, in flashes, the helicopter crash. Back in the pod, he seeks answers. “Goodwin,” he says. “One soldier to another: Am I dead?” Goodwin, apparently disobeying orders, owns up. “Part of your brain remains activated,” she says. The capsule he’s in is itself a manifestation, and, with knowledge, it begins to break apart, and Colter, like in a nightmare, seems to get smaller and smaller.

The movie makes an interesting decision at this point. Colter suddenly refuses to cooperate. Time in the real world is running out, and yet for several trips back to the train he does nothing, finds nothing, decides that being used in this fashion when he’s all-but-dead (“You are a hand on a clock,” Rutledge tells him without sympathy; “we set you and we re-set you”) frees him from following orders or caring about the two million in downtown Chicago. I’m not sure if this is a bold decision or a miscalculation. The conventional wisdom is that, in drama, one life means more than two million—we care about Colter, whom we know, but not the two million, who are just a number—but I’m not sure, in a post-9/11 world, that that’s true anymore. The “terror” in “terrorism” is always its randomness, the thought that “It could’ve been me.” In this manner we do care about the two million. They could be us. And why doesn’t Colter care about us? I thought he was the hero.

Either way, it’s a blip. Rutledge plays him an audio recording of his father—with whom he had issues, with whom he wished he could’ve had a better, final conversation—speaking at the funeral about his son’s bravery and self-sacrifice, and his face hardens. “Send me back in,” he says.

This time he figures it out. In past iterations he suspected a Muslim-looking businessman and a student with a laptop, but the bomber turns out to be the very bland-looking dude who drops his wallet. The dude actually does it on purpose. He wants it on the train as evidence that he died on that train. (Although: won’t the wallet be ash after the explosion?) He’s also got a bigger, dirtier-looking bomb in a white van in the parking lot inside a container painted with stars and stripes. Those stars and stripes, and an earlier reference to “racial profiling,” is as political as the movie gets. The terrorist isn’t the worst of them, he’s the worst of us, but, when explaining his motivations he doesn’t sound like the worst of us; he sounds as bland as he looks. He’s destroying Chicago because “the world is hell but we have the chance to start over in the rubble.” That’s it? Seriously?

This iteration ends with the home-grown terrorist getting away in the white van and both Colter and Christina shot and dying in the parking lot (“Everything’s going to be okay,” he tells her, rather than she him); but Colter now has the evidence, which, back in the pod, he relays to Goodwin and Rutledge and the bomber is stopped before detonating the dirty bomb.

Happy ending? Not really. Sure, downtown Chicago is saved and all, but Rutledge, the jerk, is feted, while Colter, our true soldier, is still a fragment of a man, whose memory is to be wiped clean and used again and again in similar circumstances, while Christina, the pretty girl, with whom he’s gotten close lo these many iterations, is dead on the train. Nothing can be done to change that.

Except.

There’s always an “except,” isn’t there? Why not? If you can keep the brain of a dead soldier alive in perpetuity, then transport his mind into the body of a dead train passenger, who’s in the past, and keep doing it until it’s done right, well, who’s to say what you can’t do?

That’s the thing. The technology to do all this is so astounding it’s as if Rutledge is God. Yet the film treats him as he treats Stevens: as a nuisance. He’s a jerk, egotistical, working to do what? Save two million people? With his brain? Big deal. What about the cute boy and girl? Do they get together?

In this regard, Colter has a plan. He asks Goodwin to send him back one more time for those eight minutes on the train. And this time he does everything right. He stops the bombs, gets the gun, handcuffs the terrorist to the train, and bets all of his money, $126, that the comedian can’t make everyone in the compartment laugh. Then he kisses the girl. That’s where this iteration ends. As the eight minutes elapse, Goodwin, as per his request, pulls the plug on Colter and lets him die, and we get a moment frozen in time: with everyone laughing; with boy kissing girl.

Oh, I thought. That’s actually … kind of beautiful.

Unfortunately the moment doesn’t stay frozen for long. Colter’s actions—along with Goodwin pulling the plug?—have created ... wait for it ... an alternative reality, in which everyone lives, and in which Dr. Rutledge and Goodwin aren’t even called upon to begin their project with the remains of Capt. Stevens because the train never blows up. Instead it pulls safely into the station on a beautiful spring morning, and boy and girl, Christina and Sean/Colter, look at their reflection in the Bean, that great steel legume in Millennium Park in the Loop district of Chicago, and life and love is new. The End.

Crap, I thought.

Now we have nothing but questions. So if everyone survives … what happens to Sean? His body is still inhabited by Colter. How does that work exactly? Has he just been stomped out of existence? And how will Colter live life as Sean? Sean’s a teacher. Will Colter be able to do that? Teach that? My god, he won’t be able to recognize his mother, father, friends and family. No one. He’s all alone, really. He just knows Christina. Poor Christina. She thinks she’s got a new boyfriend, someone to have coffee with, but she’s really got a man, in the body of another man, who knows no one but her, who will be forced to cling to her for every second of every day. That relationship’s a disaster in the making.

Wait! Doesn’t Colter now exist twice in the same reality? He’s in Sean’s body, hanging out by the Bean, and in his own mangled body, on life support in that pod chamber. And what happens when Rutledge activates him? Will Sean return? Or is he already there—helpless inside his own body? We think Colter’s the hero but maybe he’s really a greedy bastard taking over as many lives as possible. Maybe someone you know. Maybe yours.

And “Source Code” as a title? Could we please please try to be a little more specific rather than so blandly generic?

I still enjoyed myself. I should mention that. The story zipped, Gyllenhaal is good, I fell in love with Michelle Monaghan all over again. I just wished they’d stopped at that frozen moment. I think people wouldn’t mind a bittersweet ending rather than another Hollywood ending. I think we’re getting tired of this shit.

Colter: Expect to see this look more often as you fumble through Sean's existence.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)