Tuesday March 26, 2024

Rise vs. Surprise: What's Good for Baseball?

Joe Posnanski is in the midst of counting down all the MLB teams from worst (Rockies, right? Right) to best (Braves, probably), and today he landed on No. 14, the Arizona Diamondbacks. With each team, he starts out with an anything topic that's usually fun and fun to read before getting to the nitty-gritty: who's good, who might be good, what's working and what isn't. The anything topic is just where his mind goes with that particular team, and today it went to: Were the D-Backs the most suprising team this century to win the pennant? No other pennant winner this century has had a negative run differential, for example, so they're certainly in the running. Last season, they eked into the post, had a good run—through Brewers, Dodgers and Phillies—and made it to the Series. Pos then goes into our two baseball seasons: the long, 162-game one, where the best teams rise, and the short sprints of October, where teams like the D-Backs can surprise.

And he asks: Is this good for baseball?

He asks because he doesn't think it is. Those two types of seasons are fine for other sports, but other sports always get to play their best players (unless injured), and that's not baseball, certainly not with pitchers. He writes:

If you're going to make baseball a playoff sport, then do it—140-game season, eight playoff teams in each league, 15 seven-game series filling September and October, just go all in. This will allow more teams to try and have Diamondback-like runs to glory.

And if you want to keep the 162-game season at the center of the sport, and better reward the teams that play well throughout, then scale back the playoffs to four teams in each league and have them play a seven-game series in October.

I'm with Joe on this, but I think the current Lords won't cut back on either revenue stream (reg. season or playoffs), and so won't fix the problem.

Monday March 25, 2024

Movie Review: Dune: Part Two (2024)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Is Dune the text at the fulcrum of popular culture? Feels like it. It’s the midpoint of the journey of our heroic journeys.

Which go something like this.

In David Lean’s 1962 Oscar-winning film, “Lawrence of Arabia,” a blue-eyed member of the elite goes native in a desert community and prospers; he winds up attacking his own empire and is exalted by the desert people. They chant his name.

Three years later, Frank Herbert published his novel, “Dune,” in which a member of the elite goes native and blue-eyed on a desert planet. He learns mind-control and the desert people exalt him as the long-lost messiah. They chant his name. He is deemed The One as he takes on the Empire—only to realize that he is related to his enemies.

Twelve years after that, in George Lucas’ “Star Wars,” a boy on a desert planet learns mind-control in order to take on the Empire—only to realize, mid-journey, that he is related to his enemies.

Denis Villeneuve’s “Dune” movies really underline how much Herbert’s story owes to T.E. Lawrence, and how much “Star Wars” borrows from it. But the journey of our heroic journeys feels less than heroic to me. Once upon a time, our stories were grown-up and historical, rooted in life on Earth; then they gave way to childhood fantasy.

But these are good movies. This is arthouse “Star Wars.”

How do you like your blue-eyed boy, Mr. Death?

My favorite moment of revenge, by the way, didn’t have anything to do with the demise of Baron Harkonnen (though the insects on his corpse were a nice touch), nor making Christopher Walken’s Emperor bow and literally kiss the ring (because, like in “Star Wars,” the Emperor was unseen in the first film and a last-minute addition to the second). No, it was when Paul used THE VOICE against the all-powerful and shrouded Rev. Mother Mohiam (Charlotte Rampling), the seer who orchestrated most of the tragedy we’ve been watching for the past three years:

My favorite moment of revenge, by the way, didn’t have anything to do with the demise of Baron Harkonnen (though the insects on his corpse were a nice touch), nor making Christopher Walken’s Emperor bow and literally kiss the ring (because, like in “Star Wars,” the Emperor was unseen in the first film and a last-minute addition to the second). No, it was when Paul used THE VOICE against the all-powerful and shrouded Rev. Mother Mohiam (Charlotte Rampling), the seer who orchestrated most of the tragedy we’ve been watching for the past three years:

Rev. Mother: Consider what you are about to do, Paul Atreides …

Paul: SILENCE!

[The force of the voice knocks down the Reverend Mother]

Rev. Mother: [fearfully] Abomination.

God, that was great. And maybe my reaction is indicative of the true power in this universe. It’s not with this bloated man, nor that decrepit old one, nor the young, bald psychopath. It’s with the women. The seers. The Bene Gesserit. And now a man has joined them.

“Dune: Part Two” totally worked. It’s a great story, the visuals are amazing, and while it’s long (nearly three hours) I felt like it wasn’t long enough. I felt like, to truly tell this story, you need a miniseries. Maybe we’ll get that someday. Though I do recommend watching the first movie again before you see this. Unless, of course, you already know the story. I just know it helped me.

Hell, even with rewatching it, I missed the part where Gurney Halleck (Josh Brolin) survived. I thought he bit it along with Leto (Oscar Isaacs) and Duncan Idaho (Jason Momoa).

So, in our last episode, the Atreideses were assigned by the Emperor to replace the Harkonnens as fiefholders on the desert planet of Arrakis, the source of “spice,” a psychotropic substance that also allows for interstellar travel. It’s as if LSD also powered automobiles, I guess. But it was less promotion than set-up. The Emperor feared Leto’s growing power and wanted him eliminated. The Harkonnens do just that. But Paul Atreides (Timothy Chalamet) and his Bene Gesserit mother, Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), escape into the desert.

There, they meet, and are almost killed by, the native Fremen peoples, who know how to fight and survive in the desert. Jamis, the warrior, challenges Paul, Paul wins. That’s where we left off.

Now they’re going native. And as Paul goes through various rituals and adopts the name “Muad’Dib” (Desert Mouse), and his eyes keep getting bluer from the spice and he keeps outfoxing Baron Harkonnen’s inept nephew (Dave Bautista), we periodically cut to other planets, where we see:

- Baron Harkonnen plotting ponderously amid the mudbaths designed to excrete the poison inhaled in the last movie

- Princess Irulan (Florence Pugh) journaling, and realizing that Paul Atreides may be alive, and that her father, the Emperor, caused the whole fiasco

- The rise of the youngest Harkonnen nephew, Feyd-Rautha (Austin Butler), who is pale, hairless, brutish and insane

Lady Jessica also goes through rituals, drinking yadda yadda, and oh no, she shouldn’t have done that when she was pregnant! But whatevs.

Increasingly, and via Fremen leader Stilgar (Javier Bardem), amusingly, or maybe heartwarmingly, the natives think Paul is the return of the Messiah. This is particularly true in the south, which is why Paul doesn’t want to go there. Lady Jessica does. She figures, hey, nothing safer than being considered the Messiah. But Paul is disturbed by visions: millions dying in his father’s name. He doesn’t want that. Or that Paul doesn’t want that.

I’d forgotten he gets corrupted. Is that why I never finished the trilogy? The hero stopped being the hero? Watching this, I was also disappointed when Paul reunites with Gurney Halleck. I liked him alone with the Fremen.

Eventually, though, he’s forced to flee south, where for some reason he drinks the Water of Life, goes into coma, comes out of it, and now he’s less Paul than he was before. He can see the future clearer and he believes in the prophecies more. Or does he merely use them? I’m unclear. How much is calculated and how much is he buying into everything? Or maybe he should be buying into it all, since he is what he is.

Anyway, massive forces move against each other, Paul and the Fremen overwhelm the Harkonnens and retake the planet, and Paul kills the Baron. Then he agrees to fight Feyd-Rautha, who, I don’t think, the movie played up enough. His one big battle before Paul is with three creatures in an arena, but the decks are stacked—two of them are drugged. He seems less menacing than pampered. Or he’s menacing for being pampered. Either way, he proves a tougher battle for Paul than anyone else in these movies. But he loses.

A lot of what happens in the last hour I was confused by. Why does he demand Princess Irulan’s hand in marriage? To unite families? He’s already defeated her family. Is he trying to avoid the holy wars he sees in his visions or doesn’t he care about that anymore? Maybe he’s a big fan of journaling.

Books of Thomas, Paul, Luke

I shouldn’t make fun. I liked it. I particularly liked Javier Bardem’s Stilgar: the crumbling of his curmudgeonly nobility as more and more he wants to believe. Chalamet is great, too, in a tough role for such a skinny malink. Zendaya works as Chandi, the Fremen guide and love interest. Lea Seydoux is in this too? What a cast. Anya Taylor-Joy even shows up in a vision as Paul’s grownup sister. Yes, like Luke, Paul has a sister. Maybe this one will prove more useful. (Sorry, Leia fans.)

I’m interested in seeing where this goes. Maybe it goes to places the “Star Wars” movies should have but didn’t. And I’m curious how this, the outsider in the desert, the T.E. Lawrence story with superpowers, became the heroic journey of all of our voyeuristic lives. Not enough has been written about that.

Sunday March 24, 2024

The First Trump Lie in the NY Times Appeared in 1973

The first time Donald Trump's name appeared in The New York Times, back in 1973, in an article about his father entitled “A Builder Looks Back—and Forward,” it was accompanied by a lie:

The Donald graduated first in his class at Wharton? Impressive!

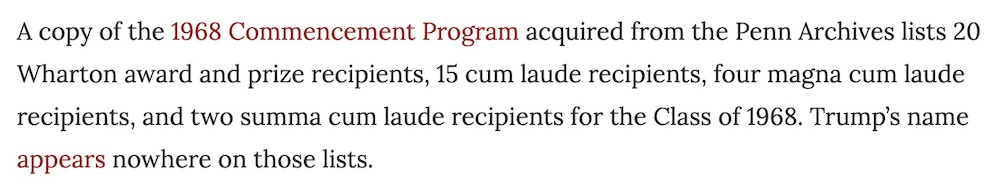

Yeah, no. From The Daily Pennsylvanian, a student newspaper, in 2019, in article entitled: “Mary Trump says 1968 Wharton graduate Donald Trump cheated on SAT to get into Penn”:

The Times still hasn't corrected their 1973 story. But don't worry: There's way more where that came from.

Saturday March 23, 2024

Movie Review: The Maltese Falcon (1931)

WARNING: SPOILERS

There’s a surreal quality to watching the original 1931 version of “The Maltese Falcon.” It’s like explaining a dream to a friend: You were you, but not really you. Here, Sam Spade is Sam Spade, but not really Humphrey Bogart.

Actually, not at all Humphrey Bogart.

All his teeth

He’s Ricardo Cortez (nee Jacob Krantz), a wannabe Valentino by way of Zeppo Marx, and his Sam Spade isn’t exactly the cool, professional hero of John Huston’s 1941 classic. He’s a lothario—leering at the pre-code women with all his teeth.

He’s Ricardo Cortez (nee Jacob Krantz), a wannabe Valentino by way of Zeppo Marx, and his Sam Spade isn’t exactly the cool, professional hero of John Huston’s 1941 classic. He’s a lothario—leering at the pre-code women with all his teeth.

At his office he kisses goodbye to a midday tryst (legs only) before nuzzling the neck of his semi-resistant secretary, Effie (Una Merkel), who then ushers in the movie’s femme fatale, Ruth Wonderly (Bebe Daniels), with the familiar line, “You’ll see her anyway—she’s a knockout.” In the midst of this he gets a call from Iva Archer (Thelma Todd of Marx Bros.’s fame), the pain-in-the-neck wife of his partner Miles Archer (Walter Long), and yes he’s banging Iva, too.

All of which makes us aware of the great lie in the ’41 version: Sam Spade is a skunk. Sure, no midday tryst, and he and Effie banter like pals, but he is banging his partner’s wife. That shit ain’t cool. But Bogie gets away with it because, well, he’s cool. He doesn’t leer at anyone or nuzzle anyone’s neck; he’s a professional throughout. Plus he’s friends with everyone in town: this cop, that cab driver, the other hotel dick. It’s the ’41 Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan) who acts the skunk—checking out Ruth Wonderly and all but going hubba hubba. “You’ve got brains—yes, you have,” Spade tells him sardonically, and next thing you know Archer is killed in cold blood and no one cares. He had $10k in insurance, Spade says, no children, and a wife that didn’t like him. Plus, we could add, a partner who couldn’t wait for the body to get cold before taking his name off the door.

The ’31 version of Archer is way more sympathetic. True, he’s got a face like a Mack truck, but when he overhears his wife confessing her love to his partner we feel his pain. Once Ruth leaves, we figure he’s going to wipe the floor with Sam. Instead:

Archer: Any phone calls for me, Sam?

Spade: Ohhhh, yes. Your wife called.

Archer: Yeah? What did she have to say?

Spade: Ohhhh, wanted to know when you were coming home. And she said she missed ya an awful lot!

Is that an unintended irony of the Production Code? When you sweep sex under the rug, you lose accountability. You lose morality. You kind of make it OK to covet thy neighbor’s wife. Way to go, Catholics.

Here, Archer’s body is found in a back alley near a chop suey joint—rather than down a construction site—but like with Bogart’s version Sam has no time to check on it. Unlike in the Bogart version, he stops and exchanges a few words of Cantonese with the owner of the chop suey joint, Lee Fu Gow. This is crucial info, it turns out. Spade now knows (even if we don’t) that Archer was killed by a woman. None of this was in the Huston version, by the way, because none of it was in the Dashiell Hammett novel. You can thank the ’31 screenwriters: Maude Fulton (“Other Men’s Women”), Brown Holmes (“I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang”) and an uncredited Lucien Hubbard (“Smart Money”).

There’s a lot of such little differences between films. We get no opening title cards about the Knight Templars of Malta and Charles V of Spain, we don’t see Archer being killed, there’s no shaking Wilmer's tail or booting him from the lobby of the Hotel Belvedere. Wilmer doesn’t even show up until the big meeting with Casper Gutman, and that meeting is a one-fer. Gutman begins it, then Joel Cairo shows up in the next room, returning to the fold, as it were, with intel that the black bird is arriving on the ship La Paloma, docking that day. So we better understand why Gutman slips Spade a mickey—he doesn’t need him anymore. What we don’t get is why Joel Cairo bothers to return to the fold. If he has the intel, why share it with the Fat Man?

Overall, there’s less playfulness with Cairo. Or the playfulness is Effie’s rather than the movie’s. She tells Sam he has a gorgeous new customer, and as Sam gets ready to sink his teeth in, in walks Joel Cairo (Otto Matieson). There’s no “Gardenia,” no lilt to the soundtrack, no supposition that he’s gay; and after Sam knocks him out there’s barely anything in his pockets. Just the wallet. Lorre has the wallet, three passports, foreign coin, a ticket to the Geary Theater and a scented handkerchief. (Cue lilt again.) He has a storyline in his pockets. He has a life. Plus he’s played by Peter Lorre. (No offense to Matieson, a Dane who played Napoleon Bonaparte several times in the silents.) Gutman, meanwhile, is played quite sweatily by Dudley Digges, who is memorable as the evil “boys prison” warden in “The Mayor of Hell.” Wilmer? That’s Dwight Frye, the original Renfield in Universal horror flicks, as well as Dr. Frankenstein’s assistant (Fritz/Karl) in the first Frankenstein films. They’re no slouches, in other words. They're also not Lorre, Sidney Greenstreet and Elisha Cook, Jr. Not close.

One improvement? While Mary Astor is great at playing a school-marmish type who can suddenly get into a catfight with Lorre’s Joel Cairo, I have trouble seeing Bogart’s Spade losing his heart to her. She’s not the “knockout” she’s made out to be. Bebe Daniels is closer to that, and Cortez’s Spade doesn’t really fall for her that hard. It’s more lust than love. Daniels, who played the star who has to break her ankle so Ruby Keeler can rise in “42nd Street,” was 30 years old at the time, but had been acting in movies for more than 20 years. In 1910, in just her second movie, she played Dorothy Gale in a short version of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” One wonders if she was destined to play roles that, in later, better productions, would be made more famous by someone else.

Repping SF

And the hits keep coming—if slightly off-key:

- “We didn’t believe you, we believed your $200.”

- “You’re pretty good. As a matter of fact, you’re very good. It’s chiefly your eyes, I think, and the throb you get in your voice when you say, ‘Oh, be generous, Mr. Spade.’”

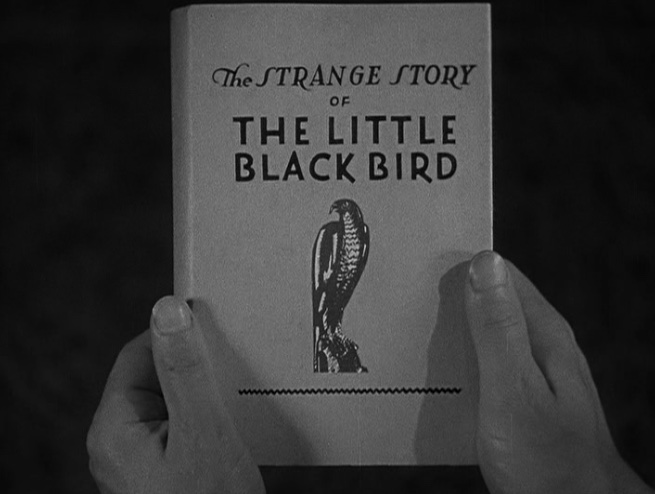

- “A statuette. The black figure of a ... bird.”

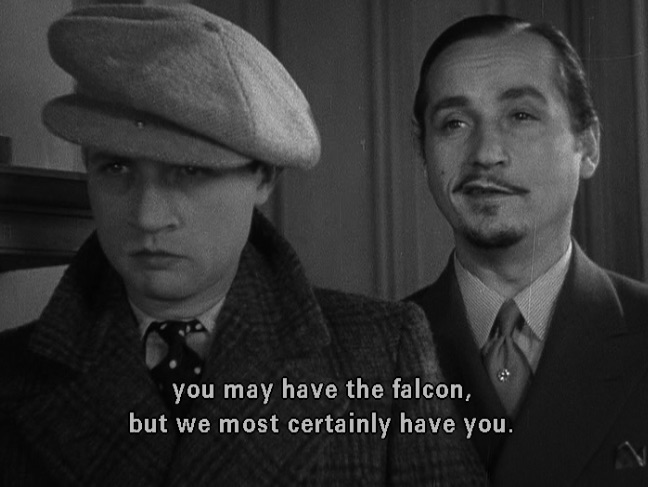

- “Permit me to remind you, Mr. Spade, you may have the falcon, but we most certainly have you.”

- “Why, I feel toward Wilmer exactly as if he were my own son.”

- “You palmed it, Gutman. ... I said you palmed it.”

Each line is great, but you miss Greenstreet’s harrumph, Lorre’s whine, Bogart’s cool.

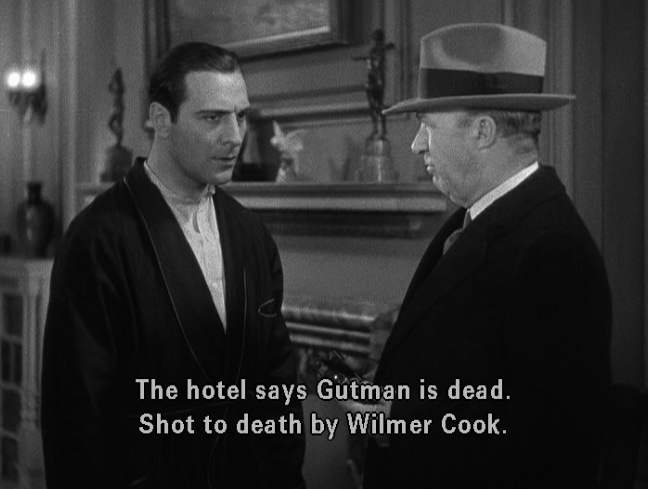

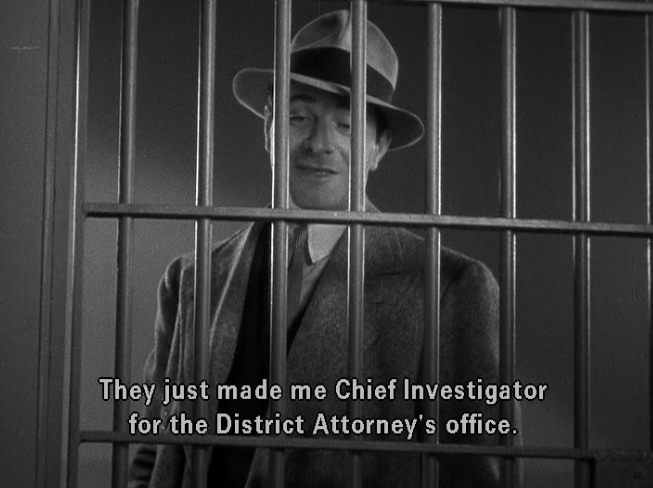

The ’31 version is directed by Roy Del Ruth, who directed some good early Cagneys (“Blonde Crazy,” “Taxi!”) and crappy later ones (“West Point Story,” “Starlift”), and it’s still early in the sound era so the camera doesn’t do much. Everything feels two dimensional. It’s straight-on shots, often with just one person in the camera frame. There’s no sense of humor to the movie, and no sense of tragedy. When the Falcon is finally uncovered, there’s nothing monumental about it. You don’t lean in the way you do in the Huston version. And that great ending, where the elevator gate clangs shut on Mary Astor like the bars of a jail cell, and then descends as if into hell while the soundtrack pounds, well, there’s nothing close to that here. Huston ended it like the best of Hitchcock—ripping the Band-Aid off—while this one just keeps going. Spade, now the chief investigator for the DA’s office, visits a disheveled Ruth/Brigette in her cell, and she tries to coax some of her moxie back. No go. Afterwards, he privately tells the female guard to give her everything she wants. When the guard asks where to send the bill, his mood becomes oddly buoyant: “The district attorney’s office!” he practically shouts. Not exactly “The stuff dreams are made of.”

Oh, another difference? How they open the film. How do you let viewers know we're in San Francisco? Huston opens with a nice shot of the Golden Gate Bridge. Of course. They don't do that here or the simple reason the Golden Gate Bridge didn’t exist in 1931. They began building it in ’33 and it opened to traffic in ’37. So what repped San Francisco in 1931? The Ferry Building.

SLIDESHOW

Friday March 22, 2024

Poking Holes in Potatoes

Voting rights attorney Marc Elias recently posted an excerpt from a 2022 New Yorker profile of him on social media. Worth reading the excerpt:

One evening, when I was talking to Elias, trying to glean what he does when he isn't working—nothing, apparently, except play with his four dogs (Frost told me that Elias “probably needs more hobbies”)—he told me a story. It was about a man whom Elias met around the time of his bar mitzvah. “This guy, an American prisoner of war, who was Jewish, in Nazi Germany, was put in a work camp where he had to pick potatoes,” Elias said. “He and the other men would take little pieces of barbed wire from the fence, and stick holes in the potatoes” to make them more perishable. “Just imagine an undernourished prisoner of war, in a thin uniform, with no gloves, in the winter, taking barbed wire in his bare hands and poking holes so the potatoes would rot and the German Army would not have fresh potatoes.”

This is what Elias recalls when people say that his litigation won't make a difference, or that he's bringing too many cases during a time when the courts lean overwhelmingly conservative. “I'm still going to try,” Elias continued. “It may not work. But I'm going to poke holes in the potatoes for as long as I have to, until democracy is either safe or I no longer can serve any useful purpose.”

Worth reading the whole profile, entitled “The First Defense Against Trump's Assault on Democracy,” by Sue Halpern.

BTW, I can't imagine meeting or knowing Elias and your reaction to his work—to his face!—is “It won't make a difference,” rather than shame that you yourself are not doing more.

Thursday March 21, 2024

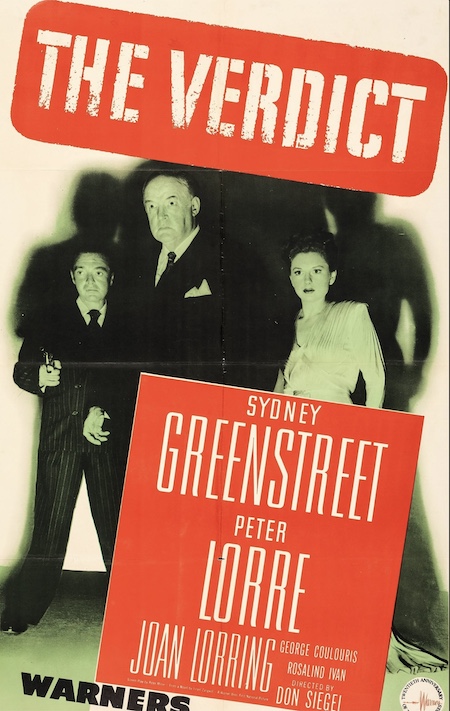

Movie Review: The Verdict (1946)

Number nine... number nine... number nine...

WARNING: SPOILERS

This is the ninth and final film Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre appeared in together. Chronologically:

- The Maltese Falcon (1941)

- Casablanca (1942)

Helluva one-two punch. Warner Bros. probably thought “Hey, why not put them in a movie with George Raft? He’s another Bogart, isn’t he?”

- Background to Danger (1943)

OK, so back to Bogie.

- Passage to Marseille (1944)

Wait, what if we made them the stars?

- The Mask of Dimitrios (1944)

Or remade “Casablanca,” kinda, with Paul Henreid reprising, and Hedy Lamarr in the Ingrid Bergman role?

- The Conspirators (1944)

And then the rest:

- Hollywood Canteen (1944)

- Three Strangers (1946)

- The Verdict (1946)

Nine movies in five years. If that seems like a lot, consider that Greenstreet appeared in only 24 films and all of them within one calendar decade: from “Maltese Falcon” in 1941 to “Malaya” in 1949. He died in 1954.

Puffy and wan

I wish “Verdict” were better but at least it’s not bad. Greenstreet is well-cast as an 1890s Scotland Yard superintendent, while Lorre is miscast as a devil-may-care artiste and libertine. That role has Claude Rains written all over it.

I wish “Verdict” were better but at least it’s not bad. Greenstreet is well-cast as an 1890s Scotland Yard superintendent, while Lorre is miscast as a devil-may-care artiste and libertine. That role has Claude Rains written all over it.

The movie exudes its Britishness so much that it feels a bit like a Gaumont production. Nope. Filmed on the Warner Bros. lot by montage director Don Siegel, given his first helming gig, with perpetual fog, close streets, top hats, overcoats and London cabs, along with Cockney 101: “I (fill in the blank), I did.”

It opens with an execution at Newgate Prison, congratulations from a constable to Supt. Grodman (Greenstreet), followed by Grodman’s lament that artists create symphonies and paintings while he, if he does his job well, merely creates death. Then he goes to Scotland Yard and discovers the man they’d just hanged was innocent. He’d claimed his alibi was in Wales, but they’d never found him. Because he’d gone to New South Wales—in Australia. For some reason, Grodman becomes the scapegoat for all this, he’s asked to resign, and the opportunistic John R. Buckley (George Coulouris), all but paddling his fingertips together, takes his place.

And with what great underlying contempt Greenstreet annunciates “Buckley” for the rest of the film.

Initially stunned at being let go, Grodman pivots to writing a memoir of his 30 years of policing, which might prove a manual for new Yard recruits, with illustrations by his artist friend Victor Emmric (Lorre). One evening, the two are drinking with Arthur Kendall (Morton Lowry), the nephew of the wrongfully executed man, when Clive Russell (Paul Cavanaugh) shows up. Russell is an MP working with the miners of Brockton—one assumes he leans left—and Kendall despises his politics. And vice versa. Outside, Russell threatens Kendall. Then showgirl Lottie Rawson (Joan Lorring) shows up and she threatens Kendall, too. And the next morning Kendall is found dead and the movie becomes a classic whodunit.

Turns out, three of the men—Emmric, Kendall and Russell—live across the street from Grodman in a rooming house run by the vaguely hysterical Mrs. Benson (Rosalin Ivan). She’s the one who bangs on Grodman’s window when Kendall can’t be roused, and Grodman is the one who busts the door open to find Kendall dead—knifed in the chest. But how? The door and windows were all locked. And there was no other exit.

Part of the fun is Grodman watching Buckley fumble the investigation. He brings in a thief (Clyde Cook) to theorize how a man could be murdered in a locked room, but the thief discounts all of his own suppositions. For a time, Lottie is his prime suspect. Clive has an alibi—he was on the train to Brockton—but then they find out: No, he was with a married woman but refuses to name her, and anyway Buckley finds circumstantial evidence in his desk, and he’s charged and sentenced to hang. Grodman travels to France in pursuit of the married woman. Alas, she’s dead. And all the while we begin to suspect Emmric. Why is he hiding in Grodman’s study? Why is he lurking in the stairwell outside Lottie’s dressing room? And isn’t he Peter Lorre? Surely, he did it.

Or did Grodman concoct the whole thing to make Buckley look bad?

Grodman concocted the whole thing to make Buckley look bad.

Kendall, you see, was drugged, not dead, when Grodman broke in his door. And when he sent the suggestive Mrs. Benson screaming for police, that’s when he killed him. He confesses all to Emmric in the end.

Again, it’s not bad, it’s just not quite right. Shouldn’t Grodman seem more insane to do what he does? In his review in The New York Times, Bosley Crowther gets it exactly right: “Neither gentleman approaches his assignment with apparent satisfaction or zest. Mr. Greenstreet is puffier than usual, and Mr. Lorre more disinterested and wan.”

Little bit

What I found of historical interest? During the Clive Russell jury deliberations, you have a mini-“12 Angry Men,” as one juror holds out on conviction. He doesn’t buy that a man could be smart enough to knife a man in a locked room but dumb enough to leave evidence refuting his alibi in his desk. But he folds more quickly than Henry Fonda.

Per 1940s Warners, we also get a song, sung from Lottie, in a music hall. It’s called “Give Me a Little Bit” by M.K. Jerome and Jack Scholl, and damn if it doesn’t prefigure, in almost litigious ways, Lerner and Loewe’s “With a Little Bit of Luck” from “My Fair Lady.” Particularly the “little bit” part. Which is the catchy part. I see no evidence that it ever led to a lawsuit. Maybe there were plenty of “little bit” songs? Maybe it’s too little of a bit to count as plagiarism? If “My Fair Lady” were released today, though, with “The Verdict” within memory, social media would be all over it. Not to mention IP lawyers.

Wednesday March 20, 2024

'Completely Off His Rocker'

“I think one of the failures of the media is that they've tried to explain Trump in the way you would explain a normal, healthy, or somewhat eccentric human being. But he is completely off his rocker. ... The problem we're going to have with Donald Trump—and I think the floodgates are going to open—is that people have tried to normalize him for too long. He is definitively, manifestly, unwell. He's a sick person.”

-- George Conway on CNN

Amen. The mainstream media, legit journalism—The New York Times, The Washington Post, WSJ and NPR—have had 10 years in which to figure out how to cover Donald Trump. They've failed. The Times in particular, particularly with their headlines or their focus, continue to soften his rough edges, normalize his abnormalities, or ignore his batshit craziness altogether. If Biden did 1/10 of what Trump did, it would be blaring headlines. With Trump, it's barely there.

Tuesday March 19, 2024

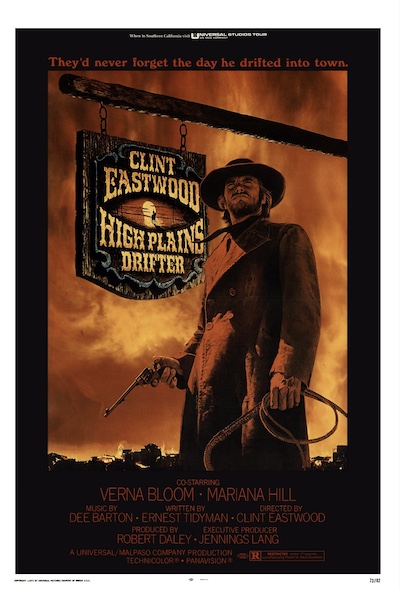

Movie Review: High Plains Drifter (1973)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Just as “Pale Rider” was “Shane” with an avenging angel, this is “High Noon” with an avenging angel. You have a town of cowards, newly released prisoners coming toward them, and a lone man with a gun. Right, it’s not exact. In order to be more exact, Marshal Will Kane, rather than imprisoning Frank Miller, would’ve been killed by Miller and his brothers, the town would’ve been complicit in the killing, and as “High Noon” began, Gary Cooper would’ve ridden into town to enact revenge: to humiliate every man and rape every woman, before killing his killers and then riding off into the sunset.

It's a little sick, to be honest.

In Clint Eastwood’s previous film, “Joe Kidd,” he outmans everyone. This is that on steroids. Every man is weak and sweaty but him. Every woman resists him until he kisses them. Nobody can shoot anything and he can shoot everything.

Oh, he also stands up for Indians and little people—as he stood up for Mexicans in “Kidd.” Who knew Clint Eastwood was our original virtue signaler?

Rape and a haircut

I think I first saw “High Plains Drifter” in the late 1970s, edited for television, but probably not edited enough. Even then it was a little unappetizing for me. Maybe I empathize too much with cowards or people who can’t shoot straight.

I think I first saw “High Plains Drifter” in the late 1970s, edited for television, but probably not edited enough. Even then it was a little unappetizing for me. Maybe I empathize too much with cowards or people who can’t shoot straight.

I’d forgotten the town was next to a picturesque lake. I’d obviously forgotten the name of the town, Lago, which is Spanish for lake. It hardly looks like a mining town—more like a future tourist destination, as it is: Mono Lake in the California Sierras. The shooting location was actually scouted by Eastwood himself. Then he had the town built there. The man in charge of construction/design was Henry Bumstead, who also built the town of Sinola for “Joe Kidd” and Big Whiskey for “Unforgiven.” He was an art director for 30 years, 1949-1979, then kept going with production design—though most of his work in the ’90s and ’00s was strictly for Eastwood. Which speaks well of Eastwood.

This is Clint's first western as director, and there’s an eerie, shimmering quality to it, augmented by an ethereal score, but also a blunt, sweaty palpability. The Stranger rides into town, past a graveyard that includes the names of Clint's past directors—Sergio Leone, Don Siegel—which is either homage or declaration of independence. Or both.

Everyone watches him and no one says a thing. Finally he goes into the saloon, orders a beer and a bottle, says he wants a peaceful hour in which to drink it. He doesn’t get it. Three yahoos interrupt him. Turns out they’re the men the town hired for protection against the three main baddies, Stacey Bridges (Geoffrey Lewis in his first Eastwood) and the Carlin brothers (Anthony James and Dan Vadis), who are about to be released from prison. But they’re yahoos, and for some reason—the same reason young subway juvies pick on Charles Bronson—they decide to pick on the tall, quiet stranger. He deflects and walks away—to the barber, a sweaty, shaking, man with a greasy combover (William O’Connell), for a shave and a bath. This is an iconic scene. Mid-shave, the yahoos appear. They taunt and threaten and attack. And the stranger shoots them all with the gun he’s holding beneath the barber sheet. (Hey, a little Han Solo from “Star Wars,” isn’t it?)

After that, we get the first rape. Callie Travers (Marianna Hill) bumps into him on purpose, chastises him, insults his manhood; so he takes her to a barn. Later, in his room, as he closes his eyes, he sees a man being whipped to death and begging the townspeople for help. This, it turns out, is Marshal Jim Duncan, played by veteran stuntman Buddy Van Horn, and the stranger is either his brother, his ghost or his avenging angel. The town is more than cowardly; it’s corrupt. Its mine is on government land, meaning none of the riches are theirs. Marshal Duncan planned on going public with it, so (I think) the town hired Bridges and the Carlins to kill him, then turned them over to the authorities. That’s why they’re worried about their return.

And that’s why they look to hire the stranger. He’s uninterested … until they say he can have anything he wants. “Anything?” he asks. So he keeps upping the ante. These boots, these blankets and candy for the Indians, a round of drinks on him. He makes the town dwarf, Mordicai (Billy Curtis), the sheriff. When the mayor laughs, he makes him mayor, too. He keeps requisitioning material: your barn, your bedsheets, your wife. He does try to train them—putting snipers on this and that roof—but they’re hopeless shots. Mostly he humiliates them. It gets bad enough that several band together to try to kill him. Instead, lighting a stick of dynamite with his cigar (a la Leone), he blows up most of the hotel.

Oh, and he has them paint the town red (literally), then renames it (unsubtly) “Hell.” And just before the baddies arrive, he leaves, going the other way.

And now it’s the baddies’ turn with the town.

That night, the stranger returns. Against a hellish backdrop of burning buildings, he whips one to death, hangs another with a whip, and takes down Bridges in a gunfight. As he leaves the next morning, exiting the way he entered, he passes Mordecai making a grave marker for the fallen Marshal. “I never did know your name,” Mordicai says, to which the stranger replies, “Yes, you do.” Then the camera pans to and holds on the tombstone.

So yeah, not the brother.

True spirit

According to Richard Schickel in “Clint Eastwood: A Biography,” the initial script IDed the Stranger as a sibling, and Clint started out playing it that way. But “I thought about playing it a little bit like he was sort of an avenging angel, too.” All of which adds to the ambiguity.

“High Plains Drifter” did well at the box office, while critics were mixed—though its Rotten Tomatoes score is 94%, with one of the rotten reviews ironically coming from Schickel. But it did gangbusters with teens of my generation. That, I remember.

Who didn’t like it? John Wayne. Again, from Schickel:

Clint recalls Wayne saying to him more than once, “We ought to work together, kid.” So when he found a script in which he thought they might costar Clint sent it on to Wayne, noting in his cover letter that the piece, though promising, needed more work. Too much more, in Wayne’s estimation. But in rejecting the proposal, he launched into a gratuitous critique of High Plains Drifter. Its townspeople, he said, did not represent the true spirit of the American pioneer, the spirit that had made America great.

Schickel sees this as “an argument between modernism and traditionalism, but I think it’s something more specific. “High Plains” riffs off of “High Noon,” which Wayne hated, because it’s a metaphor for the blacklist. Which he was in favor of. I think Wayne was still fighting that fight.

The movie is well-directed, cleverly directed, and the story is tight. It's just the other stuff I have a problem with. But apparently we will never tire of a seething moral righteousness given license to act immoral. We love that story so much we carry it into the world.

Monday March 18, 2024

Norman Jewison (1926-2024)

Yeah, I thought he was Jewish, too. It was the name, the fact that he directed “Fiddler on the Roof,” the kindly disposition. Go know.

He was nominated best director three times without winning, though one of his films won best picture: “In the Heat of the Night.” Jewison lost out to Mike Nichols, who'd directed “The Graduate.” Did that make it better for Jewison ... or worse? I assume the former but it's got to stick a little, particularly since that was a rare schism back then. The last time it had happened was 1956, I think: George Stevens got it for “Giant,” but “Around the World in 80 Days” won best picture. The Academy gave it to the old hand and the new tech. In 1967, they gave it to the new kid and the traditional fare.

His three nominations were in three different decades: 1967 for “Heat,” “Fiddler” in 1971, “Moonstruck” in 1987. What's his best? “Fiddler” is his highest-rated on IMDb (8.0), followed by “In the Heat” (7.9), then “The Hurricane” (7.6) and, oddly, “And Justice for All” (7.4). I say oddly because the day Jewison died, January 20, before we'd heard the news, we were watching “And Justice” and couldn't finish. We got halfway through. It just seemed too over-the-top to be interesting.

I should see “Moonstruck” again. It's a helluva oeuvre. He started out doing '50s TV, and not even the television playhouses. More musicals and glitz. Then he graduated to romcoms with a '50s veneer (“Send Me No Flowers”) before breaking bigger, or more serious, with Steve McQueen in “The Cincinnati Kid.” His mid-70s outpout is all over the place: from “Jesus Christ Superstar” to “F.I.S.T.” Meanwhile, Hollywood kept going to him, a Canadian, for movies about race in America: “In the Heat of the Night,” “A Soldier's Story,” “The Hurricane.” He was tapped for Malcolm X's story, too, but Spike Lee said nuh-uh. He kept getting entrusted with new stars: Stallone in '78, Nic Cage in '87, Robert Downey Jr. and Marisa Tomei in '94. Sometimes it worked.

Saturday March 16, 2024

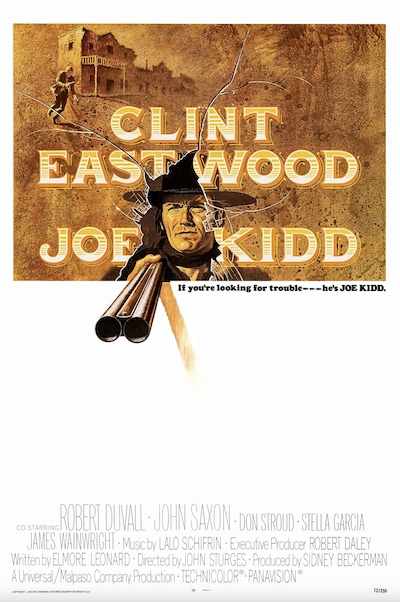

Movie Review: Joe Kidd (1972)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The town name is a joke, right? From screenwriter Elmore Leonard? Sinola? Apparently there’s a Sinaloa, Mexico, but this is New Mexico, circa 1902, and I’m not seeing anything. Or maybe I just don’t know shit from Sinola.

This is the movie Clint Eastwood made after “Dirty Harry” and it’s not bad, despite its 6.4 IMDb rating. Maybe it’s so low because Eastwood himself didn’t much like it, or didn’t like making it with director John Sturges, who was often drunk on set. Sturges, for his part, didn’t much like trying to direct Eastwood, either.

Do we even know what the title character does? We know he used to be a tracker and bounty hunter, and we see how he’s dressed, in tweed suit and derby, a more citified look than we’re used to from western Eastwood, but I don’t think we ever find out his current occupation. Cattle rancher, maybe?

Eastwood v. Nosotros

Joe Kidd begins the movie sharing a jail cell with two Mexican yahoos after getting drunk and losing a fight with Sheriff Mitchell (Greg Walcott). He begins down. He then proceeds to outman everybody. Whatever a man is, Joe Kidd is more:

Joe Kidd begins the movie sharing a jail cell with two Mexican yahoos after getting drunk and losing a fight with Sheriff Mitchell (Greg Walcott). He begins down. He then proceeds to outman everybody. Whatever a man is, Joe Kidd is more:

- He protects the townsfolk more than the sheriff

- He protects the Mexican people more than the Mexican revolutionary

- He’s more ruthless than the ruthless landowner

It’s the second one that made me shake my head. “Naw, don’t go there, Clint. Naw … Aw, fuck.”

He’s in the courtroom, sentenced to 10 days for the contretemps with Mitchell, when Mexican rebels, led by Luis Chama (John Saxon), burst in. They’re tired of losing their land to the Anglos; they’re tired of white men going back on their word. So Chama decides to kidnap the judge (John Carter) to make things right. Why the judge? Who knows? But in the confusion, Kidd rescues the judge, then, behind the bar of a saloon, sipping a beer and holding a shotgun, he waits for the Mexican rebels—in particular Naco (Pepe Callahan), with whom he’d had an escalating tete-a-tete in jail. Naco wouldn’t let the hungover Kidd have coffee, Kidd pours slop stew on him, Naco tries to clock him but Kidd knocks him out with the pan. He figures Naco wants revenge. He does. He doesn’t get it. Blam.

In the calm afterwards, the wealthiest man in New Mexico, Frank Harlan (Robert Duvall), shows up with an entourage of sureshots and jerks, and they attempt to hire Kidd to help them track and Kill Chama—whom Duvall keeps calling “Chay-ma.” Kidd begs off. He’s got nothing against Chama. But then he finds out Chama, as payback for Naco, invaded his ranch home, rustled his horses, and hurt his right-hand man. So off he goes with them.

Damn, if Naco had only let Joe have that cup of coffee.

Kidd regrets his decision quickly. The men reveal who they are, killing some Mexicans in cold blood, then, with leers, kidnapping Helen Sanchez (Stella Garcia), who, unbeknownst, is Chama’s girl. They take a small Mexican village hostage and shout out to Chama—hiding in the nearby mountains—that they’ll kill five hostages in the morning unless he surrenders himself. Then five at noon, then five at … .You get the idea. Harlan choose this moment, stupidly, to betray Kidd, who’s disarmed and put in with the hostages. But of course he finds some arms, kills some men, including the loudmouth Lamarr (Don Stroud), and brings the girl to Chama in the mountains.

Which is where she finds out Chama had no intention of sacrificing himself for the people below. Becoming martyrs in his name, he says, would be a good way to die.

The original script wasn’t like that. Per IMDb:

John Saxon said “Clint needed to be the guy who dealt with all the action, so in the end Chama was smeared with self-serving and cowardice, so it was clear who the main hero was.” Saxon attended a NOSOTROS meeting, a Latin American organization opposed to stereotypes, and publicly apologized for playing such a dubious character.

Then it just gets dumb. Chama doesn’t want to sacrifice himself but somehow Kidd convinces him to turn himself in? Kidd shouts down the deal to Harlan and everyone heads back to Sinola, but Harlan and his men stop a train to get there first. Oh right, one of the men, the sharpshooter Mingo (James Wainwright) stays behind to kill Chama and crew before they reach Sinola, but he’s killed instead. By Kidd. Who out sharpshoots the sharpshooter.

Jesus, Clint, leave something for somebody.

Judge, jury, executioner

In town, Kidd sends the rest of Chama’s men away (why?), then rides a train into the saloon and starts killing the bad guys. Then he tracks Harlan to the courthouse, and, from the judge’s chair, kills him in cold blood. After Chama turns himself in, Joe decks the sheriff. He tells him, “Next time, I’ll knock your damn head off.” Don’t really get his anger at the sheriff—who suddenly turns into a goober at this point. I guess it’s payback for the stuff we didn’t see at the beginning? It's outmanning everybody.

Beautiful scenery, though. And apparently the weaponry is very accurate for the time it’s set. Duvall is his usual impeccable, awful, oddball self. The gang is great, particularly Wainwright as Mingo, the sharpshooter, who’s both cool and casually cruel. I like Lynne Marta as Elma, Harlan’s concubine, who is kissed by Kidd in the early going and doesn’t mind at all. She’s cute. Died this year, sadly.

This was the phase of Eastwood’s career when he was popular with the crowd but called a fascist by the critics—before he became a critic and Academy darling whose movies did so-so box office. Before his movies became shitty and no one went to see them.

I get his appeal. It’s just problematic. In his next one, “High Plains Drifter,” it’ll be worse.

Friday March 15, 2024

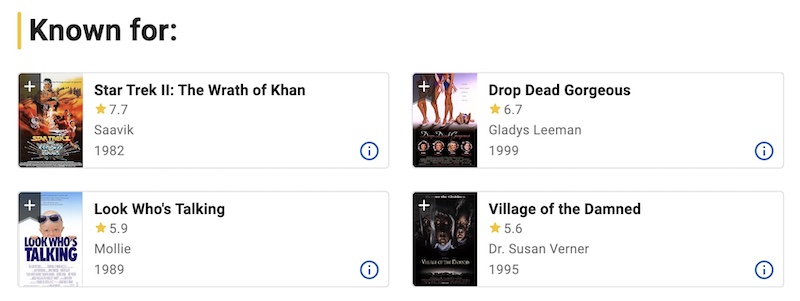

What Is Kirstie Alley Known For?

And I don't mean the late-life Trump craziness. Or the mid-life Scientology craziness.

Last month I watched “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan” for the first time in forever, and I was like, “Oh right, Kirstie Alley as Lt.—or Mr.—Saavik.” I'd forgotten how sexy she was. To be honest, I'd also forgotten she'd died in 2022—age 71. Cancer. But while perusing all of this on her IMDb page, I, inevitably, came across this.

What's missing from this “Known For”? Just what she's known for.

That algorithm really disrespects TV, doesn't it? That algorithm really disrespects us, doesn't it?

Thursday March 14, 2024

Movie Review: Oppenheimer (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Did anyone tell Christopher Nolan, as politely as possible, “Hey Chris, you might want to take a breath”? Probably not. Breathless is Nolan’s default.

Last summer my twentysomething nephews asked me which of the Barbenheimer films I liked best, and for a moment I pondered the joys and issues of both films before side-stepping toward what felt like the truer response: “I’m happier that ‘Oppenheimer’ was made.” It’s a movie for adults about some of the most serious topics of the 20th century: the creation of the Atomic bomb and McCarthyism. And it was done hugely and beautifully and released in the summer. My god, the summer! What a joy that is. How much we should be kissing Nolan’s ring for giving us a big, serious film in July.

And yes, you could say “Barbie” was a movie for adults about important topics. But it’s several times a fantasy whose interest in the end is about power and partying. “Oppenheimer” is about power and intellect. It luxuriates in smarts. It’s an ode to genius.

Chain reactions

“Oppenheimer” has three intercut storylines:

“Oppenheimer” has three intercut storylines:

- The main one: the journey of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) from studying quantum physics in Europe to leading the Manhattan Project and beyond

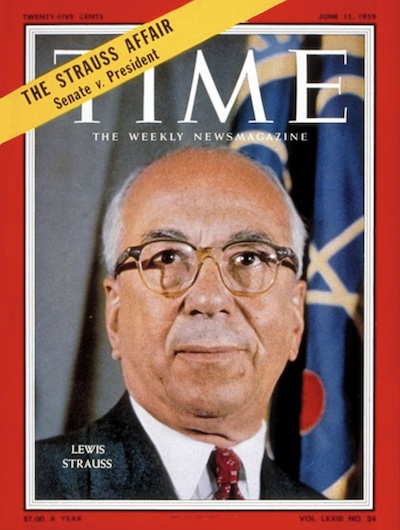

- His interrogation in a 1954 closed-door congressional session, masterminded by Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), that leads to his dismissal from government service

- Strauss’ interrogation before Congress in 1959, when his appointment as Sec. of Commerce is rejected

Live by the congressional hearing, die by the congressional hearing. That old saw.

Are there too many “gotcha” moments? Too many “reveals”? Oh, so Strauss isn’t a good guy? He’s the main villain? And David Hill, tossed up as a potential enemy, and whose clipboard Oppenheimer sends clattering across a train station floor, and, lest we forget, is played by Rami Malek, he stands up for him? And oh no, Oppie’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), is going to testify, but she drinks too much, and now she’s hemming and hawing and looking down at her lap and maybe itching to get the flask out of her purse as the prosecutor digs in. But wait! She totally turns things around! She makes him look bad and gets the congressmen on Oppenheimer’s side! Yay!

I also don’t get Alden Ehrenreich’s role. He’s supposed to advise Strauss during his congressional hearing but turns against him, or at least roots against him, when he finds out what a jerk he is. I guess he’s just there to signal what we’re supposed to feel. “Chris, what’s my motivation in this scene?” “You don’t have a motivation. You don’t even have a name.”

With all this carping, you’d think I didn’t like the movie. I did. It opened up (as much as anything could) the world of early 20th century quantum physics for me. And it was fun seeing characters excited to see Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh). Hell, it was fun seeing someone portraying Niels Bohr. Or Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer), Richard Feynman (Jack Quaid) or Edward Teller (Benny Safdie). And those are just the names I know. Imagine you’re a scientist watching this. It would be like me and “42”: Hey, Clyde Sukeforth! Cool!

So I liked all that and the early amazement at Oppenheimer’s intellect: learning Dutch in six weeks, knowing Sanskrit, reading Proust and Eliot and quoting Donne. And I just loved David Krumholz’s Isidor Rabi, the fellow Jewish-American physicist who humorously chastises Oppenheimer for learning Dutch while not knowing basic Yiddish, then feeds him like a Jewish mother. That’s a supporting role I could’ve seen expanded. I smiled every moment he was on screen. (Rabi’s relatives, apparently, felt otherwise.)

And when Matt Damon’s Col. Groves shows up? So fun. The “We need to get this done by any means necessary so get out of my fucking way” attitude, but with a glimmer in the eye.

Does the movie lose itself about 90 minutes in or did I just get tired? More, does the tripart structure (the trinity structure?) take away from the magnitude of the discovery—the moment when we realized that all that intellect and progress was just leading us toward global destruction? These are its last lines, a flashback to Princeton 1946:

Oppenheimer: When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world …

Einstein: I remember it well. What of it?

Oppenheimer: I believe we did.

Then he stares into the void and feels the horror of the accomplishment. Some have criticized Murphy’s performance as too wide-eyed and one-note, and, given everything Oppie did, he does feel passive. But Cillian is amazing for staring into the void and feeling the horror. (Cast him as Col. Kurtz.) But should that moment have been at Princeton 1946? Is there a reason it’s Princeton 1946?

The constant reference to Oppenheimer’s post-Hiroshima fame is a little odd, too. Before he visits Pres. Truman (Gary Oldman), he sees a TIME magazine cover story on him: Father of the Atomic Bomb. Then Truman greets him with “How does it feel to be the most famous man in the world?” Because of TIME? Oppenheimer’s TIME cover story was actually from Nov. 1948, not Oct. 1945, and its subhed is a little less grandiose: Physicist Oppenheimer: “What we don’t understand, we explain to each other.” He certainly got more famous. According to newspapers.com, “Robert Oppenheimer” was mentioned in seven articles in 1944, and 1,490 in 1945, but it doesn’t top 2,000 much. That’s not exactly “the most famous man in the world.” It’s science fame. He was famous for a scientist. His high-water mark, again per newspapers.com, was set during those 1954 security hearings, when he’s mentioned 22,042 times. You know who was written about more that year? Lewis Strauss: 30,504 times. He’s written about even more in 1959.

The constant reference to Oppenheimer’s post-Hiroshima fame is a little odd, too. Before he visits Pres. Truman (Gary Oldman), he sees a TIME magazine cover story on him: Father of the Atomic Bomb. Then Truman greets him with “How does it feel to be the most famous man in the world?” Because of TIME? Oppenheimer’s TIME cover story was actually from Nov. 1948, not Oct. 1945, and its subhed is a little less grandiose: Physicist Oppenheimer: “What we don’t understand, we explain to each other.” He certainly got more famous. According to newspapers.com, “Robert Oppenheimer” was mentioned in seven articles in 1944, and 1,490 in 1945, but it doesn’t top 2,000 much. That’s not exactly “the most famous man in the world.” It’s science fame. He was famous for a scientist. His high-water mark, again per newspapers.com, was set during those 1954 security hearings, when he’s mentioned 22,042 times. You know who was written about more that year? Lewis Strauss: 30,504 times. He’s written about even more in 1959.

The Strauss affair was a huge story at the time, written about constantly, not to mention historically important: the only cabinet nominee between 1925 (Charles B. Warren) and 1989 (John Tower) to be rejected. What I find fascinating? I’d never heard of it. I was born in 1963, sure, but I read a lot of history, and a lot about that period, and … nothing. Even in Robert Caro’s thousand-page tome, “Lyndon Baines Johnson: Master of the Senate,” it’s mentioned only once, and off-handedly, not to mention parenthetically. In the lead-up to 1960, LBJ had to placate both right-wingers “and the great Senate bulls (he paid off a lot of debts to Clinton Anderson by cooperating in Anderson’s efforts to defeat President Eisenhower’s nomination of Lewis Strauss to be Secretary of Commerce…”).

Should that have been the lesson of the film? If your power stays in the shadows, your legacy might, too? Or is that too “Amadeus”? Oppenheimer’s name continues to resonate while Strauss’ winds up in the dustbin. “Do you know nothing of my music?” It might’ve helped if Strauss had made music.

Teller’s hand

“Why aren’t you fighting?”

“Why aren’t you fighting?”

Kitty says this (repeatedly?) during the ’54 hearings, but it seems an odd question since Oppenheimer is never portrayed as a fighter. He’s a scientist who somehow falls into the Manhattan Project gig. (The film assumes he’ll get it—because he does—but I’m curious who else Gen. Groves considered, and why, in the end, he went with Oppenheimer.) Oppie’s a man with an open mind who listens to everyone around him and tries to keep the group together. Teller wants to work on his H-bomb theories? Sure. Have at. He’s a diplomat.

But since the film raises the question, what’s the answer? The obvious one is he feels the need to pay for his sins: A-bomb, Hiroshima, bringing us into the nuclear age, destroying the entire world.

I’m curious why he didn’t make more of the thin window between the end of the war in Europe (early May 1945, when our need for the A-bomb kind of ended) and the Trinity test (July). Was there too much momentum? I get the political calculus: You save countless U.S. GI lives and send a warning to the Soviets. But what was Oppenheimer’s calculus? To just see it through? Was it a bit of Stockholm Syndrome? He’d drunk the military Kool-Aid? Or did he, the perennial theorist, just want to see if it would work? Because if he’d wanted, he could’ve put the kibosh on it pretty quickly. Just resurrect the whole “Yeah, we might set the entire atmosphere on fire” scenario. “What are the odds of that?” “Oh, less than 10%.”

The most famous line Nolan has ever written, or filmed, is probably from “The Dark Knight”: You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain. Back in 2008, that felt like bullshit to me—in the film it comes out of nowhere—but, man, the times have proven it true. “Oppenheimer” adds an addendum: resurrection. For a time, J. Robert is the hero. But he lives long enough, and through reactionary times, to become the villain. Then the times shift again, his enemies are smited, and in the 1960s his wife stares daggers at Edward Teller’s proffered hand.

I suppose I should finish the book—it might answer some of my questions. I got 200 pages in last summer but got distracted. Either way, I’ll always have a fondness for the film. It’s the last movie I ever saw with my brother.

All previous entries

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)