Friday January 29, 2010

Three Stories with J.D. Salinger - Part II

Part II: My Summer of Salinger

I first encountered J.D. Salinger the way most of us did—when I was assigned The Catcher in the Rye in high school—but there was a time when I could read no one else. It was the summer of 1987. I’d just graduated from the University of Minnesota and was in love with a girl who was in Maine for the summer while I was about to leave for Taiwan in the fall. It felt like life was flowing in the wrong direction and I could do nothing to stop it. I felt bruised, and other authors kept pressing the bruised spots. Only Salinger consoled.

I didn’t re-read Catcher. I re-read Nine Stories and the Glass family stories, and then re-read them again. I read “Hapworth” in an old copy of The New Yorker my father had kept. I was so desperate I read a slim paperback, Salinger, published in 1962, which consisted of cold, critical thoughts on the author, but which contained references to Salinger stories I’d never heard of. “Personal Notes of an Infantryman”? “Slight Rebellion Off Madison”? The titles themselves sounded magical.

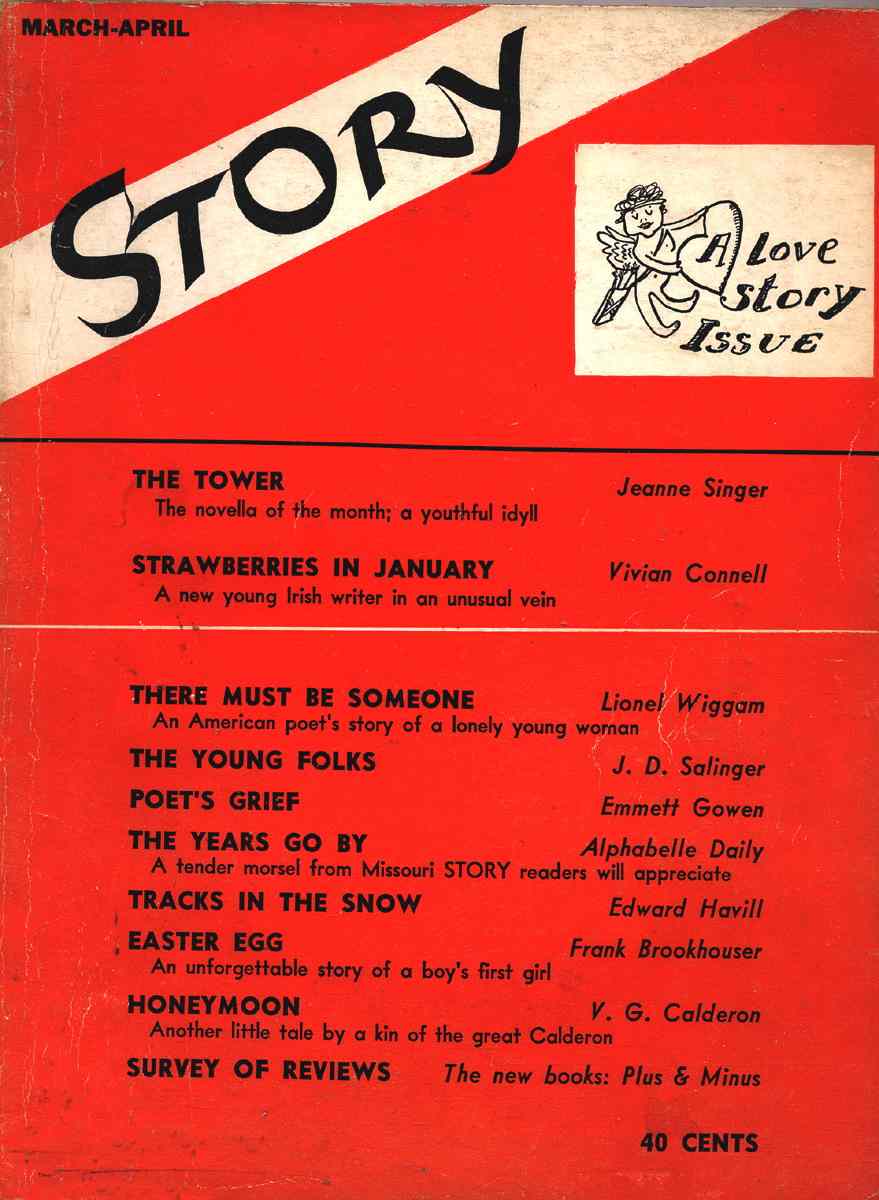

Turns out that before the nine stories of Nine Stories, as far back as 1940, Salinger had published stories, in magazines like Colliers and The Saturday Evening Post, that had never been collected in book form, and I found them at the University of Minnesota library.  Throughout that long hot summer, I kept returning to its cool, fluorescent-lit stacks to read about ‘30s kids at parties (“The Young Folks”) and young married couples with problems (“Both Parties Concerned”).

Throughout that long hot summer, I kept returning to its cool, fluorescent-lit stacks to read about ‘30s kids at parties (“The Young Folks”) and young married couples with problems (“Both Parties Concerned”).

It was hit or miss stuff. “Hang of It,” from 1941, concerns a World War I screw-up whose drill sergeant bellows at him, “Aincha got no brains?!” and the narrator sides with the drill sergeant. In the end we find out that the narrator is (“alley oop, I’m afraid,” as Buddy Glass would later write) the screw-up, now a colonel, and forever indebted to his loveable old drill sergeant. It’s the kind of thing Holden Caulfield would’ve torn apart.

War transformed Salinger’s writing. “The Stranger,” from December 1945, is blunt and unsentimental in comparison. “Your mind, your soldier’s mind, wanted accuracy above all else,” Babe Gladwaller thinks as he returns to New York to inform Vincent Caulfield’s girlfriend about his death. “So far as details went, you wanted to be the bulls-eye kid: Don’t let any civilians leave you, when the story’s over, with any uncomfortable lies.”

That’s right: Vincent Caulfield. He first shows up in “Last Day of the Last Furlough” from 1945, telling Babe: “My brother Holden is missing [in action].” Holden, not missing at all, not touched by war at all, shows up in two other stories from 1945 and 1946, while his much-imitated way of speaking—that repetitious, inarticulate way of circling closer to the truth, replete with I means and goddamns—shows up even earlier. In “Both Parties Concerned,” Ruthie leaves her husband, Billy, but she can’t stand staying at her mother’s place and returns. “It got me down,” she tells Billy. “I mean when I saw her looking so funny in her hair net again. I knew I wouldn’t be any good at home anymore. I mean not any good at their home.”

So many bells go off reading this stuff. In “The Varioni Bros.,” Joe, the more poetic half of a songwriting duo from the 1920s, dies horribly, tragically young—prefiguring Seymour Glass. In “The Stranger,” Babe’s relationship with his sister, Mattie, is right out of the Holden-Phoebe school. In “A Boy in France,” Mattie’s letter to Babe allows him to fall “crumbly, bent-leggedly, asleep”—as Esme’s letter would for a different soldier in “For Esme—With Love and Squalor.”

Eventually my love and need for Salinger became, like all loves and needs, stifling. I was reading 50-year-old stories that—beyond this epiphany or that moment of grace—didn’t take me anywhere I hadn’t been taken before, and better, by the same author. Occasionally I’d glance through these magazines to stories by the likes of Alice Farnham and Walt Grove and wonder whatever became of them. One issue of Story trumpeted the inclusion of “the 1944 Avery Hopwood prize novella, ‘Mexican Silver’ by Hilda Slautterback.” And it dawned on me—me who had such grand literary ambitions, but who had published exactly nothing—how hard it would be, not to be published and remembered like Salinger, but simply to be published and forgotten like Hilda Slautterback.

It was a Salinger reference that finally kicked me free from Salinger. In “A Girl I Knew,” the narrator mentions Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, and I sought it out. From there I read Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, and by then I was living in Taiwan and on a new trajectory.

Tomorrow: Seeing More of Seymour

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)