Vietnam posts

Thursday May 06, 2010

Our Vietnam Trip—Part IV: The Most Respectful Visitor to the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum

Andy: You’re not scared, are you?

Me: [Pause] Of course.

It was Wednesday morning, the power was out at Andy and Joanie’s place, and we were talking about a xe em ride into town. Xe ems are motorcycle taxis and the idea of riding on the back of one as it weaved in and out of Hanoi traffic was a little off-putting. But Patricia was getting a ride on Andy’s bike, and three on a bike didn’t make much sense (to westerners), so it was my next-best option.

It was actually a breeze. The roads we drove on weren’t superbusy. More importantly, traffic seems a lot less dangerous when you’re part of it rather than trying to cross it. The lesson, if one example can make a lesson, is a kind of modern Buddhist koan: Be one with the traffic.

We were let off, by Andy and the xe em driver, at Ba Dinh Square, which we had visited on Sunday, not knowing it was a Sunday, and which is an oasis from the traffic. On Hung Vuong, the road that runs between the three Ho Chi Minh sites and a wide expanse of manicured grass and footpaths, traffic is blocked off for two city blocks, so the pace of life is back to a walking pace. One is less assaulted by noise and pollution. This was particularly true when we visited last Sunday, not knowing it was a Sunday, since the place was virtually deserted, but it was less true Wednesday morning at 10:00, when an anaconda-sized line, filled mostly with schoolkids, snaked from the mausoleum’s entrance down to the southern end of Hung Vuong. The mausoleum, where Ho Chi Minh’s body was interred, was what we came for, since it was only open in the mornings, but I took one look at that line and my shoulders drooped.

“Maybe we should just bag this.”

“What do you mean?” Patricia said.

“We’re never going to get in.”

“Sure we will. Look, the line’s moving quickly.”

It was. I began to walk toward the back of the line; but an armed guard, seeing me approach, directed me to the other side of the street. The only foot traffic allowed directly in front of the mausoleum was the line of visitors who had already been through security. We needed to go through security. That was also at the southern end of Hung Vuong.

While waiting in line for that, Patricia suddenly spoke up.

“Oh no!”

“What?”

“This.” She fingered her sleeveless top.

“Did you spill on it?”

“It’s sleeveless.”

“Right.” The guidebook warned that men in shorts and women in sleeveless tops were not allowed in the mausoleum. It was why I was wearing long pants in 80-degree weather with 90% humidity. “Should we bag it?”

“Noo!” Patricia. sounded like a child who might be denied a roller-coaster ride. She left and returned a minute later with a black shawl covering her shoulders.

“How much?” I asked.

“Thirty thousand. Is that a lot?”

“A buck fifty.”

She fingered it. “It’s not bad for a buck fifty.”

At the security checkpoint, her purse and my book bag went through the x-ray machine. Then I was told I had to check my book bag.

“What’s the point of putting it through the x-ray machine if I have to check it?” I asked the world.

“Just do it,” Patricia said.

A half hour after we arrived, an hour and a half before the mausoleum closed, we finally got in line. Ten people ahead of us I noticed the two Dutch girls from our Ha Long Bay trip and we had a small reunion. Just ahead of us stood a westerner who appeared to be obeying the letter of the dress code if not its spirit. He looked like a pirate. He wore a kerchief on his head, and longish, scraggly hair in back. His beard was scraggly. He was scraggly. It was as if he’d just emerged from 40 years in the jungle.

Then he began speaking to the women in front of him in fluent Vietnamese.

I hadn’t met a westerner yet who knew more than a few phrases in Vietnamese so this was an impressive display. When they were done talking and joking and laughing, I asked him how long he’d been speaking Vietnamese.

“Japanese,” he said.

“Right,” I said. Idiot! I thought. How could I not recognize Japanese?

We talked a bit. He was born in Romania, grew up in Britain, had been living in Japan for the last 40 years. When he found out we were from Seattle he talked up seeing a Stones concert there a few years earlier. “Three thousand dollars but it was totally worth it,” he said. He got animated. Our conversation was flowing. Then a white-gloved guard motioned for us to be silent. Suddenly we were at the front entrance. Another guard motioned for us to take our hands out of our pockets and put them at our sides. We did. Everyone was quiet and docile and stiff as we marched from the light and heat of the day and into the cool darkness of the stone mausoleum. We walked up a flight of stairs where it got even cooler. No one spoke. The only sound was the shuffling of our feet as we walked single file into a small room, where, on the other side of a u-shaped walkway, Ho Chi Minh lay in state, famously, or infamously, against his express wishes to be cremated. His body was small and his face was smooth. He had the familiar white goatee and white tunic. Was it impolite to stare? Was that allowed? Moot point. A second later we were outside again, blinking in the sun.

“Wow,” I said, breathing out.

“Do you think his body was real?” Patricia asked.

“That was worth doing just for the experience of doing it.”

“I don’t know if he was real.”

“Could you do that in the U.S.? Have people shut up in front of the Lincoln Memorial? Would that increase the experience or lessen it?”

Our Wednesday turned out to be a replay of our Sunday. After the mausoleum we walked across town to meet Andy (and, this time, Joanie) for lunch, then walked back across town for more sites. We were getting pretty good at walking Hanoi. At least I was getting pretty good at walking Hanoi. Patricia, in the middle of a road, with an army of vehicles barreling down on her, still had the urge to flee. She held onto my hand for comfort and direction. She wasn’t one with the traffic yet.

The advantage of walking Hanoi, and consulting, every other block, your map of Hanoi, is that, without knowing it, you’re learning something about the long, sad history of Vietnam. Our route to lunch, for example, took us down Dien Bien Phu (the site of the French defeat in 1954) to Hai Ba Trung (the three Trung sisters, who led the first revolt against the imperialist Chinese in the first century A.D.), then a right onto Quan Su. After a quick jog onto Tran Hung Dao (a grand commander who repelled two Mongol invasions in the 13th century), we walked down Tran Binh Trong (a 13th-century general who preferred death to collaboration), then took a left onto Tran Quoc Toan (yet another 13th-century marytr to the Mongols), before finally walking up the small side street of Ha Hoi and the restaurant.

The Hoa Sua School for Disadvantaged Youth is a non-profit restaurant, housed in an old French colonial-style building, complete with winding, outer stone staircase, where young Vietnamese are trained in the arts of restauranting, and which Andy was reviewing for an online publication. Patricia and I arrived first and took a table in the courtyard in the shade of several leafy trees. The place is on a quiet back street, and, after our long march, it felt cool and comfortable. I could feel myself decompress as I sipped my beer. I also felt a disconnect. Most of the customers were affluent westerners, most of the wait staff Vietnamese in crisp white shirts. Against the French colonial backdrop, it didn’t take much to imagine yourself in the 1950s or 1920s; to imagine yourself on the set of “The Quiet American.” One wondered, not for the last time, what the war had been about.

After Andy and Joanie arrived, we talked about our walk to the restaurant.

“We kept seeing these mannequins wearing, you know, hip clothes, but with the zipper of the jeans undone,” Patricia said.

Joanie nodded. “The mannequins are western. But Vietnamese jeans don’t fit western mannequins.”

“You’re kidding,” Patricia said.

“I thought it was supposed to be, like, a sexy thing,” I said.

“They just don’t fit,” Joanie said.

“So why don’t they get Vietnamese mannequins?” Patricia asked.

“Probably for the ‘cool’ factor,” Andy said. “The west is cool.” He talked about seeing a national ad campaign that used a male model who looked more American than Asian.

“Like Taipei 20 years ago,” I said, sounding like a broken record.

“So even our mannequins are fat,” Patricia said.

Our walk back, in the greater heat and humidity of the day, was a slog, weighted down, as we were, with food, beer, and a greater sense of our own massive westernness. It didn’t help that we were backtracking. We were visiting Van Mieu, The Temple of Literature, just a few blocks south of where we’d been that morning, but it was a site Patricia had read about and was determined to see. It had been dedicated 900 years ago as a place of higher learning, and like most places of higher learning it was tough to get into. The Temple encompasses several city blocks, all walled in, and we hit it in the middle of the eastern wall and headed north. Bad move. The entrance is along the southern wall. We had to walk three-quarters of the way around to get in.

After wading through a sea of chattering schoolkids, all dressed in dark pants, white shirts and red kerchiefs, who occasionally broke out their English when they saw us coming (“Hello hello hello”), we walked through the main gate. Van Mieu is long and symmetrical and divided into five courtyards. In the first two courtyards there are paths to the left and right, gateways you step through on the left and right, and ponds on the far left and right. Patricia loved it, I was nonplussed. “What was the point?” I wondered. In the center of the third courtyard there’s a man-made pond, filled with man-made crap, and a few fish seemingly gasping for breath. “What was the point?” I wondered. Then I found the point. On either side of the pond is the Temple’s main attraction: ancient stone tablets, or stelae, weathered by time, that include the results of centuries-old national exams being carried on the backs of ancient stone tortoises. The oldest date from 1442 and 1448. Fifty years before Columbus.

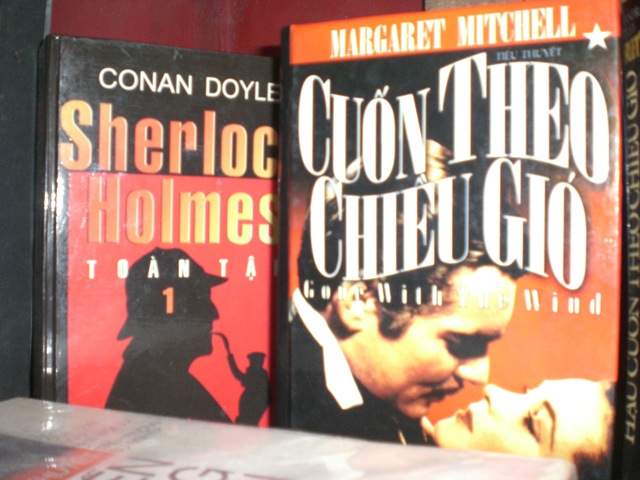

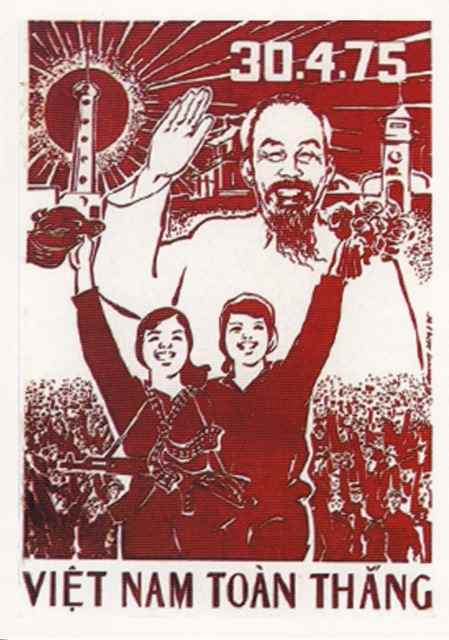

The fifth courtyard includes the National Academy, regarded, the Rough Guide writes, “as Vietnam’s first university, which was founded in 1076 to educate princes and high officials in Confucian doctrine.” Plus there’s a gift shop. I bought a set of postcards and (finally) Bao Ninh’s novel “The Sorrow of War,” but it was while browsing the rest of the books that I felt that disconnect again. In one hand I was holding propaganda postcards celebrating April 30, 1975, the date communist North Vietnam finally chased capitalistic American forces out of the South, and with the other I was sorting through business-oriented books with smartly dressed westerners on the covers. In Vietnamese. The less-smartly dressed Bill Gates was on another cover, “11 lo’i khuyen—danh cho the he tre cua,” while other examples of western culture were available for purchase: “Cuon Theo Chieu Gio” (“Gone with the Wind”), “Trang Non” (“New Moon”), and, thanks to Robert Downey, Jr., Sherlock Holmes. So how did we get from April 30, 1975 to “11 lo’i khuyen”? It’s as if hearts and minds are more easily won with promises of wealth and romance than with guns and bombs. Imagine.

Afterwards, Patricia and I walked across Nguyen Thai Hoc (the 20th century Vietnamese revolutionary who was executed by French authorities, at the age of 28, after the Yen Bai mutiny of 1930) to the Fine Arts Museum. The Temple of Literature had been outdoors, crowded, and hot. The Fine Arts Museum was indoors, empty, and hot. A few air conditioners sputtered here and there, but the building was old, the doors open, the rooms muggy. One wondered what such conditions were doing to the artwork on the walls, some of which was quite good, and obviously influenced by whatever artistic trends were big in Europe in the early part of the 20th century. After 1954 and Dien Bien Phu, though, the themes changed from the personal and universal to, basically, Uncle Ho: in the counryside, smoking a cigarette, with kids. Sometimes all three. It was awful stuff. It didn’t even have the vibrancy of official propaganda artwork—like in the postcards I had just bought. It felt like every artistic sensibility of every painter was smothered.

The power was still out when we returned to the Engelson’s place, and so, rather than dinner at home with Andy’s friend, Matt Steinglass, we took a cab back to the main part of the city, near Hua Lo prison, to a favorite restaurant of Andy and Joanie’s, Quan An Ngon on Quan Su. It was a noisy and vibrant joint, with tons of wait staff, and reminded me of the type of two-tiered restaurant Jackie Chan, in one of his mid-‘80s films, might get into a spectacular, acrobatic fight. I would forever after refer to it as “The Jackie Chan restaurant.” Andy, poor bastard, kept trying to refer to it by its real name, but no matter how he elongated and warped his mouth, he could never get the “Ngon” right. He’d give it a go, look over at Fiona, age 7, who would quietly shake her head and correct him before going back to her drawings.

The girls had crayons and paper out, the adults were drinking ba ba ba (“333” beer), the wait staff, as many as 7-10 people, crowded around the table. Quan An Ngon has great customer service but we got extra attention less because we were westerners than because we were westerners with children. It’s difficult in Vietnam, or in Asia, for westerners to blend into the background (“Hello hello hello”), but you do cease to exist if you enter a joint behind kids. All attention is on them. Is it too much attention? At one point, two of the waitresses crouched behind Fiona’s chair and began stroking her long blonde hair. Some part of me flinched, but Fiona kept drawing while Andy and Joanie didn’t bat an eye. They trusted Fiona to object. Matilda objects. She doesn’t like the attention. Once again I admired the calm of parents. I'm havng enough trouble just getting me through life.

During dinner—a dizzying, delicious array of spicy vegetables, seafood, and meats—Joanie told us her story, or Matilda’s story, of the Ho Chi Minh mausoleum. Andy hadn’t been yet but Joanie went with her daughters and visiting relatives, and they were told, yes, the same things we were told by the guards: be quiet, arms at sides, be respectful. Matilda, age 4, listened, nodded, walked in with the others in silence. Then they all walked out in silence. Then Matilda asked a seemingly relevant question: “Where’s Ho?” She’d been so quiet and respectful she hadn’t even turned her head to see his body lying in state. You could argue that Matilda Engelson, American, age 4, was the most respectful visitor ever to the Ho Chi Minh mausoleum. She was so respectful she hadn't even seen him. He wasn't even there. Which is what he'd wanted all along.

Monday April 19, 2010

Our Vietnam Trip—Part III: Ha Long Bay

I was originally against a sidetrip to Ha Long Bay. After spending nearly 24 hours getting to Hanoi, my thinking went, why pick up so soon and go elsewhere? Shouldn’t we see what’s there first?

Then I saw what was there.

We bought our tickets through the much-recommended head offices of iTravel. I.e., we walked into an expat bar, up a back staircase, and into a crowded second-story room where two women worked behind desks stacked with paper. It looked like a model of shadiness and inefficiency but was in fact the opposite. Most members of the tour group were picked up at their hotel in the Old Quarter, but we we were staying at the home of friends on other side of town, so we were told the minibus would pick us up at the nearby Sheraton at 8:15 Monday morning. It didn’t. Patricia and I walked over to the Sheraton early to use its ATM—Who wants to be a Vietnamese millionaire? Withdraw US$50—and as we were debating which parking lot might be the right parking lot for the pickup, a pretty woman in business attire and clipboard approached us, asked if we were... and pointed to some long-ass western names on her clipboard...then she took us by cab to the minibus outside the iTravel offices. It was not only great customer service, it allowed us to see Monday morning rush hour traffic in Hanoi. We’d arrived late Friday night, and had tooled around Saturday and Sunday without really realizing that the insanity we were seeing was, in fact, light, weekend traffic. The slow taxicab ride back to the Old Quarter set us straight.

“Holy shit,” I said, staring out the window.

The pretty woman was not our guide (“I’m sorry, honey,” Patricia mock-consoled me). Our guide was a peppy young Vietnamese man who had majored in tourism at a local university, and who, after telling us a little about himself, began the trip by asking the 11 foreigners on board to talk a little about ourselves. This was the first tour-group tour Patricia and I had been on, and we exchanged wary glances, but the introductions were quick and painless. Among our companions: an Aussie man, his wife and mother, traveling around Southeast Asia for several months; two Dutch girls traveling around Southeast Asia for several months; and a Swiss couple traveling around Southeast Asia for several months. Patricia and I were in Vietnam for two weeks. Nothing like American vacation time.

From Hanoi to Hai Phong Harbor, the launch point for Ha Long Bay, is only 170 kilometers, or 105 miles, but it took nearly three hours to get there. The road was bumpy, and only two lanes, which, by general consent, the Vietnamese had turned into three lanes: two thin lanes on either side for motorbikes and bikes and pedestrians, and a main lane, straight down the middle, where larger vehicles, heading in both directions, played chicken with each other.

From Hanoi to Hai Phong Harbor, the launch point for Ha Long Bay, is only 170 kilometers, or 105 miles, but it took nearly three hours to get there. The road was bumpy, and only two lanes, which, by general consent, the Vietnamese had turned into three lanes: two thin lanes on either side for motorbikes and bikes and pedestrians, and a main lane, straight down the middle, where larger vehicles, heading in both directions, played chicken with each other.

After leaving the city, we were soon driving past startling green rice fields tended by two or three Vietnamese wearing traditional garb and conical hats. It was a scene so quintessentially Vietnamese as to be almost embarrassing. It was like visiting America and seeing cowboys herding cattle, or visiting Holland and seeing Dutch girls in wooden shoes waving in front of windmills. You mean it’s really like this? Yes, it’s really like this.

We also drove past numerous thin, three-story buildings with colorful facades dotting the landscape. I’d seen plenty in Hanoi and assumed the design was a consequence of the city—you squeezed in where you could—but no squeezing was necessary in the countryside. These buildings weren’t even next to each other but sprouted as randomly as gopher heads popping out of holes: here, here, and over there. Only the facades of the buildings were painted, in bright pinks and purples and yellows, while the long, exposed sides kept their original cement gray. Our tour guide later told me that real estate in Vietnam cost more by the width. Thus the skinniness. Form may dictate content, but economics dictates form.

Our boat was called “The Calypso” and we spent a good deal of the 24 hours on board in its clean, dark-paneled dining room, tended by two Vietnamese men in white dress shirts and a Vietnamese woman in ao dai. All the tourists took a table and pretty much stuck with it: the Aussie held forth with the Europeans, a late-arriving Vietnamese family had their own table, while Patricia and I joined an American, Jonathan, a project manager with the International Red Cross in Indonesia, and his girlfriend, Noy, a restauranteur from Laos, who, though shy, corrected my mispronuciation of her country. (The “s” is silent: Lao as in wow.) She also became the fourth person, out of an eventual cast of thousands, to correct my Vietnamese pronunciaton for “thank you”: not cam ON but gam un! Or so it seemed.

Jonathan grew up in Providence, Rhode Island, and, though he’d been living abroad for decades, still had that distinct Northeast obliteration of the letter “R.” He had met Noy during a biketrip through Laos when he stopped by her restaurant in Vientiane. I was peppering them with questions—How did they get together? How long had they been together? Did he know the Red Sox had won the World Series? Twice?—when, somewhere during dessert, people pointed at the window and we all rushed out onto the prow of the boat.

On the Oregon coast, there’s a famous rock 235 feet high just off the shore at Cannon Beach called Haystack Rock, and that’s what the islands in Ha Long Bay reminded me of. Except they were bigger, greener, and more numerous. That was the most amazing thing. On an overcast, sometimes misty day, we kept plowing the water and the islands kept appearing, in greater shapes and sizes. I went slack-jawed. “There are one thousand, nine hundred and sixty islands in Ha Long Bay,” our guide told me proudly. He said in 1994 Ha Long Bay was listed as a World Heritage Site (by UNESCO). He said now it was in the running for another, more prestigious honor (I forget which). He said its name meant Descending dragon. “Really?” I asked. “Long means dragon in Vietnamese?” Before I’d arrived I’d been curious if there were similarities between the Vietnamese and Chinese languages—since the Chinese had ruled Vietnam for a thousand years—and I’d already come across a few instances: male and female, nan and nu in Mandarin, are nam and nu in Vietnamese. Now long for dragon. Long is not only the Mandarin name for dragon, it’s the Mandarin name for both Bruce Lee (Lee Shao Long) and Jackie Chan (Chen Long). In Asia, it’s dragons forever.

After weighing anchor with 40 other tour boats (I counted the next morning), we took a smaller motorboat over to “Amazing Cave,” a stunning, three-chambered, well-lit attraction, made less attractive by the sheer number of people visiting. You go to Ha Long Bay not only for the beauty but to get away from the crowds of Hanoi, but the early part of our walk through Amazing Cave was as crowded as any walk through the Old Quarter. There was also the oddity of the penguin-shaped trash cans scattered throughout. “Why penguins?” Patricia wondered. “Why not something more native?” At the same time, the caves can’t help but bring the kid out in you, recalling, as they do, “Tom Sawyer” and pirate stories. You look around and think, “This would be a good place to be a pirate.” Then you think, “It probably was a good place to be a pirate.”

After weighing anchor with 40 other tour boats (I counted the next morning), we took a smaller motorboat over to “Amazing Cave,” a stunning, three-chambered, well-lit attraction, made less attractive by the sheer number of people visiting. You go to Ha Long Bay not only for the beauty but to get away from the crowds of Hanoi, but the early part of our walk through Amazing Cave was as crowded as any walk through the Old Quarter. There was also the oddity of the penguin-shaped trash cans scattered throughout. “Why penguins?” Patricia wondered. “Why not something more native?” At the same time, the caves can’t help but bring the kid out in you, recalling, as they do, “Tom Sawyer” and pirate stories. You look around and think, “This would be a good place to be a pirate.” Then you think, “It probably was a good place to be a pirate.”

Back at the Calypso, we were given hot towels and an orange drink in the dining room, then met 10 minutes later by the side of the boat, where we all launched out into two-person kayaks and paddled over the bay, through a dark tunnel, and into the quiet of Monkey Island Bay. Longtime readers know, longtime knowers know, that the personalities of Patricia and myself, particularly on trips, tend to be divergent. She’s more of a Pollyanna while I’m a bit of a Grumpy Gus. Half full, half empty. Oh wow, this. Oh yeah, this. At home, too, whenever we drive somewhere, I drive, because I can’t bear the passive way she drives, and because she (mostly) doesn’t mind my more aggressive form of driving. But put us in a kayak together and this is what I heard from the front:

“What are you doing?”

“No, we’re supposed to go over there.”

“Are you even trying to steer?”

“What are you doing?”

Admittedly, I wasn’t, or we weren’t, the best steerers. I went for speed, then tried to compensate for direction, then overcompensated. We took the drunkard’s path to our destinations. “More exercise this way,” I said, seeing things half full for a change. Patricia, half empty, went unamused. But she loved Monkey Island, particularly when we paddled within spitting distance of a group of monkeys dangling from trees, one of whom jumped into the water and swam to shore. “I didn’t know monkeys could swim,” Patricia said, blissful. Then, as dusk fell, we followed the others back to the boat. Ours was the serpentine path. We barely beat the Vietnamese grandparents.

Dinner was great, and beautifully presented, and included shrimp dipped in a small side dish of salt, pepper and lime. P and Jonathan and Noy and I shared a bottle of wine, and afterwards we took our buzzes up on deck, sat on lounge chairs and gazed at the night sky and the island silhouettes surrounding us. The air was soft and warm. On the other boats in the bay you could hear karaoke being sung, and on our boat, below deck, several people laughed while fishing for squid. I was happy where we were. It felt just right.

The next morning, in fact, that was where I immediately went: up on deck, at 6:30 a.m., to write. I wasn’t alone. The Vietnamese family was already there. I should’ve taken this as an opportunity but I took it as an interruption.

“The Vietnamese,” I thought from the middle of their country. Vietnam responded accordingly. It began to rain on me.

Our second day, forecast as sunny, was like that, overcast and drizzly, and the planned excursion, a motorboat trip past a fishing village, was short and sad. How many tourist boats had the people in this fishing village seen that day, that week, that year? How soon do you despise the blank faces peering into and taking pictures of your lives?

But we mingled better that second day. I spoke briefly with the Dutch women, who hadn’t known each other before they began their trip, and who were heading next to southern China. The Aussie, Steve, who had lived in Shanghai and spoke some Chinese, gave them pointers. Steve was intriguing. On the first day, some passing fishing villagers were laughing and holding out their hands and pointing, and someone on the prow of the boat guessed at its meaning. Steve corrected them. “They’re making fun of my weight,” he said. But he said it so matter-of-factly, with no trace of animosity or self-pity, that it amounted to grace. Steve’s a teacher and a scholar, who, late into his 40s, is still working on his Ph.D. One gets the feeling he’s interested in too much to focus on one thing. He’s traveled the world, and spoke knowledgably about everything from the beauty of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho to the idiocy of the personalities on FOX News. He became interested in the U.S. at an early age, he said, through the U.S. Civil War. We also talked Aussie movies and in general we all acted like it was the last day of school, even though we’d only been together for a day. Contact info, for whatever it was worth, was exchanged. Then we were back in port and heading to Hanoi again.

During our day on the boat, particularly up top or on the prow, I’d occassionally hear something that sounded like a helicopter—a sound and image that’s intrinsically tied with American memories of Vietnam. But I wasn’t hearing helicopters. I was hearing the chugging of long Vietnamese motorboats delivering supplies. Of course, these boats, too, were evocative. They looked like the boat Captain Willard takes upriver in “Apocalypse Now.” Plus these boats flew the Vietnamese flag, which, with its yellow star and red background flapping in the wind, is itself evocative. It was always oddly thrilling seeing it. It was like being on the other side of a big Other. “That’s right,” I’d think. “I’m here.”

The lovely Patrica, up on deck.

Getting away from it all.

Not our boat. More of a "Never get out of the boat" boat.

Friday April 09, 2010

Our Vietnam Trip — Part II: Visiting Vestiges

The key to enjoying Hanoi, for me, was learning to cross the street.

Visiting a new culture, one is invariably reduced to a kind of infancy anyway. Suddenly one doesn’t know the language, the food, the unwritten rules. One can’t even say “hello” or “thank you” properly. This isn’t a negative so much as part of the reason for going. In his song “New Town,” Vic Chesnutt sings:

And a little bitty baby draws a nice clean breath

From over his beaming momma’s shoulder

He’s staring at the worldly wonders that stretch just as far as he can see

But he’ll stop staring when he’s older

And that’s part of why we travel. To feel this way again. To stare at the worldly wonders that stretch just as far as we can see again.

Learning to cross the street was part of this. Hanoi traffic is a constant, oncoming, evolving flow that can leave cautious foreigners standing by the side of the road for long periods of time. I remember it took me a year to figure out how to cross a wide, busy street in Taipei. (Basically: if you don’t look at the oncoming drivers then it’s their job to slow down or get out of your way; if you do look at them then it’s your job to get out of their way.) Things are slightly more civilized in Hanoi, and, on the first day, Andy gave us lessons: Move slowly, but with purpose, across the street; pause when necessary; and whatever you do, never step backwards. It’s the Hanoi traffic equivalent of: “Never get off the boat.”

Here's how my thinking on Hanoi traffic evolved during our stay. On the first day: My god, look at these crazy fuckers. On the second day: I can’t believe there aren’t more accidents. By the fourth day, the observation becomes a question: Hey, how come there aren’t more accidents? The lanes in Hanoi aren’t used as lanes, or even suggestions of lanes, and the mix of trucks, buses, cars, motorbikes, bicycles and pedestrians, weaving down the road, often into oncoming traffic, brush within centimeters of each other. Yet during our two-week stay we didn’t see one accident. We saw the aftermath of a minor one, a tipped motorbike in the middle of the road, but that was it. Why?

An answer begins to suggest itself when you realize there’s no road rage. In a certain sense the Vietnamese can’t afford road rage—otherwise they’d have nothing but road rage—but it goes deeper than that. To feel road rage one has to feel a sense of ownership: “This is my lane”; “That fucker cut me off”; etc. But in Hanoi the system works on accommodation or it doesn’t work at all. You go along to get along. Nobody owns anything. Hanoi traffic, it can be argued, is one of the most communistic things about modern Vietnam.

And that’s the key to crossing the road. That car or motorbike heading toward you doesn’t feel he owns the part of the road you’re standing on, so he doesn’t object to you standing there; he’ll go either to this or that side of you. It’s all a matter of anticipation and accommodation. Think of the traffic as a river and the pedestrian as a turtle (a symbol of longevity in Vietnamese culture), who moves slowly and purposefully, while the river, the traffic, flows all around him, until he’s on the other side.

And one is a kid again. Look ma, I crossed the street! By myself!

I had this feeling on our second full day in Hanoi when Patricia and I ventured out on our own. We’re walking people, and on this day we managed to walk from the city center to the old French quarter, then back to the Old Quarter to meet Andy for lunch. Afterwards we walked west again to some of the Ho Chi Minh sites. Many rivers to cross.

We began in the morning at Hoa Lo Prison, or the Hanoi Hilton, where U.S. servicemen were imprisoned and tortured from 1964 to 1973. To get there, Sen. John McCain, a Navy pilot, was shot down in Oct. 1967, parachuted into Truc Bach Lake in Hanoi, was pulled to shore and beaten by a crowd and then taken to a hospital, or “hospital,” for six weeks, before beginning two years of solitary confinement. To get there, Patricia and I took a taxi. The place cost John McCain six years of his life. It cost us 10,000 dong—or about 50 cents each. One feels guilty before even entering. One feels the way time reveals the absurdity of human events, the absurdity of the borders we construct.

Hoa Lo was built by the French in 1896, and most of the prison, now museum, is dedicated to the period when the French ruled and the Vietnamese rebelled and suffered. The American section is relatively small, and, though it should have come as no surprise to me, propagandized. Apparently the Vietnamese treated their American prisoners well. Apparently they let them play basketball and billiards and chess. They fed them sumptuous meals while sympathetic Vietnamese doctors tended their wounds. Apparently they didn’t torture them to extract information or use them as propaganda tools or break them with forced confessions.

The sign outside the gate (“Internal Regulations for Visit of Vestiges in Hoa Lo Prison”) warns, among other things, against frolicking in the prison. One hardly needs the warning. Hoa Lo is a grim place, made grimmer by the propaganda. The cells are small, dank, dirty, the barred windows tiny. The walls are crumbling. There’s a guillotine in the French section, John McCain’s flight suit under glass in the American. There’s a framed, colorful picture of a waving Santa Claus conducting a train full of Christmas trees and presents, supposedly drawn by American POWs, that is all the more depressing for its brightness and cheeriness. There’s a section on the many protesters of the war in Vietnam, including Norman Morrison, a Quaker who set himself afire in front of the Pentagon in November 1965, and who is something of a heroic martyr in Vietnam. His first name is misspelled: “Noosman.”

Two incidents stand out. The courtyard includes a small, open-air gift shop, which, one imagines, does little business—it’s like a gift shop at Auschwitz—but there are several books on display, including Bao Ninh’s “The Sorrow of War.” This is a novel almost every expat in Vietnam knows but I hadn't even heard of until the day before when I saw it on a display table in a museum/home in the Old Quarter. After Andy talked it up, I read the first sentence:

On the banks of the Ya Crong Poco River, on the northern flank of the B3 battlefield in the Center Highlands, the Missing In Action body-collecting team awaits the dry season of 1976.

I’m a believer in first sentences and this was a good first sentence. I didn’t buy the book then, but I was contemplating a purchase at Hoa Lo when a white-haired, heavy-gutted foreigner walked by and saw, among the offerings, two books by Barack Obama: “Dreams From My Father” and “The Audacity of Hope.” He went apoplectic.

“Bah!” he yelled, and turned the faces of both books down.

It was such an impotent gesture I laughed. Not just because it was silly. If this guy was what I thought he was—a FOX-News watching, possibly Tea Party attending dude—he'd missed a golden opportunity. Barack Obama’s books were just sitting there next to Ho Chi Minh’s books. Why not take a picture of their awful, awful commingling? Play the “guilty by association” card. See? Didn’t we tell you he was a communist? And Asian to boot!

Instead he made his impotent gesture.

When I laughed out loud, he turned in our direction and, unbeknownst to me, met with a withering gaze from Patricia—who is less political than I but knows a stupid gesture when she sees one. Some combination of my amusement and her condemnation stirred something in this guy and he actually put the books back, grumbling all the while, before retreating to his wife. You don't mess with Patricia's withering gaze. Glenn Beck, you're next!

The second incident occurred after we left the prison. We were walking up Hoa Lo Road toward Hai Ba Trung when a Vietnamese man left his motorbike, walked over to the prison and took a piss against the wall. Public health issues aside, surely this is bad form for such an important building. Put another way: Are there no external regulations for visit of vestiges?

The second incident occurred after we left the prison. We were walking up Hoa Lo Road toward Hai Ba Trung when a Vietnamese man left his motorbike, walked over to the prison and took a piss against the wall. Public health issues aside, surely this is bad form for such an important building. Put another way: Are there no external regulations for visit of vestiges?

Then we were off: two children, holding hands, trying our best to cross the street.

The French Quarter was my idea, because it was French, and thus might not remind me of Taipei 20 years ago; but the Frenchiest thing about it were some wide boulevards, a grand opera house, and, most interestingly, a few old buildings, scattered here and there, of scraped yellow paint, high, second-story windows bordered by long green shutters, and empty balconies. They felt romantic. They probably felt romantic even before they suggested a lost era.

After meeting Andy for lunch at Cha Ca La Vong in the Old Quarter—a restaurant that serves just one dish: fried fish, cooked at your table, with sticky noodles and greens and chili peppers—we left Andy again and walked, mostly via Phan Dinh Phung, to the Ho Chi Minh trifecta: House, Mausoleum, Museum. But we’d read poorly. The Mausoleum, housing Uncle Ho’s body—which has been preserved almost as long as mine has been alive (41 vs. 47 years)—is open only in the mornings. We were too late.

The House, though, where Ho lived and worked from 1958 until his death in 1969, was elegant in its simplicity. That’s its point. It stood on stilts next to a humid pond, and the rooms, which one could look at but not enter from outer  walkways, were filled with small, simple desks, small, simple bookcases, and pictures of Lenin and Marx. (But not Stalin; never Stalin.) In the giftshop, an oddity: a book, called “40 Bai hoc danh cho tuoi moi lon,” with a cute Vietnamese girl in a short skirt on the cover. It felt like finding a Britney Spears CD at Monticello, but apparently the title translates to “40 Lessons for Adolescence” and is considered educational. A Google translation of a Vietnamese review tells us the book encourages “the healthy growth of new young adults, using the animated story, a vivid and concise, analytical, presentation...” Some enterprising expat should put that description on a T-shirt.

walkways, were filled with small, simple desks, small, simple bookcases, and pictures of Lenin and Marx. (But not Stalin; never Stalin.) In the giftshop, an oddity: a book, called “40 Bai hoc danh cho tuoi moi lon,” with a cute Vietnamese girl in a short skirt on the cover. It felt like finding a Britney Spears CD at Monticello, but apparently the title translates to “40 Lessons for Adolescence” and is considered educational. A Google translation of a Vietnamese review tells us the book encourages “the healthy growth of new young adults, using the animated story, a vivid and concise, analytical, presentation...” Some enterprising expat should put that description on a T-shirt.

The Ho Chi Minh Museum is less simple. It’s in a grand, opulent building, and there’s a grand, opulent staircase that leads to a grand, gleaming statue of Uncle Ho in mid-greeting; but it’s the second floor, past the statue, that recommends the place. It’s basically in a wagon-wheel design, with different wedges of the wheel dedicated, not to Ho, but to artistic interpretations of different periods of the 20th century as they relate to Vietnam. One wedge, for example, takes familiar images from Picasso’s “Guernica,” and brings them to large, 3-D life. There are homages to Andy Warhol’s “Marilyn” and photos of Dizzy Gillespie. There are attempts to make art out of the refuse of the American War: barbed wire, maps, G.I. helmets. There is a mirrored copy of a newspaper whose headline reads, “VIETNAM TRIUMPHS,” and whose subhed adds: “Nixon Bows to Heroism and Humanity"—as we know he always did. Most memorably, there is a giant tilted table on top of which sit giant pieces of fruit—banana, pineapple, apples—and which, according to a nearby plaque, encourages the younger generation, in the name of Uncle Ho, to preserve the environment against aggressive and destructive wars. No mention of pollution indexes.

We cabbed it home from there. This was before we’d been steered toward Mai Linh or CP taxis, the safe taxis, and it was the one time we were ripped off, or obviously ripped off, in Vietnam. I forget the name of the cab company, but as we neared Andy and Joanie’s place the meter read 170,000 dong. (A little over $8.) We objected strongly, pretty sure this was off by 100,000 dong ($5), but we could only object in English, and in the end I wasn’t quite sure of the cost anyway, so I gave him 150,000 dong, which he was happy to get. He triumphed. I bowed to his heroism and humanity.

The lovely Patricia, offering you your choice of giant fruit.

Thursday April 08, 2010

Live and Don't Learn

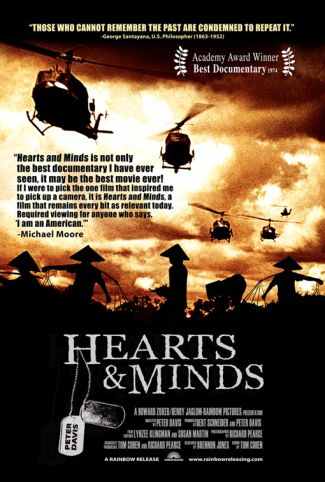

Interviewer: Do you think we’ve learned anything from [the Vietnam War]?

Former Capt. Randy Floyd: I think we’re trying not to. I think I’m trying not to sometimes. I can’t even cry easily—from my manhood image. I think Americans have tried, we’ve all tried, very hard, to escape what we’ve learned in Vietnam. To not come to the logical conclusions of what’s happened there. You know, the military does the same thing. They don’t realize that people fighting for their own freedom are not going to be stopped by changing your tactics—adding a little more sophisticated technology over here, improving the tactics we used last time and not making quite so many mistakes. I think history operates a little different than that. That those kind of forces are not going to be stopped. I think Americans have worked extremely hard not to see the criminality that their officials and their policymakers have exhibited.

Former Capt. Randy Floyd: I think we’re trying not to. I think I’m trying not to sometimes. I can’t even cry easily—from my manhood image. I think Americans have tried, we’ve all tried, very hard, to escape what we’ve learned in Vietnam. To not come to the logical conclusions of what’s happened there. You know, the military does the same thing. They don’t realize that people fighting for their own freedom are not going to be stopped by changing your tactics—adding a little more sophisticated technology over here, improving the tactics we used last time and not making quite so many mistakes. I think history operates a little different than that. That those kind of forces are not going to be stopped. I think Americans have worked extremely hard not to see the criminality that their officials and their policymakers have exhibited.

—from “Hearts and Minds” (1974), the Academy-Award-winning documentary by Peter Davis on the Vietnam War

Tuesday April 06, 2010

Our Vietnam Trip — Part I: Hanoied

The Chinese have a word for it: ru nao. I assume the Vietnamese have a word for it, too, but I don't know Vietnamese. I don't even really know the Vietnamese for “thank you,” which is the first word one should learn when staying in a foreign country: thank you, hello, please, I'm sorry, how much, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. I know something of the Vietnamese for “hello” (xin chao) and I know something of “thank you” (cam on), but Vietnamese is a tonal language, just as Mandarin is a tonal language; except Vietnamese has seven tones to Mandarin's four, and the Mandarin four are, in comparison, fairly straightforward: an even, musical tone (like “fa” on the musical scale), a rising tone, a falling tone, and a falling then rising tone. They’re numbered, too, which makes clarification easier. “Which tone?” “Third tone.” In Vietnamese the tones tend to swoop and soar and stop suddenly and pile on themselves. If tones are like stairs—one is usually in some process of rising or falling—Vietnamese tones feel like a series of stairs by M.C. Escher.

Ru nao, whose tones I’ve forgotten, and which has no direct English translation, means busy and bustling and crowded and noisy and hectic, and Taipei, Taiwan, where I lived in 1987-88, and again in 1990-91, was hen ru nao; but Hanoi, where my friends Andy and Joanie moved  last August, and which Patricia and I visited for the first time last month, is even more ru nao than my memory of Taipei. The city supposedly holds 6.5 million people, and four of them, Andy, Joanie, and their daughters, Fiona and Matilda, ages 7 and 4, live on the northeast side of Ho Tay, the giant lake to the north of the city, and are thus at a remove from some of this busyness. But it’s a short remove. Take a right out their front door, walk past the badminton court frequently in use by their Vietnamese neighbors, up a narrow alleyway that invariably smells of urine, and you’re in the thick of it again: the noise, the bustle, the sidewalks so crowded with parked motorbikes and piles of wires or mounds of dirt that they’re not much good for walking; the crazy traffic and constant beeping/honking off the Au Co. It is, in an English word, overwhelming, and in those first few days I felt overwhelmed.

last August, and which Patricia and I visited for the first time last month, is even more ru nao than my memory of Taipei. The city supposedly holds 6.5 million people, and four of them, Andy, Joanie, and their daughters, Fiona and Matilda, ages 7 and 4, live on the northeast side of Ho Tay, the giant lake to the north of the city, and are thus at a remove from some of this busyness. But it’s a short remove. Take a right out their front door, walk past the badminton court frequently in use by their Vietnamese neighbors, up a narrow alleyway that invariably smells of urine, and you’re in the thick of it again: the noise, the bustle, the sidewalks so crowded with parked motorbikes and piles of wires or mounds of dirt that they’re not much good for walking; the crazy traffic and constant beeping/honking off the Au Co. It is, in an English word, overwhelming, and in those first few days I felt overwhelmed.

Patricia was overwhelmed as well but in a good way. She is invariably game for anything, and she’d never been to Asia, so she kept saying: Wow, this. I am invariably game for little, and I’d had that history in Taipei, so I kept thinking: Oh yeah, this.

Oh yeah: these chalky tiled sidewalks made chalkier by pollution. Oh yeah: these dim fluorescent lights that cast a ghostly pallor over tiled rooms. Oh yeah: this humidity that curls the covers of paperback books and turns tile floors clammy. Oh yeah: this pollution that burns in the back of the throat. Oh yeah: ru nao.

On our first full day, Patricia, who had done the Lonely Planet reading (unlike some of us), wanted to go to the Old Quarter, with its narrow streets and small shops, north of Ho Hoan Kiem (Hoan Kiem Lake), and the Engelsons obliged. It’s often the first stop for foreigners, and it has its share of them, along with everything one associates with proximity to foreigners with deep pockets. All day the Vietnamese tried to sell us taxicab rides, pedicab rides, xe em (motorbike) rides, trinkets, watches, jewelry. A woman, wearing the traditional Vietnamese conical hat, and carrying fruits and vegetables on either end of the traditonal Vietnamese bamboo pole, tried to sell us her wares. When we begged off, she placed the bamboo pole on my shoulder. It was heavier than I anticipated and initially I thought she wanted help. Initially I felt chivalrous. Then she tried placing her conical hat on my head. Andy, half-abashed, explained that it’s a touristy thing. Foreigners get their pictures taken wearing her hat and carrying her load, and she gets money, and maybe sells them something. I went from feeling chivalrous to feeling appalled—less for her than for the tourists who do this kind of thing. At the same time, being appalled, and giving back her hat and pole as if they were diseased, didn’t exactly help her out.

Most of the streets in the Old Quarter are dedicated to one product, and their names reflect this. Hang Bac means shops of silver, Hang Dao ![]() shops of silk. We saw less silver and silk than shoes, towels, trinkets, art knockoffs, DVDs. The DVDs are knockoffs, too, bootlegs, and include movies that are still in theaters—most notably “Avatar,” whose DVD is set to be released in the States on Earth Day, April 22nd. I shouldn’t have been surprised by this but I was, and I wondered about its quality. A week and a half later, at the Ben Trahn Market in Saigon, curiosity got the better of me. The woman wanted 15,000 Vietnamese dollars (VND), or dong, for “Avatar,” but I offered 10,000 and she shrugged and took it. Basically I bargained her down from 75 cents to 50 cents. For a DVD of “Avatar.” That plays on U.S. systems. And isn’t filmed by someone in the back row of the theater but is a high-quality digital copy of the entire film. No wonder Hollywood’s worried. The DVD’s maker, if one wants to use that word, is a company called Simba, which promises “The Best Quality Trust," while the back of the DVD's packaging includes two impotent symbols: a copy protection label and an FBI anti-piracy warning. Our last day in Vietnam, back in the Old Quarter, I went a step further, asking for movies that hadn’t even been released into U.S. theaters yet. Did they have, say, “Iron Man 2”? They didn't, but, "Soon," the man promised. Then he offered “Alice in Wonderland,” “Repo Men,” “Percy Jackson.” He offered me the HBO Miniseries “The Pacific,” which, in the States, had aired only three of its 10 episodes. We should all be worried.

shops of silk. We saw less silver and silk than shoes, towels, trinkets, art knockoffs, DVDs. The DVDs are knockoffs, too, bootlegs, and include movies that are still in theaters—most notably “Avatar,” whose DVD is set to be released in the States on Earth Day, April 22nd. I shouldn’t have been surprised by this but I was, and I wondered about its quality. A week and a half later, at the Ben Trahn Market in Saigon, curiosity got the better of me. The woman wanted 15,000 Vietnamese dollars (VND), or dong, for “Avatar,” but I offered 10,000 and she shrugged and took it. Basically I bargained her down from 75 cents to 50 cents. For a DVD of “Avatar.” That plays on U.S. systems. And isn’t filmed by someone in the back row of the theater but is a high-quality digital copy of the entire film. No wonder Hollywood’s worried. The DVD’s maker, if one wants to use that word, is a company called Simba, which promises “The Best Quality Trust," while the back of the DVD's packaging includes two impotent symbols: a copy protection label and an FBI anti-piracy warning. Our last day in Vietnam, back in the Old Quarter, I went a step further, asking for movies that hadn’t even been released into U.S. theaters yet. Did they have, say, “Iron Man 2”? They didn't, but, "Soon," the man promised. Then he offered “Alice in Wonderland,” “Repo Men,” “Percy Jackson.” He offered me the HBO Miniseries “The Pacific,” which, in the States, had aired only three of its 10 episodes. We should all be worried.

For lunch we went to a street vendor for bun cha: grilled pork, sticky noodles, greens and peppers mixed and dipped in a broth. As a child in the Midwest, I liked to get everything onto one fork—meat, potatoes and vegetable—and bun cha is kind of like that. You want all the flavors between your chopsticks and in your mouth at the same time. (For a better description, go here.) Patricia loved it, loved eating on the street, laughed about the yoga positions required to sit on those small, blue, plastic stools before that small, blue plastic table. I thought the bun cha delicious, too, but wondered how we wound up at this place, and how clean it was, and what disease I might be getting. (Spoiler: none.)

The market in the Old Quarter.

You don’t realize the extent of the noise of Hanoi until you get out of it, and, after lunch, as Joanie took the girls for ice cream, Andy took Patricia and I to an expat joint: through a bar, up the back stairs, and onto a leafy terrace sheltered from the street. That’s when you feel your ears suddenly relax. Andy ordered his regular, ca phe sua da, or coffee (ca phe) with condensed milk (sua) and ice (da). Patricia followed. I went with an iced lime drink they called a shake. Later Andy took us through another bar and up some more back stairs to purchase tickets for trips later in the week. Then the three of us went to the Old Quarter’s market to buy food for dinner that evening. Patricia was in heaven—she loves markets—but this is precisely when I became fed up with Hanoi. The markets are even more crowded than the streets, and yet, through the narrow lanes, covered by dirt and slop, people still ride their motorbikes, beeping all the while. Could I stand here? No. Here? No. It felt like no matter where I stood I was in someone’s way. It felt like Vietnam was allowing me no place to stand.

Sunday April 04, 2010

Opening Day: Yankees vs. Viet Cong

In honor of baseball season starting tonight (at the moment: Yankees 5, Red Sox 1), I offer the following photo from the Ben Trahn Market in Saigon, which Patricia and I visited last Tuesday. Amid your Vietnam caps there was this. So much for Yankee Go Home. And yes, I was reminded of this.

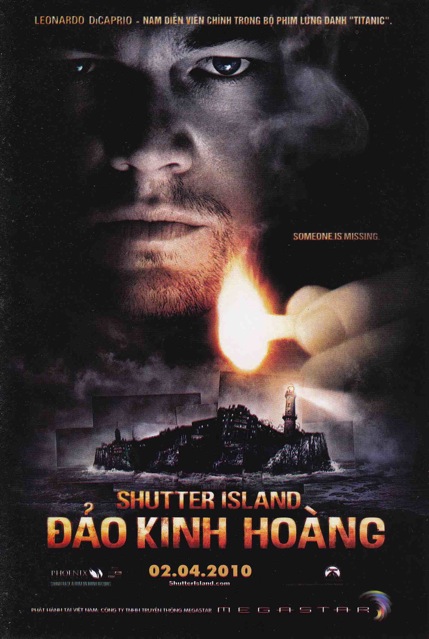

Saturday April 03, 2010

Someone is Missing

That someone is me—from here. For the past two weeks Patricia and I have been traveling in Vietnam. I meant to post about the experience as it happened but events conspired so I'll be posting from the cool of Seattle rather than the humidity of Hanoi. I know. It's a little like mailing your exotic postcards once you get home, but I'll try to avoid the suggestion of a Seattle city postmark and Liberty Bell stamp. In the meantime here's some movie lit I picked up at the VinCom City Towers in Hanoi. That opening date is April 2, by the way, not February 4. We didn't see it. We actually saw something else that day. But more on that later.

All previous entries

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)