Movie Reviews - 1990s posts

Monday December 03, 2018

Movie Review: The Phantom (1996)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Of all the 1930s ur-superhero reclamation projects attempted in the wake of the box-office success of “Superman” (1978) and “Batman” (1989)—i.e., Flash Gordon, Lone Ranger, and The Shadow—this would have been voted least likely to succeed. The Phantom is problematic for so many reasons:

- He’s a white guy treated as a god by jungle natives

- He’s considered “The Ghost Who Walks” (which is kind of spooky) yet dresses in a skintight purple suit and Robin mask (which isn’t).

- Plus: skintight suit in the jungle? For the weight-loss?

- Plus: purple suit in the jungle? For the camouflage?

- Plus: the jungle? Who gives a shit about the jungle?

The Phantom was a comic strip creation rather than a comic book or radio/pulp creation, and creator Lee Falk simply tacked on 1930s accoutrement (skintight suit/mask) to the tropes of decades-old boys adventure stories (jungle, signet ring, kowtowing natives, dog sidekick). Put it this way: The Phantom was backwards-looking in the 1930s. What chance did he have 60 years later?

The Phantom was a comic strip creation rather than a comic book or radio/pulp creation, and creator Lee Falk simply tacked on 1930s accoutrement (skintight suit/mask) to the tropes of decades-old boys adventure stories (jungle, signet ring, kowtowing natives, dog sidekick). Put it this way: The Phantom was backwards-looking in the 1930s. What chance did he have 60 years later?

More: The ‘90s output of Aussie director Simon Wincer’s wasn’t exactly inspiring: “Quigley Down Under,” “Harley Davidson and the Marlboro Man,” “Free Willy,” “Lightning Jack” and “Operation Dumbo Drop.” It’s like a film festival in hell.

Ditto its lead. Billy Zane showed up during the second season of “Twin Peaks” and everyone went “Movie star!” Then he made one bad film after another—culminating in the 1994 Italian spoof “The Silence of the Hams,” where he plays FBI agent Jo Dee Fostar opposite Dom DeLuise’s Dr. Animal Cannibal Pizza—and everyone thought, “OK, maybe not.”

And yet, for all that, “The Phantom” isn’t bad.

How The Phantom > Indiana Jones

There’s a light, humorous touch throughout and Wincer keeps things moving. We don’t get bogged down in the tons of backstory. Wincer, or screenwriter Jeffrey Boam, even saves the majority of exposition—the 400 years of Phantoms, and the latest, Kit Walker, is the 21st—for the very end.

Was Boam its saving grace? He wrote “The Dead Zone,” “Innerspace,” “The Lost Boys,” and “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade,” so he seems to know his way around a story. He begins this one a la “Raiders of the Lost Ark”: 1930s, jungle, treasure hunters—but with bad guys seeking the treasure. It actually upends, or clarifies, a disturbing point in “Raiders.” Indiana Jones, the guy we root for, voted the second-greatest cinematic hero of all time by the American Film Institute, is actually a thief. Worse: He’s a first-world thief robbing a third-world country. He’s robbing from the poor to give to a rich university. Maybe he’s due for some revisionism.

The bad-guy treasure hunters here are led by Quill (perennial bad guy James Remar, who will always be Ganz from “48 Hrs.” to me), who berates a small native boy, makes him drive a truck across a shaky rope bridge, and claims to have killed the Phantom. (He did: the 20th, Kit's father.) In a cave deep in the jungle, they lose one man in retrieving a skull with glowing bejeweled eyes, then are pursued, not by natives as in “Raiders,” but by a white dude in a purple skintight suit riding a white horse. It’s the intro of the Phantom and it should’ve been cool. It’s not. I wouldn’t be surprised if the scene was greeted with laughter in 1996 movie theaters. At the same time, I’m not sure what else you do. Maybe not have the bad guys spooked? Since, you know, there’s nothing scary about The Phantom. He’s just a dude in a purple suit on a white horse in the jungle.

That said, the action scenes are well-done, and the rope bridge—a favorite trope of serials—makes a solid reappearance. Zane supposedly worked out for a year for the role and did such a good job they dispensed with the padded suit. It shows. Back in his skull cave, we see him sitting shirtless, and there’s not an ounce of fat on him. He looks supremely, nonchalantly dashing. I immediately thought “movie star” again.

Another smart decision: The Phantom isn’t a god to the native people but a friend. There’s no “swaying the native mind” with tricks and illusions, as in the 1943 serial. At the same time, one wonders what The Phantom does with his day. The point of the old racist Phantom was to keep the tribes from fighting; his mere presence kept the peace. What does this one do? Just wait for white assholes to show up?

Kit soon learns from an ancient text that the purloined skull is one of the three “Skulls of Tuganda,” which, when placed together, “harness a force a thousand times greater than any known to man.” The Tuganda tribe used to own all of them, but they were attacked by pirates of the Sengh Brotherhood, and the skulls were separated and lost—four centuries ago.

Immediate thoughts:

- If the skulls were so all-powerful, how did the Tuganda tribe lose?

- Is the force a thousand times greater than any known to man circa 1938 ... or 1538? I was rooting for the latter. The power maybe of a grenade at best. Instead of apocalypse, it went pop and fizz.

The man after the skulls is Xander Drax (Treat Williams), a New York businessman/mogul with ties to the modern Sengh. Williams plays him as a kind of broad, comic Howard Hughes. It’s mostly welcome; other times a bit much.

Did Boam include too many characters from the strip? They all have to be introduced. Not just the girl, Diana Palmer (Kristy Swanson), recently returned to New York from the Yukon, but her would-be suitor, the useless Jimmy Wells (Jon Tenney), Lee Falk’s original consideration for the Phantom’s secret identity; and Diana’s uncle, Dave (Bill Smitrovich), an upright man who runs The New York Herald Tribune, and who tells Drax that they‘re running that exposé on him. Uncle Dave holds a soiree at his mansion, where we also meet Mayor and Police Commissioner, both of whom, of course, answer to Drax. As does the local mob bosses, the Zephro brothers. There’s a not bad scene where Drax gives a big speech in front of his lackeys about God being dead, America in financial ruin, darkness ruling the earth, and the opportunities in chaos. Ray Zephro (Joseph Ragno) objects. He talks about being an altar boy at St. Timothy’s and not putting up with this bullshit. There goes him. His brother, Charlie (David Proval), takes over. (Proval is mostly wasted here. You get no inkling of Richie Aprile.)

There’s also Sala (Catherine Zeta-Jones), whose all-female squadron works for Drax, and who will change sides before the end. Diana flies to Bengala to find out more about a spiderweb design (it’s the mark of the Sengh Brotherhood), but they’re forced down by Sala and her girls, and Diana is kidnapped. Enter the Phantom. Diana’s feistiness comes off a little bitchy. I.e., “Thanks, I can take it from here.” But they’re off and running.

So is the movie. At this point, it attempts, not poorly, the nonstop-action thing Spielberg perfected: From ship to plane to horse (a bit of a stretch—and ouch) to immediately being chased through the jungle by Quill and his men, guns blazing. Ultimately Phantom is helped by “the Rope People,” and he and Diana wind up back at the Skull Cave, where we’re introduced to yet another character, Capt. Horton (Robert Coleby), who tells Diana that the Sengh brotherhood is “an ancient order of evil. They started out as pirates. Nowadays, there’s no telling what they’ve become.”

Ah ha. NAZIS.

Probably, but we never get there. Apparently three movies were planned, but when this one opened to meh reviews (42% on RT) and meh box office (sixth place opening weekend), all that was scrapped.

Another smart thing the movie does? Gets Phantom out of the jungle. When I saw Kit Walker getting out of a cab in New York City, I got as excited as I did as a kid watching “Tarzan’s New York Adventure.” They don’t quite take advantage of it but it’s still fun: the run over the car rooftops in a traffic jam; stealing the cop’s horse; riding through Central Park and into the zoo, where, Tarzan-like, he’s apparently able to communicate with animals. Why not? Then we’re off for the movie’s final leg in the “Devil’s Vortex” (read: Triangle).

Lord of the rings

One of my favorite things about Billy Zane’s Phantom is his bemused matter-of-factness. “Your dog’s a wolf,” Diana tells him. “I know,” he responds. Here’s his first encounter with Drax:

Drax: All right, what's your name? Why do you want that skull so badly?

Kit: Kit Walker.

Drax: Huh. And who is Kit Walker?

Kit: I am.

On paper (or online) it doesn’t seem like much, but Zane nails it. He and Swanson also have good chemistry. She figures out who he is, of course—her college beau who left without saying goodbye. As Kit, he apologizes without apologizing. “My father died suddenly,” he says. “I had to take over the family business.”

The final battle in the pirate’s cove pits the three united skulls against the heretofore unmentioned fourth one: The Phantom’s ring. Guess who wins?

I’m not saying “The Phantom” is great, or even particularly good. But given all the problems with the source material, they didn’t do a bad job.

Friday February 05, 2016

Movie Review: Guilty By Suspicion (1991)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It should’ve been a slam dunk. A Hollywood movie about the blacklist (with its obvious heroes and villains) that was originally written by someone who had been blacklisted (Abraham Polonsky, “Force of Evil”), and starring one of the greatest actors of his generation (Robert De Niro).

So what happened? Why does it lie there?

I think it combines too many stories into too few characters in a way that doesn’t make sense dramatically or historically.

Take the opening. In September 1951, Larry Nolan (Chris Cooper) testifies in private session before the white-haired, fat men of HUAC—one literally smoking a cigar—and begs them not to force him to name names. “Don’t make me crawl through the mud,” he says. “They’re my friends.” It’s a powerful scene. The next time we see him, Nolan ruins a welcome-home party for director David Merrill (De Niro) by shouting, to the movie people gathered, “Who are we trying to kid? We’re all dead!” Then he goes home to burn books in his front yard—including, I should add, “The Catcher in the Rye,” which, since it had been published only two months earlier, was hardly on anyone’s list of “subversive” material yet. Upstairs, his wife, Dorothy (Patricia Wettig), drunk and hysterical, makes accusations and throws his clothes/typewriter out the window. It’s the stuff of melodrama. But that’s not the worst of it.

Take the opening. In September 1951, Larry Nolan (Chris Cooper) testifies in private session before the white-haired, fat men of HUAC—one literally smoking a cigar—and begs them not to force him to name names. “Don’t make me crawl through the mud,” he says. “They’re my friends.” It’s a powerful scene. The next time we see him, Nolan ruins a welcome-home party for director David Merrill (De Niro) by shouting, to the movie people gathered, “Who are we trying to kid? We’re all dead!” Then he goes home to burn books in his front yard—including, I should add, “The Catcher in the Rye,” which, since it had been published only two months earlier, was hardly on anyone’s list of “subversive” material yet. Upstairs, his wife, Dorothy (Patricia Wettig), drunk and hysterical, makes accusations and throws his clothes/typewriter out the window. It’s the stuff of melodrama. But that’s not the worst of it.

For the rest of the movie, Nolan becomes a major asshole. After naming his wife’s name, he sues her for sole custody of their child, and wins, since she, a former communist, is an unfit mother. (And he? No? Because he ratted?) She winds up alone, unemployable, and eventually kills herself in front of Merrill and his ex-wife, Ruth (Annette Bening), by driving her car off a cliff. At her funeral, Nolan doesn’t bat an eye.

This is a helluva 180: from begging “Don’t make me crawl through the mud” to throwing it on everyone without a thought. It’s like Nolan is two different people. Which he is.

The powerful opening scene is based on the 1951 testimony of Larry Parks (“The Jolson Story”), who used the “crawling through the mud” metaphor before HUAC in ’51, betrayed friends, and was blacklisted anyway. But he didn’t become a major asshole; he and his wife, Betty Garrett, stayed together. The second half of the 180? That’s probably based on someone like Elia Kazan, who named names but took a kind of neocon pride in it. Of his 1954 film “On the Waterfront,” he writes, “When Brando at the end yells . . . ‘I’m glad what I done!’ that was me saying, with identical heat, that I was glad I’d testified as I had.” (ADDENDUM: A better possibility is Budd Schulberg, the screenwriter of “Waterfront,” who testified against his ex-wife, Virginia.)

And you can’t do that. You can’t combine two very different people and think you’ve made a whole character.

‘Wait, with who?’

We have a bigger problem with our main character. David Merrill seems bright enough, but at times he’s about as sharp as Homer Simpson.

Merrill, a golden boy director, has the ear of studio chief Darryl Zanuck (Ben Piazza), and has just returned from a few months in Europe, ready to start his next picture. Then the party; then the book burning, where Nolan warns him about HUAC: “Wait until Karlin and Wood put your nuts in a vise.”

He doesn’t have to wait long. The next morning, Zanuck breaks the news:

We got a problem. I got a board of directors in New York, and ... I gotta listen to ’em when they tell me my movies won’t get played because some guy running for Congress has a hard-on for Hollywood. Business is lousy, the theaters are empty, everyone’s staying home to watch Milton Berle dressed up as a woman. And now this.

Merrill’s quiet response: “What do you mean, ‘Now this,’ Darryl?”

Zanuck then gives him the name of an attorney, Felix Graff (Sam Wanamaker, who was himself blacklisted), to get straightened out.

Merrill’s quiet response: “I’m sorry, Darryl, I don’t get this.”

Then he goes to see Graff in a dingy hotel room (to preserve his rep, Graff says), and Graff talks about clearing his name with the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Merrill’s response: “Wait. With who?”

Then HUAC stooge Ray Karlin (Tom Sizemore, playing essentially Roy Cohn) emerges from the shadows, and says, “It’s probably no surprise to you that your name has come up as a communist sympathizer.”

Yes. Yes, it is a surprise. “Wait a minute,” Merrill says, “I’m no communist. I went to a couple of meetings 10 or 12 years ago—that’s it.”

I guess the point is to show how innocent Merrill is. It takes him this long to get up-to-speed. But man is it boring.

Since Merrill refuses to cooperate, the Zanuck gig, and other gigs, disappear. People won’t take his phone calls; friends desert him. They accuse him. They think he named their names, since they know how much making movies means to him. That’s a dull little subplot, actually: Merrill realizing that he spent too much time on work, and not enough with family, and with his kid, Paulie (Luke Edwards, soon seen in “Little Big League”). So he amends his ways. He becomes a better father. Yay.

Eventually he goes to New York to see about work there. He visits old theater friends, the Barrons (Stuart Margolin and Roxann Dawson), but doesn’t let them know he’s been named. Which is, again, not smart. Doesn’t he get it? He’s got the plague. Everyone he’s with can get contaminated. A good scene at the Barrons’ apartment exemplifies this. It’s just Merrill and Felicia. She’s drinking, acting flirty, and lets him know Abe is away for the weekend. Then Merrill mentions he’s being followed by HUAC investigators. Talk about your cold water! She says the following in rapid order:

- “Do you think they followed you here?”

- “I think you’d better go, honey.”

- “And stay away from the theater, OK? I don’t want Abe to have any problems.”

She’s supposed to be awful in this scene, but he isn’t much better. His innocence is a liability.

Is De Niro a liability? He internalizes everything. He’s just there. When Martin Scorsese shows up in a small role as Joe Lesser (i.e., Joseph Losey), a director who flees to England to keep working, and gives us that Scorsese rat-a-tat-tat dialogue, it’s a relief. It’s pizzazz and excitement and life. As opposed to what De Niro is giving us.

The one lively moment with Merrill is when he gets a B western and begins directing again; he takes over and the cast and crew suddenly light up because they know they’re in the hands of a pro. But it calls attention to what’s been missing. The movie is about a guy who does one thing well, and we don’t get to watch him do that one thing. Which, yes, is the point. But surely there’s a better way to dramatize it.

An ounce of decency

That western, by the way, is another odd amalgamation. It’s a B version of “High Noon,” in which the lead is a young, B-list actor named Jerry Cooper, rather than an old, A-list actor named Gary Cooper. Jerry even tries to defend Merrill the way Gary did with Carl Foreman, “High Noon”’s blacklisted screenwriter; but Jerry, unlike Gary, has no clout, and the producer questions his loyalty. It leads to one of the movie’s best lines:

Jerry (angrily, to producer): If you want to call me a commie, you got to back it up!

David (quietly, to Jerry): Jerry, if he wants to call you a commie, he doesn't need to back it up.

In Polonsky’s original version, Merrill actually was a communist; but writer-director Irwin Winkler took over and turned Merrill into a fairly apolitical everyman. It pissed off Polonsky so much he took his name off the product and badmouthed the movie all the way to the theaters.

He was right. Even the final dramatic showdown against HUAC, with flashbulbs popping, doesn’t quite work. I like that Merrill doesn’t know what he’ll do until he does it. I also like the fact that the members of HUAC don’t back down even after he gets all Joseph Welch in their faces. “Don’t you have an ounce of decency?” he tells them when they ask about Dorothy Nolan. “Don’t you have an ounce of shame? She’s DEAD!” But, no, they don’t have any shame; they keep talking. As in life. What’s the significance of the line: “I know this hurts you, Mr. Welch?” It’s what Sen. Joseph McCarthy says after Welch asks him if he has no sense of decency. We think of Welch’s line as a game-changer; but it didn’t change the game immediately, only historically. In the moment, McCarthy kept attacking. Because he had no sense of decency.

Except Merrill can’t be Welch. Welch was an attorney sparring with McCarthy in 1954, not an accused director dealing with HUAC in 1952. Winkler has Merrill take a principled stand, and he’s followed by a friend, screenwriter Bunny Baxter (George Wendt), who takes the same principled stand: I will answer any questions about me but not about my friends. It’s seen as a kind of victory, this ending. Merrill and his wife walk out of the hearings in triumph. But can’t HUAC find Merrill and Baxter in contempt—as it did with the Hollywood Ten? Won’t they go to jail? Won’t they still be blacklisted for another 10 years? The movie wants it to be a happy ending but it isn’t. Hollywood wants the hero to come from Hollywood but he didn’t.

Thursday November 05, 2015

Movie Review: Rocky V (1990)

WARNING: SPOILERS

If “Rocky IV” was one of the most absurdly patriotic movies ever made—the taciturn and teeny American stoically avenging the death of his friend by taking on the huge Russian machine, Ivan Drago, in a boxing match in the U.S.S.R., and winning, and winning over the Russian crowd, including the Politburo—then “Rocky V” is one of the most subtly subversive, anti-patriotic movies ever made.

It begins, as with most “Rocky” movies, with the end of the previous “Rocky” movie: that moment of physical triumph and spiritual diplomacy: You can change, I can change, we can all change. Moments later, in the grimy Soviet shower, Rocky can’t stop his hands from shaking; then he calls Adrian “Mick,” even though Mickey died years earlier. At home, the doctors discover he’s suffering from cavum septum pellucidum. Basically, the Russian drove his brain to a spot where it shouldn’t be—not a bad metaphor for the Cold War, actually—but it means he can never box again.

Then he finds out he’s broke. All that prize money through the years? The mansion? The robot servant? Gone. While in Russia, Paulie gave power of attorney to their accountant, who used the money for his own real estate deals that fell through. Now Rocky has to return to the same old stinkin’ Philly neighborhood he fled after “Rocky II.”

Then he finds out he’s broke. All that prize money through the years? The mansion? The robot servant? Gone. While in Russia, Paulie gave power of attorney to their accountant, who used the money for his own real estate deals that fell through. Now Rocky has to return to the same old stinkin’ Philly neighborhood he fled after “Rocky II.”

In other words, because he fought for his country, Rocky 1) loses all of his money, and 2) loses his means to make money.

The obvious lesson from Sylvester Stallone? Never fight for your country.

Worst of the Rockys

Here’s how bad “Rocky V” is: Stallone’s son, Sage, who plays Rocky’s son, Robert, is the best thing in it.

In a scathing piece in The New York Times in 1985, Vincent Canby anticipated Stallone’s problems with a “Rocky IV” sequel:

The actor, who refought and won the Vietnam War in “Rambo,” has taken it upon himself to fight and win a war that hasn’t yet been declared—World War III. There’s nothing left for a “Rocky V” except a Miltonian confrontation with Satan.

So Stallone did the opposite. He did with “Rocky” what the Beatles did with “The White Album”: returned to basics. Except the Beatles made music out of it, and Stallone makes crap.

Let’s start with the notion that Rocky couldn’t make money off his name. Yes yes yes, in “Rocky II” he couldn’t act in a TV commercial with a nasty director. So what? Get a better director. Or do print ads. Or just monetize your brand, as they say today. Christ, he’s the two-time heavyweight champion of the world...and he’s white! Every doofus in the world knows you can monetize that shit. Instead, the movie pretends otherwise for the entire movie.

But at least Rocky starts up Mick’s Boxing Gym. That’s not a bad idea. Rock becomes Mick. It’s a livin’, not a waste of life. Then he takes on a brash kid from Oklahoma, absurdly named Tommy Gunn (real-life boxer Tommy Morrison), and then more absurdly nicknamed Tommy “The Machine” Gunn, because the real name isn’t perfect enough already. (It’s like giving a nickname to Coco Crisp.) And Rocky trains Tommy to be champ.

This is the centerpiece of the film. All of the movie’s remaining conflicts arise from this simple fact: Rocky trains Tommy. From that, we get this:

- Rocky ignores his own son, Robert Jr. (Sage), in favor of his adopted son, Tommy, in a way that everyone sees except Rocky.

- In the press, Rocky is given all of the credit for Tommy’s rise, and Tommy becomes resentful in a way that everyone sees except Rocky.

- A Don King-like boxing promoter, George Washington Duke (Richard Gant), steals Tommy away by plying him with something that famous professional athletes never encounter: women willing to sleep with them.

- Duke’s ultimate goal is to get Rocky back into the ring because he’s the only boxer that any boxing fan cares about. Apparently not enough to buy anything with his name on it, mind you, but certainly enough to watch him die in the ring. Because that’s entertainment.

Adrian (Talia Shire), who sees all of this happening, doesn’t say anything until the 11th hour, in an argument outside on Christmas Eve, in which Rocky talks up the smell of the neighborhood and yells, “I see where we are! I don’t want this no more!” within earshot of everyone who actually lives there. Classy, Rocko.

But eventually Rocky sees the light, and makes it up with Adrian, and Robert Jr., and Paulie, and they all go home happy. The end.

Oh right. The fight.

Brain and brain, what is brain?

It’s a “Rocky” movie so there’s gotta be a fight. But in all “Rocky” movies there has to be a reason that prevents the fight so we don’t get it until the end.

In “Rocky II” what prevents the fight is he might go blind if he fights; plus Adrian doesn’t want him to fight. But then he learns to fight right-handed and Adrian says “Win” and off we go.

In “III” he loses the eye of the tiger. But then Apollo Creed makes him live with black people so he gets it back.

In “IV,” I guess nothing really prevents the fight. He’s determined to beat the Russian as soon as Apollo is killed.

And in “V”? What prevents the fight is he might die if he fights. So how does Stallone overcome this dilemma? Well, Rocky just doesn’t die. He fights Tommy in the street because Tommy’s a little shit, and Duke doesn’t make any money off it. Of course, neither does Rocky. But he’s got family. Plus the old neighborhood. Which stinks.

Here’s the real resolution to that dilemma: Apparently Stallone gave Rocky cavum septum pellucidum because he planned to actually kill him off. But then everyone said, “No, you can’t kill him off.” So he didn’t. So Rocky fights with cavum septum pellucidum but his brain is cool with it. He doesn’t die.

But “Rocky” fans did a little bit. “Rocky V” drove our brains to a spot where it shouldn’t be.

Thursday September 03, 2015

Movie Review: Fantastic Four (1994)

WARNING: SPOILERS

For a famously bad movie, it’s not that bad. In some ways it’s better than the big-budget FF movies of 2005 and 2007. At least it has a campy charm and a few good lines about the psyche.

But yeah, on a normal day it’s godawful.

Examples of inexplicable, laugh-out-loud moments:

- Reed tripping Dr. Doom’s soldiers with an elongated foot.

- The Thing getting pissed off about the monster he’s become and leaving the Baxter Building; a second later, he is shocked, shocked, when two girls flee from him in terror. Poor Thing!

- The Invisible Girl turning invisible and ducking out of the way of bullets.

- The fact that the actor playing the Thing (Carl Ciarfalio) is much shorter than the actor playing Ben Grimm (Michael Bailey Smith).

But my favorite idiotic moment is earlier.

Love > Astrophysics

The movie starts with Ben, Reed (Alex Hyde-White) and Victor Von Doom (Joseph Culp) in college, while Johnny and Sue are just kids in “Mrs. Storm’s Boarding House,” where Reed and Ben rent a room. Sue is played by 13-year-old Mercedes McNab, and she has a crush on Reed. “He’s dreamy,” she says. Since we know they’ll wind up together, this is kind of creepy.

The movie starts with Ben, Reed (Alex Hyde-White) and Victor Von Doom (Joseph Culp) in college, while Johnny and Sue are just kids in “Mrs. Storm’s Boarding House,” where Reed and Ben rent a room. Sue is played by 13-year-old Mercedes McNab, and she has a crush on Reed. “He’s dreamy,” she says. Since we know they’ll wind up together, this is kind of creepy.

After Doom apparently dies in a scientific experiment involving the comet Colossus, we cut to 10 years later. Reed has figured out how to observe Colossus from aboard a space ship, with a gigantic diamond absorbing its energy and keeping them alive, and Ben agrees to pilot the ship. But what about the crew? Ben suggests Johnny and Sue, now in their twenties:

Reed: What do they know about astrophysics?

Ben: C’mon. They may not have Harvard diplomas but they know more about this project than anyone else on earth. Besides, if you don’t let them come, they will never forgive you.

Part of the blame for this goes to Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. In FF #1, they never did come up with a rationale for why Sue and Johnny were in the rocket ship. “I’m your fiancée! Where you go, I go!” Sue says as they drive to the launch site. “And I’m taggin’ along with sis—so it’s settled!” Johnny adds.

But my favorite idiotic moment is just after that. Inside the house, Johnny (Jay Underwood, overacting throughout) is excited, but Reed is still on the fence.

Johnny: Ready to go!

Reed: Actually, Johnny, I don’t think ...

Female voice (off camera): We’re ready.

And there she is on the stairs, Sue Storm, now played by Rebecca Staab, who was born in 1961 as opposed to 1980 for McNab. In 10 years, in other words, Sue has gone from being 21 years younger than Reed to just two. (I guess girls do mature faster than boys.) She and Reed stare into each other’s eyes as we hear tinkly piano music from a bad 1970s “Movie of the Week” love story, and everyone looks on with silly smiles. Then Reed says, “Absolutely! We’ve got a lot to do!”

That’s the moment. When Reed Richards lets Sue and Johnny fly into outer space because he’s in looooove.

Battle of the minions

The diamond is the key. It’s supposed to keep our four safe from the cosmic rays; but Doom wants it to power a laser cannon that will eventually destroy New York City, while the Jeweler (Ian Trigger), a decidedly non-cannon villain, wants to give it to the woman he loves, Alicia Masters (Kat Green), the beautiful blind sculptress we all know will become the Thing’s girlfriend. The Jeweler gets to the diamond first, but Doom laughs at this, ha ha ha, because it still works with his diabolical plans. Even better! Because now Reed Richards will suffer!

Or some such.

Not sure which villain has the worst minions. Doom keeps sending the same two guys, one of whom seems to be channeling Vito Scotti’s Dr. Boris Balinkoff from “Gilligan’s Island” (Bela Lugosi by way of Groovy Ghoulies), while both are accompanied by soundtrack music that seems stolen from John Williams’ “March of the Villains” theme in “Superman: The Movie”—the comic, bumbling tune that followed Ned Beatty’s Otis around. But I’ll take them over the nondescript Jeweler’s minions, who are sent to kidnap Alicia, the woman their boss loves, and they’re not exactly careful with her. The scene comes off like a PG version of rape.

Absurdities mount. Without the diamond, the four are affected by the cosmic rays and crashland next to a hill with a lone tree on the top, where we get low-budget revelations of powers. Sue disappears, Reed stretches, Johnny sneezes flames. “Just tell me what is happening to us!” Sue demands of Reed. Because no one arrives (“We must have dropped telemetry,” Reed says), they decide to camp out for the night. When they wake up, two things happen: 1) the Army arrives, and 2) so does the Thing.

But it’s not the U.S. Army; it’s Dr. Doom’s Army. For all his brains, it takes Reed a while to figure out they’re being held captive. After they escape, it takes him even longer to report back to the federal government. Meaning he never does. Nor does he wonder about being kidnapped in the first place.

The three storylines (FF, Doom, Jeweler) finally merge during the Thing’s Ringo-like wanderings. The moment the Thing is adopted by the Jeweler’s minions is the exact moment Dr. Doom shows up to take back the diamond. Cue epic battle!

Kidding. Alicia, being crowned “Queen” by the Jeweler, tells the Thing she loves him, and this, inexplicably, causes him to turn back into Ben Grimm. And this causes him to run away, get angry, cry in the night, then transform into the Thing again. Excuse me? If love makes him Ben again, why doesn’t he turn back at the end? No budget for transformation scenes, either, so we just get a spinning motion.

The big final battle is in Latveria, I guess. The Thing cries “It’s clobbering time!,” Reed battles Doom on the castle precipice, and the laser goes off, so Johnny—heretofore relegated to throwing fireballs—finally flames on, outraces the beam (nice trick), and stops it before it hits the Baxter Building.

How do they manage this special effect on such a low budget? The same way they made Superman fly in 1948: animation. It doesn’t look horrible.

Nothing to see here

This 1994 fiasco was never supposed to be released. It was only made so the producer, Bernd Eichinger (“The Name of the Rose,” “Nowhere in Africa,” “The Baader Meinhof Complex”), could retain rights to a movie he hoped to make with a bigger budget. That’s why he hired Roger Corman, King of the Bs, who could do it for $1 million instead of $30. Most of that apparently went into the Thing’s animatronic look. I’m guessing Sue got sloppy seconds and the Torch thucky thirds. The worst special effect is Reed’s stretching. It’s a lame superpower anyway—a holdover from when “plastic” was the new thing.

Regardless, someone in power should official release the 1994 “Fantastic Four” so the rest of us don’t have to rely on online or comic-con bootlegs to experience the suckiness. I mean, yes, it’s awful, but it’s hardly more embarrassing than the 2005 and 2007 versions.

SLIDESHOW

Wednesday April 02, 2014

Movie Review: Captain America (1990)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Hey, this doesn’t seem so bad.”

That was my thought 10 minutes into Albert Pyun’s “Captain America,” which was supposed to be godawful. The movie was made in the summer of ’89 for release in the summer of ’90 but it didn’t get released. It just disappeared. It was like they’d come up with a plague germ and needed to keep it isolated in a lab. Two whole years went by before it finally saw light, or a kind of light: it went straight to video. It was so bad that Cap’s co-creator, Jack Kirby, who fought to get his name on the film, fought, after the premiere, to get his name off it. More than 7,000 IMDb users have collectively given the thing a 3.2 rating. That’s the second-lowest-rated superhero movie ever, after “Steel,” starring Shaquille O’Neil. Right: worse than “Superman IV: The Quest for Peace,” “Supergirl,” “Batman & Robin” and “Catwoman.”

Yet, initially, it didn’t seem so bad to me. It helped that I’d just watched the 1944 and 1979 versions of Captain America, and this Captain America, at least, looked like Captain America: same uniform, same shield, same boots.  The origin of the Red Skull in Italy in 1936 had some decent production values, and they did their best to make the pre-Cap Steve Rogers (Matt Salinger, son of J.D.) seem skinny and weak. Sure, the opening scene is melodramatic while the stuff on the homefront with the girl, Bernie (Kim Gillingham), is sappy to the point of silliness; plus the southern accents of the military officers (Michael Nouri, Bill Mumy) are like out of some high school production of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” But 10 minutes in I wasn’t seeing godawful.

The origin of the Red Skull in Italy in 1936 had some decent production values, and they did their best to make the pre-Cap Steve Rogers (Matt Salinger, son of J.D.) seem skinny and weak. Sure, the opening scene is melodramatic while the stuff on the homefront with the girl, Bernie (Kim Gillingham), is sappy to the point of silliness; plus the southern accents of the military officers (Michael Nouri, Bill Mumy) are like out of some high school production of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” But 10 minutes in I wasn’t seeing godawful.

Then it kept going.

Shooting Captain America at the White House

Here’s the story. Remember: this is the story of Captain America.

It’s 1943. For his first mission, a month after being reborn, a nervous Cap parachutes into a castle in Nazi Germany, where the Red Skull awaits, kicks his ass, and ties him to a rocket ship aimed at the White House. And off it goes. But at the last minute, over Washington, D.C., Cap, still tied up, kicks at the missile and sends it to Alaska, where he’s buried in the snow and ice. The only witness to his heroics is a little boy with a camera, who, inspired, grows up to be the President of the United States!

Fast forward 50 years. In the 1990s, Cap is discovered by ...

OK, wait. Hold it right there.

So ... Captain America, the World War II fighting force, has only one mission during World War II? Which he fails miserably? Then he’s shot at the White House? And only averts complete disaster with some pathetic kicking? Which some boy witnesses from the ground? And considers heroic?

You could do this for the entire movie: reiterate its plot with disbelieving question marks.

After being unfrozen Cap wanders around the woods of northern Canada? And the only two people who find him are the fashion-model daughter of the Red Skull, Valentina de Santis (Francesca Neri), and Sam Kolawetz (Ned Beatty), the best friend of the president, now an enterprising reporter with assassination conspiracy theories? And they converge on Cap at the exact same moment? And Valentina shoots Cap but Sam saves him? Then Cap distrusts Sam and steals his truck and drives it to southern California? And he realizes he’s been frozen for 50 years only when he sees a thong bikini at the beach?

What the fuck?

Captain America is not only not a hero here, he’s not even known. Only two people know he exists: the Red Skull (Scott Paulin), who, from a castle in Italy, plots his nefarious schemes, including the assassinations of JFK, RFK, MLK, and the scuttling of Pres. Tom Kimball’s environmental bill; and Pres. Tom Kimball (Ronny Cox), who, when his childhood hero is resurrected, sends no one in the government, no Army, etc., to find him. Just his pudgy childhood friend.

Eventually Cap teams with Bernie’s daughter, Sharon (also Kim Gillingham), whom he initially thinks is Bernie. This creeps her out so she decks him. It’s supposed to be meet-cute; but at this point Cap has done nothing except lose fights so it just adds to the embarrassment. Then the Red Skull’s minions, who look like mobsters in a Dolce & Gabana ad, figure out where he’s staying and kill both Bernie, now aged, and Sam Kolawetz, the president’s best friend. Cap shows up too late for that. He’s been watching videos about assassinations. When the bad guys track Steve Rogers to the diner, Roz’s Café, where Cap was born, a fight ensues that Steve actually wins.

I.e., after 50 years and an hour of screentime, Captain America finally wins his first fight.

Then he and Sharon fly to Italy to confront the Red Skull in his castle, where, unbeknownst to Steve, although it’s worldwide news, the Red Skull has kidnapped and drugged (and somehow plans to replace) Pres. Kimball. But Cap saves POTUS and the two men, giving each other sappy thumbs ups, join forces in saving Sharon and stopping the Red Skull and ensuring the passage of a sweeping environmental bill. Then Sharon puts her head on Cap’s chest while Cap looks off majestically into the middle distance.

The End.

It’s like they hired a few professionals, readied some B- or C- or F-grade production values, then handed everyone a script written by a 9-year-old.

The question is: Who’s to blame?

Golan Depths

Is it screenwriter Stephen Tolin, who has 24 screenwriting credits, including “Masters of the Universe” (1987), “The Craigslist Killer” (2011), and a few episodes of the critically acclaimed series “Brothers and Sisters”? How about director Albert Pyun, who started directing schlock (“The Sword and the Sorcerer”), stayed in a different kind of schlock (Jean-Claude Van Damme movies) and reverted to various other brands of schlock (horror/revenge straight-to-video thrillers)?

Nah. It’s none of these guys. The blame goes to one man: Menahem Golan of Cannon Films.

Golan, along with cousin Yoram Globus, was responsible for some of the worst movies of the ’80s and ’90s. Apparently these guys had good intentions but a wide appetite. They wanted to make classy movies (“Barfly”), action-adventure (“Superman IV: The Quest for Peace”), and exploitation flicks (the “Death Wish” sequels), but were probably best at exploitation. Their eyes were always bigger than their stomachs. In two years alone, 1987 and 1988, Golan produced 44 movies. If one movie bombed, money disappeared for the others. And their movies were always bombing.

“It’s pretty difficult to make a film when there were times we actually had no money in the bank,” Pyun says.

The new Blu-Ray version of “Captain America” includes a sad featurette, “Looking Back at ‘Captain America,’” with Pyun and Matt Salinger. Both seem like decent guys. Salinger says the script’s best scenes were cut due to lack of funds. “Character stuff,” he calls it. “Nuance.” Pickups were supposed to be done in Alaska but they never went to Alaska. An over-the-top, melodramatic soundtrack was added to over-the-top, whooshing sound effects, which were set against some not-good actors working from a script that actually disparages the WWII legacy of Captain America. And that’s how we wound up with this.

“We did the best we could,” Salinger says, sounding the movie’s epitaph, “given the time we had and the money we had.”

The final insult? Near the end of the movie, with the Red Skull defeated, Cap looks briefly at the camera and smiles. What does it recall? What does it consciously remind us of? Why, Christopher Reeve, as Superman, smiling at the camera at the end of “Superman: The Movie.” That was one of the best superhero movies ever made. This one?

This one did the best it could given the time and money it had.

Monday August 06, 2012

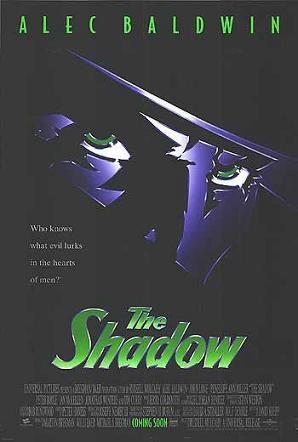

Movie Review: The Shadow (1994)

WARNING: WHO KNOWS WHAT SPOILERS LURK IN THIS REVIEW?

Of all the pulpy predecessors that Hollywood tried to turn into franchises in the wake of “Superman” (1978) and “Batman” (1989)—e.g., “Flash Gordon” (1980), “The Legend of the Lone Ranger” (1981), “Tarzan, the Ape Man” (1981), and “The Phantom” (1996)—the Shadow actually had a shot. For one, he’s cool. He’s got the long, dark trenchcoat flapping in the breeze, the fedora pulled low, the tendency, as with post-Eastwood action heroes, to shoot first and ask questions later. Plus his catchphrase is one of the greatest of the era: “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows, ah ha ha ha ha!”

“The Shadow” (1994), written by David Koepp (“Jurassic Park”; “Spider-Man”) and directed by Russell Mulcahy (Spandau Ballet’s “True”), has a shot, too. It opens the way of Tim Burton’s “Batman”: Bad guys are doing evil—in this case, throwing a Chinese scientist, who witnessed a crime, off a bridge—when a dark avenger appears, scares/kills the bad guys, announces himself, and then, as the music wells, poof, he’s gone.

Except, oh right, that’s not the way “The Shadow” begins. It begins in the opium fields of Tibet, where a man is being dragged into an opium den by two guys, who, a shot later, from inside the den, become two different guys (so much for continuity), and place the hapless man before an evil, shadowed warlord. We think the bad guy is being introduced here but it’s actually our hero, Lamont Cranston, played by a bare-chested Alec Baldwin wearing a long, straggly wig. An American doughboy during World War I, he stayed behind, turned to dope, and became this. He quickly demonstrates his evil ways by shooting both prisoner and trusted aid and leading his minions in laughter. But in the next scene he’s dragged from his bed and taken before a Tulku, or a Tibetan teacher, who says he will turn him into a hero. “You know what evil lurks in the hearts of men,” the Tulku says, “for you have seen that evil in your own heart.”

Except, oh right, that’s not the way “The Shadow” begins. It begins in the opium fields of Tibet, where a man is being dragged into an opium den by two guys, who, a shot later, from inside the den, become two different guys (so much for continuity), and place the hapless man before an evil, shadowed warlord. We think the bad guy is being introduced here but it’s actually our hero, Lamont Cranston, played by a bare-chested Alec Baldwin wearing a long, straggly wig. An American doughboy during World War I, he stayed behind, turned to dope, and became this. He quickly demonstrates his evil ways by shooting both prisoner and trusted aid and leading his minions in laughter. But in the next scene he’s dragged from his bed and taken before a Tulku, or a Tibetan teacher, who says he will turn him into a hero. “You know what evil lurks in the hearts of men,” the Tulku says, “for you have seen that evil in your own heart.”

That’s not a bad idea—the Shadow knows because the Shadow’s been there—but it’s all so poorly handled. Alec is already getting a bit doughy here, the wig looks ridiculous, and, most important, Cranston’s shift from doing evil to preventing it is handled off-stage. After Cranston battles a knife that comes to life, with a fierce, fanged face on the handle, he asks the Tulku if he’s in Hell. “Not yet,” the Tulku replies as the music wells. Then these words appear on the screen:

The price of redemption for Cranston was to take up man’s struggle against evil. The Tulku taught him to cloud men’s minds, to fog their vision through force of concentration, leaving visible the only thing he can never hide—his Shadow.

Thus armed, Cranston returned to his homeland, that most wretched lair of villainy we know as ....

New York City

Seven Years Later

Which leads to the scene on the bridge.

So how did the Tulku change him? Who knows? Why did the Tulku pick him? Who knows? The Shadow may know what evil lurks ... but we know shit about the Shadow. And we never find out.

Some of it still works. Each man the Shadow saves becomes part of his team, and each is giving a glowing red ring and a secret password (The sun is shining/But the ice is slippery); then they communicate through a Rube Goldberg system of pneumatic tubes crisscrossing the city. The whole thing has a secret-club/treehouse vibe to it. It’s appeals to the 8-year-old boy in all of us. “Kids, you can help ‘the Shadow,’ too!”

Plus: “clouding men’s minds” is basically the Jedi mind trick. Hell, I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s how it was ultimately pitched: “It’s Batman, dressed like Darkman, who can do the Jedi mind trick! Can’t miss!”

“It’s Batman, dressed like Darkman, who can do the Jedi mind trick! Can’t miss!”

It does. After the scene on the bridge, Cranston has dinner with his Uncle Wainwright (Jonathan Winters), the chief of police, at a swanky nightclub. Wainwright, echoing or foreshadowing complaints about Don Diego Vega, Bruce Wayne, et al., worries, without much sympathy, that his rich playboy nephew is wasting his life; then he gets word of another Shadow sighting and decides to appoint a task force to the vigilante. At this point, Cranston immediately retreats into the shadows, save for a strip of light across his eyes, and we hear the following:

Lamont: You’re not going to appoint a task force.

Uncle Wainwright: No. I’m not going to appoint a task force.

Lamont: You’re not going to pay any attention to these reports of The Shadow.

Uncle Wainwright: Ignore them entirely.

This might’ve been cool if it hadn’t already been done better 17 years earlier by Alec Guinness; if Cranston wasn’t doing it both family and the law; and if Winters’ line readings didn’t veer naturally toward the comedic.

A second later, Cranston meets Margo Lane (Penelope Ann Miller), who isn’t bad with the ESP thing, either, which is why he decides to steer clear of her. Ah, but fate. Shiwan Khan (John Lone), the last descendant of Genghis Khan, shows up in New York, via museum exhibit, and, determined to become the Emperor of the World, takes over the mind of Margo’s father, Dr. Reinhardt Lane (Ian McKellen, wasted), who works for the Dept. of Defense on a top-secret mission. Cranston pieces it all together, later, with the help of the Chinese scientist, Dr. Tam (Sab Simono), he saved on the bridge:

Tam: I guess you’d call it an implosive-explosive molecular device.

Lamont: Or an ... atomic bomb.

Tam: Hey, that’s catchy.

As with the above, tones are off throughout the movie. Opportunities are wasted. Shiwan Khan is evil with a capital “E.” At one point, he takes a cab, can’t pay, so he clouds the taxi driver’s mind to drive his cab into a gas tank, which explodes while Khan stands there laughing. Mwa-ha-ha-ha! It’s 1930s pulp villainy—right down to the race of the bad guy.

So the atom bomb is built, six years before the real thing, two years before we even entered the war, and Khan uses it to blackmail NYC for ... millions? Billions?

Billions.

Why the blackmail ruse? He’s just going to blow it up anyway. And why America? It’s 1939. Nazi Germany is on the march with its “master race” and lebensraum talk. Isn’t Hitler your true competition at this point?

The most laughable moment in the movie may be when Lane’s ne’er-do-well and randy assistant, Farley Claymore (Tim Curry), traps The Shadow in a water tank and fills it up with water. Cranston then communicates with Margo, over a distance of miles, to come to his rescue, but when she finally shows up and he’s completely underwater, he still needs to mouth, through the glass window of the door, the words “Open the door.” That should’ve been obvious without the ESP.

Baldwin coasts here. Lone overacts. Ultimately the movie comes down to a battle of minds, but who wants to watch minds battling? Even George Lucas was smart enough to give his Jedis, with their mind tricks, light sabres.

“The Shadow” isn’t horrific but it’s hardly good. In the end, Lamont kisses Margo, then walks off.

Lamont: I’ll see you later.

Margo: Hey, how will you know where I am?

Lamont (smiles): I’ll know...

God, that’s lame. The Shadow may know, but “The Shadow” knows shit.

“The sun is shining.” “But the ice is slippery.”

Monday November 14, 2011

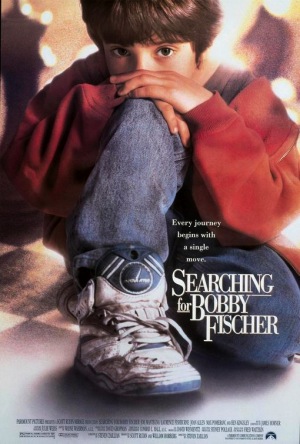

Movie Review: Searching for Bobby Fischer (1993)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Searching for Bobby Fischer” is a traditional three-act story of rise, fall and redemption. Its first act, like the first act of a superhero movie, contains the dawning realization of power: the chess prowess of seven-year-old Josh Waitzkin (Max Pomeranc), who may be the next Bobby Fischer. In the second act, Josh acquires two teachers: Vinnie (Larry Fishburne), a speed-chess hustler at Washington Square Park in New York, who fascinates Josh, and who represents a style of chess that is aggressive, streetwise and American; and Bruce Pandolfini (Ben Kingsley), a national master at the Manhattan Chess Club, who is hired by Josh’s father, Fred (Joe Mategna), to teach Josh, and who represents a style of chess that is cautious, erudite and European. The two styles and teachers clash, of course, and a rival—seven-year-old Jonathan Poe (Michael Nirenberg)—is discovered, and fear is introduced. That’s why the fall. It’s only when Josh intuitively combines the two chess styles in the third act that redemption is possible and final victory achieved.

I saw the movie when it was released in 1993 and liked it. I saw it recently, after Patricia and I watched Liz Garbus’ excellent HBO documentary  “Bobby Fischer Against the World,” and was disappointed. Immediately.

“Bobby Fischer Against the World,” and was disappointed. Immediately.

The film, based upon a true story, opens with kids playing hide-and-seek in Washington Square Park. We focus on the birthday boy, Josh, doe-eyed and big-shoed, who runs, hides under a bush, and finds a chess piece there, a knight, lying on the ground. He looks around. He sees men playing various games, vaguely trash talking. Then, reflected in the sunglasses of one of these men, he sees a chess board, and the soundtrack music rises triumphantly. That’s when my heart fell. The moment just doesn’t happen; the moment is crowned with music. In case we might miss it.

The movie keeps doing this. It keeps nudging us. It’s written and directed by Steven Zaillian, based upon Fred Waitzkin’s book, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Zaillian or some studio hand kept bringing up “The Natural,” the Robert Redford film, as a model. The movie is similarly nostalgic, even though its time-frame is recent if unspecific; it’s similarly melodramatic, even though it’s about a real boy rather than a mythic creation. We keep getting magic-hour light, too. That’s probably why its only Oscar nomination was for cinematography. The Academy can’t get enough of magic-hour light.

So is the opening scene the first time Josh discovers chess? We don’t know. When does he become friends with Vinnie? We don’t know. When does his mother, Bonnie (Joan Allen), no longer fear the Washington Square hustlers, as she does initially, but actually prefer them to the uptight and unlikable Bruce Pandolfini? We don’t know.

We don’t get any of that. Instead we get adult reactions and arguments about what to do with Josh. Should he focus completely on chess? Should he focus on it at all? Is Vinnie’s aggressive brand of speed chess ruining Josh’s game, as Bruce contends?

In the middle of a school conference, Josh’s grade-school teacher (Laura Linney) suggests—with everyone, including Josh, within earshot—that Josh needs to think about more than chess. She suggests he’s becoming isolated. Is he? We never really see him in his day-to-day so we don’t know. But we do know that Fred makes sense when he tells her (again, in front of everybody) the following:

He's better at this than I've ever been at anything in my life. He's better at this than you'll ever be at anything. My son has a gift. He has a gift, and when you acknowledge that, then maybe we will have something to talk about.

Good lines. The question is what do you do with it? How do you bring out the gift? The movie ultimately favors a “Let Josh be Josh” strategy. Josh’s second-act fall occurs not only because he fears his new rival but because the game stops being fun for him. Vinnie is fun; Bruce is not. Vinnie hangs outside; Bruce is almost always seen in airless rooms. Vinnie is cool, relaxed, wears weightlifting gloves for no discernible reason; Bruce is erect, tight-lipped, and encourages a contempt for the world, and for Josh’s opponents, that is the opposite of Josh’s natural decency.

So Josh begins to lose. On purpose. Because it’s all too much.

How does Josh revive in the third act? Again: who knows? His father brings his trophies into his room (“These belong to you”), which is a kind of metaphoric gesture (I.e., your talents belong to you, not to me or any other adult). Then he takes him back to Washington Square Park for a game with Vinnie. Then suddenly we’re in Chicago for the nationals, both teachers in tow, where Josh wins by utilizing both teachers’ strategies and by being himself. He offers his rival a draw, for example, before he beats him. In the midst of cutthroat competition, he remains decent.

I actually believe this to be a true lesson: To achieve true success, one has to be as authentically oneself as possible.

I also believe this to be a false lesson. The film implies that to succeed at the highest levels one need not sacrifice anything. Before the tournament, unlike the other poor kids chained to their chessboards, Josh goes on a two-week fishing trip with his father. At the end of the movie, we’re told that Josh, the real Josh, is currently the highest-ranked player in the U.S. under 18. “He also plays baseball, basketball, football and soccer, and in the summer goes fishing,” we’re told.

Sacrifice schmacrifice.

I wanted to like “Searching for Bobby Fischer” again, but it’s too sweet, too false by half. It forces structure onto a real story and wrecks it. I don’t know if the real Josh Waitzkin went through a rise/fall/redemption cycle but we do know that the real Bruce Pandolfini was Brooklyn-born, easy-going, and popular with his students. Unfortunately a film needs conflict and drama, and Kingsley’s Pandolfini is the route they chose. Shame. It’s sad when a movie is based upon a true story and you walk away thinking, “I didn’t buy it.”

Sunday October 30, 2011

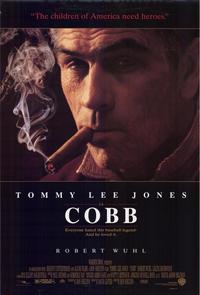

Movie Review: Cobb (1994)

WARNING: SPOILERS

A common conversation among movie buffs is which actor you’d like to play you in the movies. A less common conversation is which actor you wouldn’t. I’ll start that one. I wouldn’t want Robert Wuhl to play me.

Case in point: “Cobb,” written and directed by Ron Shelton of “Bull Durham” fame. It’s 1960, and Al Stump (Wuhl), a sportswriter on the rise, is hired to ghostwrite the autobiography of aged and dying baseball legend Ty Cobb (Tommy Lee Jones). Yes, he’s heard the rumors about what a bastard Cobb is. But it’s Ty Cobb. So he drives to Cobb’s home, near Lake Tahoe, buoyant and practically whistling a tune.

Turns out the rumors were off. Cobb isn’t a bastard. He’s a pistol-shooting, morphine-shooting-up, racist, sexist, reckless, abusive and criminally prosecutable bastard.

Pride of the Tigers

Stump keeps realizing this for the first hour of the movie. Let me repeat that: He keeps realizing this. Cobb does crazy shit (shoots his gun at Stump) and Stump looks dumbfounded and says “He’s crazy!” Then Cobb does more crazy shit (drives Stump off a mountain road) and Stump looks dumbfounded and says “He’s crazy!” Here’s where a better actor than Wuhl might have helped, might have given us something more than dumbfounded, but that’s all Wuhl’s got.

Stump keeps realizing this for the first hour of the movie. Let me repeat that: He keeps realizing this. Cobb does crazy shit (shoots his gun at Stump) and Stump looks dumbfounded and says “He’s crazy!” Then Cobb does more crazy shit (drives Stump off a mountain road) and Stump looks dumbfounded and says “He’s crazy!” Here’s where a better actor than Wuhl might have helped, might have given us something more than dumbfounded, but that’s all Wuhl’s got.

Why doesn’t Al Stump just walk away? Does he need the gig that much? Does he need to be near greatness? Could the movie have explored this need? Instead: in this corner, Crazy, in that corner, Dumbfounded. Ding ding.

It gets worse. In Reno, on stage with Louis Prima, Cobb insults blacks, Jews, women and Louis Prima. Meanwhile, Stump has hooked up briefly, and, under the circumstances, tenderly, with cigarette girl/hard-luck case Ramona (Lolita Davidovich, Shelton’s wife), and the two are slow dancing in his hotel room when Cobb, like a vengeful fury, bursts into the room, decks Stump, and literally drags Ramona to his own hotel room, where he forces her to strip at gunpoint and attempts to rape her. “Now you take off them goddamned clothes,” he says. “Get on the bed,” he says. “Lay down and turn around,” he says.

Not exactly “Pride of the Yankees.”

So what do you do if the hero of your story is really a villain? That’s the dilemma for both Al Stump, writing Cobb’s autobiography, and Ron Shelton, writing and directing “Cobb.”

Stump’s solution is to write two books: 1) the hagiography he shows to Cobb but plans to throw away once Cobb dies; and 2) the real book about their experiences together that exposes Cobb for what he is. Question: Could this second book have even been published in1961? “Ball Four,” which blew the lid off of the pretty lies of Major League baseball, is nine years and a cultural tsunami away.

(For the record, the real Al Stump ultimately published two books: the ghostwritten autobiography, “My Life in Baseball: The True Record,” shortly after Cobb’s death in July 1961, and “Cobb: A Biography,” more than 30 years later, in 1994, in which he revealed the less heroic elements of the Georgia Peach. No indication, in the movie, on the 30-year delay.)

Stump’s solution isn’t great but Shelton’s is worse. First, he makes Cobb almost cartoonish in his villainy. In a flashback scene to his playing days, we see Cobb get into a fistfight at every base (at every base), while in present-day 1960 Jones cackles and grins like Mephisto. It makes his performance as Two Face in “Batman Forever” seem subtle.

Against this, Shelton attempts to evoke our sympathy. Ah, Cobb’s got cancer. Ah, Cobb can’t get it up. Ah, Cobb helps out destitute ballplayers like Mickey Cochrane, who later turn their backs on him. Those guys are mean.

Plus Cobb is always right—and Stump is always wrong—about everything. Cobb shoots at a deer with a shaky hand and claims to have hit it in the neck, which Stump denies ... until Stump comes across the dead door in the woods. Cobb says he has final say on his autobiography, which Stump denies ... until he phones his agent and discovers Cobb does have final say. Etc.

Most important, Cobb is honest. “By writing two versions I was becoming what Cobb was not,” Stump says in melancholy voiceover halfway through the film. “I was becoming a liar.” Cobb goes for what he wants—whether it’s that deer in the woods or Ramona in his hotel room—while Stump, poor everyman, equivocates and assumes the best in others. He’s accommodating. And the world shits on an accommodating man. That’s the lesson here. Stump thinks he and his wife, separated for a few months, are working things out, which Cobb laughs at; and sure enough, late in the film, in a cabin in the middle of the night, Stump is served divorce papers. Cobb was right again! So what does Stump do? He pistol-whips the poor bastard serving him. He uses Cobb’s accent and waves Cobb’s gun in the injured man’s face. It’s a worm-turns moment that the movie views positively—or at least comically. See? Accommodating Stump crazy; crazy Cobb counseling caution. Funny.

Awful.

Lies, damned lies, and “Cobb”

The true insult is the “Citizen Kane” analogy. The movie begins with a “New of the World” feature, like “Kane,” and it’s also, like “Kane,” a movie-length attempt at uncovering the childhood secret that explains the man. For Kane, it was “Rosebud,” the symbol of his innocent upbringing. For Cobb, it’s the death of his father, a great man, who is killed by this mother. The father apparently suspected the mother of infidelity and returned early from a business trip to spy on her. The mother apparently suspected the shadowy figure outside her bedroom to be a burglar, or worse, and shot him dead. That’s the story we get from Cobb halfway through “Cobb” but near the end he adds a wrinkle. The father was right. The mother was cheating. And it was her lover, her very naked lover, who shoots the father dead. “The last thing my father saw was the face of the man fucking his wife,” says Cobb in Tommy Lee Jones’ plaintive voice.

The scene takes place at the Cobb mausoleum in a Georgia cemetery. And why are they at this cemetery? It's the place they’re driving by when Stump, after months of abusive behavior from Cobb, finally gets fed up, demands the car stop, and walks out on him. And what sets off Stump after months of abusive behavior from Cobb? Well, Stump has just tried to broker a meeting between Cobb and his estranged daughter, who refuses to see him; then he lies to Cobb, telling him that the woman in the window wasn’t his daughter. Cobb gently calls him on this lie and this sets off Stump. This. Not being shot at. Not being run off the road. This.

A hagiography would’ve felt less like a lie than “Cobb.”

Friday April 01, 2011

Movie Review: “Red Hollywood” (1996)

WARNING: FELLOW SPOILERS

During the inevitable Q&A after a Northwest Film Forum screening of the 1996 documentary, “Red Hollywood,” with one of the two documentarians, Thom Andersen, in attendance, an audience member, perhaps equally inevitably, objected to the documentary’s very existence.

“Red Hollywood” examines the work of those screenwriters and directors who were blacklisted during the late 1940s and early 1950s. These artists, Andersen and Noel Burch contend, are increasingly portrayed as mere victims of the blacklist, when, as Andersen said in his brief introduction to the film, “They had done something .. working within the confines of the Hollywood system.”

That’s what bothered this audience member, a Jewish woman in her sixties. She thought that that something was accusatory; that the doc made a hero out of Joe McCarthy.

That’s what bothered this audience member, a Jewish woman in her sixties. She thought that that something was accusatory; that the doc made a hero out of Joe McCarthy.

“Why would you think that?” Andersen responded matter-of-factly. “What, in the documentary, would make you think that?”

She admitted there was nothing in there per se. Her objection was more of the “Why give ammunition to the opposition?” variety. She asked, “Why make the documentary in the first place?”

Andersen, in his 70s now, with unruly white hair, is a quiet, contemplative, occasionally apologetic man. He thought, viewing the doc again, that parts could’ve been cut. (I agree.) He admitted, yes, maybe they should’ve talked about the anti-Semitic undertones of the blacklist. But in his response to this question, he wasn’t apologetic. Why did he make the doc? He alluded to the last scene we see: Abraham Polonksy reading, charmingly, from his script to “Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here“ (1969), the first film he directed, or got credit for directing, after decades on the blacklist. It’s a scene between the hunted Indian, Willie Boy (Robert Blake), and a woman, Lola (Katherine Ross):

Lola: Willie, are you going to kill them?

Willie Boy: If I have to.

Lola: What do you mean, ”If you have to?“

Willie Boy: I mean if they keep comin'.

Lola: But they‘re white, Willie. They’ll shoot forever.

Willie Boy: How long is that? Less than you think.

Lola: It's crazy, Willie! You can't win. You can't beat them, Willie, ever.

Willie Boy: Maybe... maybe. But they‘ll know I was here.

That’s why he made the doc, Andersen said. So people will know they were there.

Great response.

My response to the woman’s concerns, her fear that the doc was right-wing, was essentially: “You’re kidding.” Because my response to Andersen’s contention that the doc shows the political propaganda of the Hollywood communists is essentially: “That’s it?”

There’s just not much there there.

Sure, we see the upbeat, smiling tractor lessons of “Song of Russia” (1943), co-written by Paul Jarrico, who, in 1950, was named before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), before which he himself refused to testify; but the movie was essentially American war propaganda, since it put our wartime ally in a good light.

Yes, we see “Mission to Moscow” (1943), made at the behest of FDR, and co-written by Howard Koch, who was blacklisted by Red Channels in the 1950s. Koch’s other credits include such communist propaganda as “The Sea Hawk” (1940), “Sergeant York” (1941) and “Casablanca” (1942).

Sure, we get scenes where female factory workers pool their resources to rent one fancy place rather than four crappy ones (“Tender Comrade” (1943), by Dalton Trumbo and Edward Dmytryk, two of the Hollywood 10), and, yes, we get scenes that mock business (“We Who Are Young” (1940), written by Trumbo), or show female independence (“I Can Get It For You Wholesale,” from 1951, co-written by Abraham Polonsky), but there’s nothing inherently communist or socialist about any of it. If anything, the tepidity of these scenes demonstrates how overwhelmingly conservative Hollywood in the studio era was—and, I would argue, remains.

No, the real propaganda, the propaganda so powerful we don’t recognize it as propaganda, isn’t from the left at all. It’s this: love leads to marriage which leads to a happy ending; good and evil are absolute and obvious; and the best way for a lone man to achieve justice, for himself and others, is through the use of violence. These are the main messages we’ve been getting from Hollywood for the past 100 years. They are, for all the attacks on Hollywood from the right, essentially conservative messages.

The bigger problem with “Red Hollywood,” though, is structural. If the intention of the documentarians is to restore artistic integrity to the artists by owning up to their political viewpoints, why not focus on those artists? Give us sections on Lardner, Trumbo, Polonksy, and Lawson. Make it clear which films they worked on, and what, if anything, could be read into these films, and what, if anything, got cut. Give us a sense of their lives in Hollywood. Give us a sense of the strength of the left in 1930s Hollywood, and of the strength of socialism among 1930s Jewish communities, and how anti-Semitic all the 1940s and 1950s red-baiting ultimately was.

Instead, the movie is divided into sections, WAR, CLASS, SEX, HATE, CRIME, which is less illuminating than confusing. It causes us to veer between the early 1930s and early 1950s, vastly different periods in American culture. The writers and directors—who they are and what they believed—are mere afterthoughts in this process.

I like Polonsky and ”Willie Boy“ but I might’ve ended the doc with “Salt of the Earth,” a 1954 film, written, directed and produced by blacklisted artists, which showed, for the first time in any film, a strike from the worker’s point of view. As interesting to me as the film itself, which is available for streaming online, is the critical reaction from Bowsley Crowther, the generally conservative movie reviewer for The New York Times. After delineating the troubled people behind the production, and the troubled production itself, he wrote:

In the light of this agitated history, it is somewhat surprising to find that “Salt of the Earth” is, in substance, simply a strong pro-labor film with a particularly sympathetic interest in the Mexican-Americans with whom it deals ...

The real dramatic crux of the picture is the stern and bitter conflict within the membership of the union. It is the issue of whether the women shall have equality of expression and of strike participation with the men. And it is along this line of contention that Michael Wilson's tautly muscled script develops considerable personal drama, raw emotion and power.

Even let loose outside the studio system, these blacklisted writers, directors and producers, commie bastards all, simply wanted to tell a good story.

Wednesday May 12, 2010

Review: “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves” (1991)

WARNING: WHEN SPOILERS WERE ROTTEN

“Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves” is as uneven as Kevin Costner’s accent within it. It begins gritty and ends in high camp. Robin is heroic, then childish, then heroic again. He assumes leadership of a band of outlaws without being a leader, and he’s actually upstaged in almost every department (dignity, warmth, love) by his right-hand man, Azeem (Morgan Freeman), who demonstrates more leadership in professing to follow Robin Hood than Robin Hood does in professing to lead anyone. Robin can’t even win a swordfight against a high-camp version of the Sheriff of Nottingham (Alan Rickman) without the old knife-from-the-boot trick. Aside from some pretty cool archery skills, one wonders why this guy became the legend. Shouldn’t we be watching the story of Azeem, Thief of Hearts?

“Prince of Thieves” is the third major film version of Robin Hood and it’s interesting to see how it deviates from the Fairbanks and Flynn versions. Most notably, the Crusades were still celebrated in ’22; and though the ’38 version mixed in a strong sense of post-WWI isolationism (get your own house in order, Jack, before traipsing off to foreign lands), the movie is seen from a wholly Christian perspective, beginning with the opening title card:

“Prince of Thieves” is the third major film version of Robin Hood and it’s interesting to see how it deviates from the Fairbanks and Flynn versions. Most notably, the Crusades were still celebrated in ’22; and though the ’38 version mixed in a strong sense of post-WWI isolationism (get your own house in order, Jack, before traipsing off to foreign lands), the movie is seen from a wholly Christian perspective, beginning with the opening title card:

In the year of our Lord 1191 when Richard, the Lion-Heart, set forth to drive the infidels form the Holy Land, he gave the Regency of his Kingdom to his trusted friend, Longchamps...

The language in the ’91 opening title card is less dramatic:

800 years ago, Richard “The Lionheart,” King of England, led the third Great Crusade to reclaim the Holy Land from the Turks. Most of the young English noblemen who flocked to his banner never returned home.

Royalty disappears. In ’22, King Richard and Robin are best friends. In ’38, Richard and Robin fight side-by-side in the third act. By ’91, Richard, now with quotes around “The Lionheart,” is relegated to a last-minute wedding blessing, while Prince John, the main villain in the first versions, is nowhere to be seen. He’s been replaced by the Sheriff of Nottingham, who, in ’22, was a walk-on, and in ’38 was comic relief. Here he actually has his eye on the throne. He also has a name, George, which adds nothing, and a devil-worshipping witch-mother, which adds nothing but weirdness.

Right-hand man? From Little John (’22) to Will Scarlett (’38) to Azeem, the Moor.

Will Scarlett? Turns out he’s Robin’s illegitimate half-brother.

Marian? She’s nearly raped on camera, to comic effect.

The thing’s a mess.

It begins in a Turkish prison in Jerusalem, 1194 A.D., where Holy Crusaders are being tortured and maimed. Robin, with five years hair and beard growth, stoically volunteers himself for a maiming instead of his friend Peter. “This is English courage,” he says with an American accent. Then he breaks himself free, along with Peter, and a nearby Moor, Azeem, who promises to show the way out. In the escape, he loses Peter, brother of Marian, to an arrow, but gains Azeem. “You have saved my life, Christian,” Azeem says. “I must stay with you until I have saved yours. That is my vow.” He says all this with Morgan Freeman’s voice, which makes it even cooler.

We later learn that Robin was a bit of a brat as a child—the Sheriff calls him a “whelp” and Marian tells him: “All I remember of you is a spoiled bully who used to burn my hair”—but his years in prison seem to have changed him. Until he returns to England. Then he seems a child again. He guffaws when he finds out why Azeem was locked up. “Because of a woman? That’s it, isn’t it? That’s it!” A scene later, he sobs into Azeem’s chest when they find the skeleton of Robin’s father strung up in a cage at the remains of Locksley Manor. I suppose the filmmakers wanted character development but, for the viewer, it’s such a sharp contrast to our stoic English prisoner. The unevenness has begun.

Robin quickly makes enemies with Guy of Gisbourne (Michael Wincott), cousin to the Sheriff, and he, Azeem and the blind servant, Duncan (Walter Sparrow), flee into Sherwood Forest. There, across a large stream, he tangles with a band of outlaws, notably John Little (Nick Brimble), and bests him by taking him by surprise. Back at the outlaws’ camp, he suggests fighting back against the powers-that-be. Everyone scoffs but he makes trouble in town, cutting the Sheriff’s cheek, and raising the bounty on his head—a source of pride with him. There’s a nice dynamic here that should’ve been underlined: The more Guy and the Sheriff search for Robin, the more homeless people they create, and the more these people wander into Sherwood and become part of Robin’s army. Will Scarlett (Christian Slater), with a huge chip on his shoulder, blames Robin for their misery, and Azeem counsels against forging an army (“Christian, these are simple people, they are not warriors”), but it all comes together anyway. Arrows are made, people are trained, treehouses are created. Friar Tuck, a bit of a drunkard, is brought aboard and initially clashes with the infidel, until, for the 10th time in the movie, Azeem uses his superior scientific knowledge—this time to help a breach baby get born. Then they’re pals.

The Sheriff, meanwhile, flailing inside his castle, fights back with black arts, treachery, and fierce Celts from the North. After Marian is abducted, Duncan, the blind servant, unknowingly leads the Sheriff and the Celts back to Robin’s hideout. Though Robin’s army handle the first assault, they cannot withstand a barrage of flaming arrows and either flee, die or are captured. The Sheriff then threatens the lives of children to force Marian to wed him—to link him to royal blood so he’ll have an avenue to the throne—and, to honor their wedding day, he plans to hang 10 of the merry men in the town square. Robin, of course, and the few survivors (Azeem, Little John, his wife, Will Scarlett), plan otherwise. But no one’s plan works as planned.

Before the Sheriff goes off to camp.

The Flynn version was not only clean of grit and bad language, it was clean in terms of storytelling: 102 minutes and out. The Costner version, in comparison, rambles and shambles, hesitates and backtracks for either 143 minutes, or an interminable 155 minutes in the extended version, and a lot of this is unnecessary. Did we really need Celts, for example? Did we need the black-arts subplot? I’ll give you Will as Robin’s half-brother, even if it leads to one of the worst line readings in the movie (Robin: I have a brother? I have a brother!); but did we also need to find out the witch was really the Sheriff’s mother? Alan Rickman got raves next to Costner when the movie came out, but he’s so over-the-top he’s really in another movie. He’s in a comedy. Alright I’ll say it: he’s awful. The only thing more awful are some of his lines. When in angry mood: “No more table scraps for the orphans... And call off Christmas!” When visiting his torture chamber: “Sorry to keep you hanging about.” As for the end—when he tries to rape Marian at the altar in front of the Bishop? To what end? Look, he’s a smart-enough guy. His world is crashing all around him, and marrying and impregnating Marian would stop none of the crashing. It’s only there to provide this temporary tension for the audience: Can Robin stop the rape in time? Wow, he does.